The Ecology of Community Networking

Founding Director, 1st-Mile Institute, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Email: rl@1st-mile.org

Telecommunications service providers and government regulators currently refer to the home, office, neighborhoods and communities as the "last mile." They indicate that providing "last mile" enhanced connectivity, especially in rural areas, is not economically viable. They have their economic models backward. The primary source of value in most peoples' lives is local, derived from self, family and community. In a globally networked and communicative society, localities have the opportunity to aggregate and generate new economic value, resources and benefits. The local realm must be considered the "First Mile."

The commonly applied term, "last mile" represents a supply-side driven concept. It is a top-down, national and corporate, technical and engineering perspective on telecommunications infrastructure deployment and services delivery. It is based on legacy hierarchical thinking, intents and actions.

The "First Mile" is based on a demand-side view and understandings. It describes a local geographic orientation for telecommunications infrastructure and services deployment, with a democratic social and economic motivation, that focuses on the difference these systems and services will make in the quality of peoples' lives. The "First Mile" is rooted in realizations about the newly emerging 'hyper-archical' nature of networked economies, local-global relationships, innovation and social change, with the provocative intent that our networked Information Revolution must ultimately be a "people's revolution."

1.0

The development of a techno-mediated, broadband-networked society is complexly upon us. Along with the dominant corporate telecommunications providers, almost all cities, towns and rural regions are considering their broadband related needs and involvements, with many now beginning to deploy enhanced 'first mile' networks.

As a best practice, the way we think about and pursue our network-connected lives should be considered, along with all other aspects of community-building, within a complex, dynamic, whole ecosystems approach so that our network-connected lives may serve as one of the means by which the concepts of sustainable 'community of practice' and 'community of learning' are realized and exemplified.

Unless a community overtly determines that it wants to be un-connected, it will want to plan and deploy a ubiquitous fiber optic and wireless networking infrastructure, with symmetric, high-bandwidth fiber connection to all premises (institutions, businesses, residences), along with high quality mobile devices service coverage. How this is engineered and implemented in detail, will vary widely. Technologies, standards, services and business models are evolving, driven largely by new social and technical understandings, by on-the-ground readiness conditions and by the forces of marketplace 'consumerism.'

Scale is a critical consideration when planning any aspect of a community or a network. Personal networks and neighborhood networks interconnect with city, regional and global networks, being built, operated and provisioned primarily by large telecommunications companies. While 'network neutrality' is now getting a lot of policy and media buzz, we are in actuality experiencing a powerful new wave of corporate media consolidation, the impacts of which are not favorable to the public interest.

Municipalities are beginning to invest in and build 'civic networks,' in part to meet needs not otherwise being met, to reduce spending on network services and to generate potential income. Not all municipalities are capable of, or good at, managing and operating such networks. Those that are, most often already operate other municipal utilities, such as for water or electricity.

Community networks present the opportunity, as with renewable energy, food and agriculture, community banking and other efforts to vitalize localism, to consider alternate economic and organizational models. In this context, two key concepts are important to understand: 'open networks' and 'the commons.'

Open networks are those where fiber infrastructure and radio frequency spectrum are owned by the public sector, or by cooperating public and private sector partners, who offer leased wholesale access and capacity to all providers; as opposed to the current less-than-competitive, proprietary access models. Open networks can offer subscribers greater competitive choice, reduced pricing and devices interoperability, while offering increased income opportunities for services providers.

The commons can be applied to our networked environment in same ways as to watersheds, parks, wild lands, or even neighborhoods. The electromagnetic radio frequency spectrum, while essentially a public, global (universal) commons, like other 'common pool assets,' is currently treated as private property, being auctioned off to highest bidder companies that package and rent use thereof back to us for their shareholders' profit. If, as is increasingly being asserted, access to information is a basic human right, then 'the networked commons' becomes a critical emergent understanding and organizing principle.

In 2009, the Nobel Prize in Physics went to the developer of fiber optics, and the Economics prize was awarded for the first time to a woman, Elinor Ostrom, for her work on economic and governance structures for 'common pool assets.'

Very few 'experts' think about our information environment within an inter-dynamic ecological understanding of matter, energy and information. The field of ecological economics is beginning to extend this fundamental understanding to a re-framing of 'the dismal science'.

A 'new economy' must be based on a recognition and internetworking of many diverse and interdependent economies. The digital internetworking of economic flows and exchanges is going to permeate much of the way the world works and how human societies distribute resources, assign value and acknowledge the complex ecological balance between competition and cooperation. Properly considered, ecological economics takes full account of value: use value, exchange value, and inherent value. Without major changes in our eco-thinking, our best intentioned efforts to build sustainable, networked societies and communities cannot succeed.

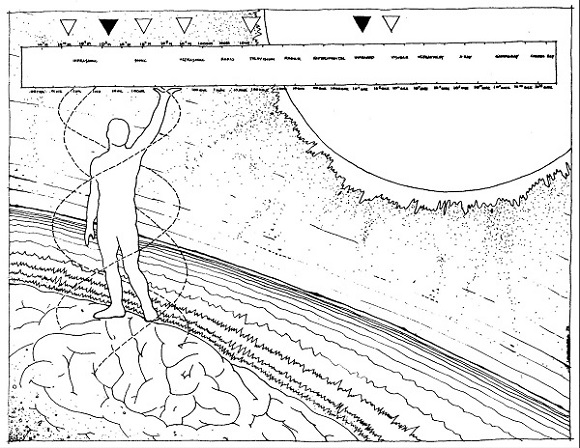

Like all other life forms, we are 'tuning organisms,' entrained to dominant forces and signals that surround, envelop and flow through us. We exist, bathed in a cosmic, life-giving shower of electromagnetic radiation. Over the last century, we have learned to 'ride the waves,' by creating 'techne' to extend our sensing and communicating abilities in evolutionarily transformative ways. As with the harnessing of energy and the development of industrialism, we are generating and consuming everything from valuable resources to harmful waste. In ecological terms, waste in the information environment is both material (rare earth mining, obsolete tech junk, networked warfare) and immaterial (information overload, confusion, deception, speed). Truth, openness and creativity are among the immaterial value-added qualities of information.

The flow of networked information, learning and knowledge, much like water irrigating our fields, is radically transforming all human processes and social constructs, from governance, education, commerce, science, religion, community and family, to the waging of war and peace.

Copper wires, having provided the means of transport of electrons for the last 100 years, are now being replaced by fiber optic lines, which transport photons (light) at high-speed, high-capacity bandwidth. Most wireless systems utilize radio frequency (RF) portions of the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum. New technologies are beginning to utilize frequencies in the visible light spectrum for some wireless communications, potentially lessening RF spectrum congestion, while promoting more energy efficient, dual-use lighting systems (LEDs), and alleviating some growing concerns about possible health effects of RF signals. Such paths are ripe for clean 'green' development.

Today's 'broadband' phase of networked society development is focused largely on technologies, infrastructure, ownership and control. What really matters though is how we use broadband networks, especially to improve the quality of our lives and livelihoods. Vibrant public media initiatives are an important part of growing healthy contemporary communities, augmenting other forms of interpersonal exchange and relationship.

A community network must be community-wide, and should be planned as such. However, few locales have the required leadership, overarching telecommunications master plans, ordinances, land use plans or public works structures in place to guide and benefit them for the coming years.

Ideally, a community network would be a cross-sector organizational partnership among cooperating local entities: government, school districts and higher education institutions, nonprofit organizations, large and small businesses, private sector telecommunications providers and individuals. It could provide: shared local peering, a network operations and data center, leased wholesale broadband network access, qualifying subsidized accounts (via ISP partners), classes and educational outreach, 'pilot projects' initiation and expertise, and could serve as an online front-end, content and applications management system for the community.

Community networks should not necessarily compete with private sector companies to provide commercial services, but should partner with willing telecommunications companies and ISPs to offer local public information services: government, education, libraries, healthcare, culture, economic development and public safety. They could also provide participatory, community-centric content management, appropriate multi-lingual and cultural services, and decision-support tools with mapping, sensing simulation and modeling capabilities, mobile applications, R&D innovation, as well as support services and facilities for online teaching, learning and tele-work.

Financially supporting such efforts will not be easy. However, if properly organized and structured, a community networking initiative can be self-sustaining and may even thrive, its economic life based as much on earned income as on cross-sector cost savings to the community and partners.

Individuals, households, businesses and institutions in a city with a population of about 65,000, currently spend from $50 - $100 million per year on aggregated telecommunications services (phone, cable, wireless, satellite, Internet). Most of this expenditure does not remain local. If only 1% of this total were to be re-allocated and re-invested in well considered and agreed ways, we could meet our networked requirements and desires in a few years time, without need for any additional funds.

Commitment and coordination are critical to all aspects of community building, including first-mile broadband networking. Strategically integrated master planning is a must. Broadband infrastructure deployments should try to be coordinated with new 'smart energy grid' deployments, water systems, transportation, land use and right of ways. Whenever street or road construction or new building projects disturb the ground or do trenching, open conduit should be placed. Cities should institute 'dig once' ordinances, for public safety, to minimize disruptions, and for practical co-location cost effectiveness and savings.

Good planning, coordination and public processes can result in win-win financial outcomes for telecommunications providers and for communities. It can result in improved location and engineering of wireless towers, antennas and coverage areas, while mitigating unwanted impacts. Application of the 'precautionary principle' could result in limiting wireless signals in elementary schools, in setting aside electromagnetic 'quiet zones', or in locating free WiFi coverage areas as a civic amenity.

The path to a networked future requires that we all take greater responsibility for understanding, intentions and actions, while practicing a personal sense of 'information ecology'; not easy, but one of the many grand challenges and socially re-vitalizing opportunities before us.

Democracy (people power) + information + learning = Demosophia (people wisdom).