Whether we look at the use of Twitter in Iran, Moldova or Tunisia, the importance of Facebook in the recent presidential elections in the United States, or the struggles of dissident bloggers in China, we can see how the social movements and other agents of social change are increasingly relying on the new information and communication technologies (ICTs). However, those digital revolutionaries, so often capturing the headlines, are only the most recent example of a trend that has been continuing for millennia.

In this paper I present the results of my recent survey of international social movements in the context of the case studies ranging from centuries past to the events of the last few years. Employing theories of literacy and social movements I will illustrate how the developing ICTs, in a mixture of literate and post-literate ICTs, are perceived by social movement activists, particularly with regards to being empowered by those tools.

Until the mid-20th century, the social sciences paid relatively little attention to the study of literacy, communication technologies and their impact on society. The focus of ongoing research was on the histories of individual technologies - with little attention to their wider implications. First attempts to paint a larger picture were concerned with the modern technologies; hence patterns and trends linked with the historical perspective were not apparent. With sociologists studying the literate, and anthropologists the illiterate, only a few studies looked on the partly literate cultures - even though this was the dominant type of society for the past few millennia. Within the field of sociology this became remedied only in the 1960s, and since then a growing body of studies has contributed to our understanding of those phenomena.1

The theoretical foundations of this research are built on studies of literacy (such as Goody & Watt 1963, Markoff 1986), community informatics (Gurstein 2000, 2007, Williams and Durrance 2008, de Moor 2009), studies of social movements (such as McAdam, McCarthy and Zald 1996, van de Donk et al. 2004, Tilly 2009, Rohlinger 2007), studies on evolution and impact of communication technology and resulting changes of organizational form, (such as Katzman 1974, Eisenstein 1979, Fang 1997, Ling 2004, Yang 2007, Briggs and Burke 2010), theories of sociotechnical change (such as Ackroyd 2005, Bijker 1995 and Weick 1990, van de Donk et al. 2004) and social constructivism (such as Carey 1992, Fang 1997, Furet and Ouzuf 1981, Fulk 1993, Gough 1968, Markus and Robey 1988, Stone 1969, Woolf 1994).

Already in 1981 Graff noted that an attempt at a complete bibliography of only the study of literacy contains over 4000 items; the related but separate fields of communication studies and organizational studies are even larger (Markus and Robey 1988). In such a rich territory, there are many competing scholarly approaches and definitions (Markoff 1986). Markus and Robey (1988) in their overview concluded that "it is no secret that research on information technology and organizational change has produced conflicting results and few reliable generalizations". In order to set a straight course through this maze, we cannot simply define literacy as "the ability to read and write". Already McLuhan in his classic 1962 work differentiated between pre-literate, literate, and post-literate societies, which he distinguished based on their primary mode(s) of communication. As the Internet brings forth an increasing number of post-literate media (podcasts, videocasts, infographics, and so on), even if usually mixed with more traditional textual information, the basic literacy is no longer enough, as the "new literacies" - roughly defined as the ability to use new, mostly digital ICTs - became a necessity of the modern world (Buckingham 1993). Thus, when referring to literacy in modern context, I mean both the traditional and new literacy.

Ackroyd (2005) and Bijker (1995) presented the sociotechnical change theory, which Bijker presented as follows: "Society is not determined by technology, nor is technology determined by society. Both emerge as two sides of the sociotechnical coin during the construction process of artifacts, facts, and relevant social groups". A similar argument is found in Williams and Durrance (2008), who noted that "technology use is directly influenced by social networks, and social networks are directly influenced by technology use". Weick (1990) perhaps most clearly and succinctly presented this logic in saying that technology is both a cause and an effect of many social changes.

According to social constructivist theories of communication in organizations, organization members "share identifiable patterns of meaning and action concerning communication technology" (Fulk 1993). Markus and Robey (1988) in their overview of the relation between information technology and social change stressed that different meanings can be assigned to the same technology, depending on social setting and cultural context. A similar argument can be found in the works of Goody and Watt (1968) who noted that in Tibet literacy was so ingrained in the realm of mystical, religious experience, that it became a goal in itself, with no connection to the mundane world. Its fate was quite different in many other parts of the world, from Europe through Middle East to China, where the skills of reading and writing were increasingly used in the realm of the mundane (Furet and Ozouf 1982, Eisenstein 1979). This has crucial implications, starting with the fact that the same technology can empower both states and anti-state organizations (like certain social movements) as well as communities and individuals.

From the field of social movements, the resource mobilization theory offers valuable insights on how technology is one of the crucial tools for acquisition of resources and mobilization of supporters (McCarthy and Zald 2001). Crucially, as the new ICTs make communication cheaper and more efficient, it becomes much easier for the new challengers to spread their message and take on the established order.

Finally, the most recent contributions to our understanding of how different ICTs can empower communities, facilitating the achievement of their collective goals, comes from the interdisciplinary field of community informatics, which emerged at the turn of the millennium. Research in that field focuses prominently on computerized new media and its empowering use by modern communities aimed at expanding social capital and capacity building (Gurstein 2000, 2007, Williams and Durrance 2008, de Moor 2009). Even with the community informatics focus on new media, as Williams and Durrance note, understanding the historical process that shapes the use of ICTs is important, as the use of the new tools and the resulting empowerment are most successful if they are able to engage with the historical community. As I will show below, this long term historical engagement and resulting growing empowerment can be traced throughout most if not all of our history.

The tools of the revolutionariesDevelopment of more efficient information and communication tools has provided a significant boost to the established actors, such as the state. Yet while governments certainly use such tools to further their social control (Lipsey and Carlaw 2005), they have always been a double-edged sword, as tools of communications increasingly become weapons of social revolutions (Fang 1997). McLuhan in one of his most widely cited statements wrote, "the medium is the message". Some messages are vital, most are not, but the medium itself persists, enabling social change to occur when the conditions (perception of the medium) are right (Fang 1997). Consider the example of writing. It has a significant degree of symbolism; texts were often used to create a psychological impact - both by governments and by the individuals or movements in opposition (Woolf 1994). The writing operates not only as a tool of communication, but also as a symbol with mystical or magical qualities (Woolf 1994, Gough 1968, Fang 1997, Carey 1992). As long as the writing is associated with only a specific group, it empowers that group (empowerment being defined2 as the ability to control the environment around itself, including the behavior of other entities), but once the writing becomes widespread, it encourages rationality and critical thinking among the wider population, making revolutions and social change more likely (Goody & Watt 1963, Stone 1969, Furet and Ouzuf 1981, Markoff 1996, Fang 1997). Bowman and Woolf (1994) have built upon Goody and Watt's (1963) work on the importance of writing for governments, illustrating the significance of the type of medium (the easier it is to use, the harder it is to control).

Despite new tools available to it, the governmental Big Brother's control is far from complete, perhaps because the governments do not adapt as quickly as individuals (Fang 1999). Literacy - which certainly influences people's behavior (Markoff 1986) - is hard to control (Bowman and Woolf 1994). Once the new information technology (a new type of media) spreads, it is next to impossible to put the genie back in the bottle (Woolf 1994, Furet and Ozouf 1982). The dissemination of tools of mass communication has increased the potential for social protest, by increasing the power of the individual to communicate, gather and disseminate information. New tools of communication allow greater anonymity than do public meeting places, encouraging participation (Fang 1997). Information revolutions make people more equal and pave a road to democracy, greater egalitarianism, and sharing of influence and power (Goody 1968, Fang 1997).

It is commonly accepted that writing was first invented and widely used in the Sumerian Empire between 4000 and 3000 BC (Lipsey and Carlaw 2005). It is difficult to discuss with any degree of certainty the changes that took place with the invention of writing, simply because we have no written records from before that time; this is why Goody & Watt (1963) noted that the introduction of writing separates history from prehistory. Nonetheless despite our relative lack of knowledge about the transition from pre-writing to the writing period, there is a consensus among scholars that this event marks a milestone in human history.

Writing was an essential element of the Greek democracy, and thus much of Western culture (Carey 1992, Fang 1997, Innis 1972, Innis and Watson 2007, Goody and Watt 1963). Even before the rise of the true social movements in the late 18th century (Tilly 2009), proto-social movements relied extensively on the media. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where 10% of the population - the nobility (szlachta) - was highly literate, became one of the very few countries in Europe where the absolutist monarchy failed to take root (Wyczanski 1965, Topolski 1994).3

Paper was introduced to Europe around the 12th century. The pace of correspondence and information exchange quickened, a prelude to the printing press revolution (Eisenstein 1979). Printing lowered the costs of distributing decisions made by policymakers (Lipsey and Carlaw 2005). However, in a sign of things to come, it also weakened many of them, from the Roman Catholic Church to the secular leaders (the Protestant Revolt, the end of traditional monarchies). Traditional power holders often opposed the spread of literacy and the printed word: consider examples such as the attempts to limit slave literacy in the US (Robbins 2006), the secret Polish language education in partitioned Poland, an important form of resistance against Russian and Prussian restrictions on Polish education (Lukowski and Zawadzki 2001), or even the implications of the Orwellian Newspeak, the deliberately impoverished language promoted by the state. Literacy facilitated separation of law from the political power, increasing stability and uniformity of law (Lipsey and Carlaw 2005). The leaders could no longer so easily alter the policies and law, now codified, to suit their purposes. The redefining of the relation between the state and the individual, the relation which stresses the rights of the individual and the state's obligation to him, was made possible by the spread of the written culture.

The printed word was at the heart of the religious conflict tearing Europe apart, during the religious wars of the Reformation period or before and during the French Revolution (Furet and Ozouf 1982). Writing broke out of the monasteries and influenced an increasingly secular and rational administration (Gough 1968b, Furet and Ozouf 1982). The printed word was essential in the French revolution (Markoff 1986). Lipsey and Carlaw (2005) write that "the Protestant revolution could not have occurred [...] without the printing press".

Lawrence Stone (as cited in Furet and Ozouf, 1982) notes that the three "Great Revolutions" of modern times - in mid-17th century England, late 18th century France, and early 20th century Russia - all coincided with the moment at which over half of the male adult population became literate. Printing played a significant role in the French and American revolutions, helping to sell their ideas (Darnton and Roche 1989, Furet and Ozouf 1982, Graff 1981, Lockridge 1981). The lower classes were needed for the revolution - and even if (as they often were) illiterate, they could look at posters and listen to others read - and were more easy to organize (Fang 1997, Furet and Ozouf 1982, Markoff 1986). Furet and Ozouf (1982) note that Jacobinism was "an expression of an already-dominant written culture among the masses". By the time Bastille fell in the French Revolution, more than 900 publishers, writers and booksellers had been imprisoned there (Fang 1997).

Newspapers would become a "force for freedom", giving rise to objectivity but also to scandal-mongering and yellow journalism. In the United States, in synergy with growing literacy and the values of the free American nation, the concept of the freedom of the press evolved (Fang 1997). Similar developments occurred in the United Kingdom and much of continental Europe (Popkin 1987, Tilly 2009).

Muckrakers boosted their messages with photos, spearheading many a movement for change (Schneirov 1994, Schudson 2008). Photographs - precursors of the film documentaries - vastly contributed to the establishment of the first US national park in Yellowstone and the child labor legislation of the late 19th century (Fang 1997). In the next century, radio and television replaced print as the delivery mode of information, making individuals more susceptible to emotional messages (Lauer 1997).

The inventions of microphone, radio and movie allowed charismatic leaders to address masses. To some extent Nazism and the atrocities of World War II were a terrible product of technologies that allowed Hitler, the charismatic madman, to captivate millions (Ess 2004).

In many developing countries, television sets and videotapes sent by the government in villages to show propaganda were used to air opposition cassettes. In the Philippines, a video of an assassination of a prominent politician Benigno Aquino was copied, rented, and even mailed by enthusiasts (Ganley 1992). The Soviet Union crumbled alongside its state monopoly on information. Asked what caused the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, Polish president Lech Walesa simply pointed the journalist who was interviewing him to the cameras and microphones pointed at him (Fang 1997). It was the information, unstoppable and spreading, that facilitated the fall of communism throughout Europe in 1989 (Fang 1997). People could hear and see the other side's point of view, could see the gap in wealth that encouraged emigration - but also social changes at home (Fang 1997; Kennedy 1993). Information about one revolution encourages another; for example, Polish Solidarity in 1980s became a model for other revolutions of the Autumn of Nations period (Fang 1997, Kenney 2002). Media was a major factor in the Iranian Revolution (Fang 1997, Teheranian 1979). The recordings of the Tiananmen Square massacre became the haunting ghost for the Chinese government. The Wall Street Journal reported on the Chinese youth two decades ago: "The fax machines are ... a fuel of the revolution. ... They have become the wall posters of this generation..." (Fang 1997).

Social movements learned how to use media, even through sometimes those were painful lessons (Gitlin 2003, Tilly 2009, Kenneth and Caren 2010). Martin Luther King organized demonstrations to gain maximum television coverage; the images of police brutality gained him waves of support in the North (Fang 1999). TV beatified King, Kennedy and the Space Race, and at the same time vilified Nixon, Mao and the Vietnam War. It generated support for conflicts that produced media - such as Chinese opposition after the Tiananmen Square massacre - and led others, such as most conflicts in continental Africa, to be forgotten (Fang 1999) .

In the end, Luther's theses and Mao's little red books, Lenin's pro-communist smuggled writings and anti-communist samizdats, Ayatollah Khomeni's audiotapes and bin Laden's videotapes, Iraqi's blogs and Iranian tweets - they are among the fuels of social movements and revolutionaries. Such fuel that became even more empowering with the arrival of a new technology, the Internet.

The arrival of the Digital Age: the more things change...When we consider how recent the Digital Age that has by now penetrated every aspect of our world is, we have every right to be shocked with its novelty. Darnton (2008) noted that this revolutionary change "took place yesterday, or the day before, depending on how you measure it." An editorial stated that "something that people think of as just another technology is beginning to change our lives, culture, politics, cities, jobs..." (The Economist 2008).

The Internet developed from the military project ARPANET, dating back to 1969; the term was coined in 1974. The World Wide Web as we know it was shaped in the early 1990s, when graphical interface and services like email became popular and reached wider (non-scientific and non-military) audiences and commercial interests. Internet Explorer was first released in 1995. Google was founded barely a decade ago, in 1998. Napster, which greatly popularized digital music, file sharing and digital piracy, was created in 1999, the same year that the free and open source software movement's most popular portal - sourceforge.net - was launched. Windows XP, currently the most popular operating system, was released in 2001. That year saw the birth of Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia - now the largest encyclopedia of the world; the creation of iPod, the most popular player of digital music; and the founding of Creative Commons, both a license and an organization spearheading the free culture movement. Most popular online social networks are even younger - MySpace, for example, dates to 2003, and its main competitor, Facebook, to 2004. Internet telephony began around that time, as the Skype software was released in 2003. Online video, now seen everywhere, has became popular even more recently with the switch from old modems to modern broadband networks. The most popular online video sharing site, YouTube, was founded in 2005. Twitter dates back to only 2006. In 2007 we saw the introduction and quick diffusion of the iPhone smartphone, quickly followed by the Android platform. Wherever we look, the case is clear - Internet is a very recent, emerging phenomenon, likely shaping an entire new generation (Mannheim 1952).

Social-movements.comCharles Tilly defines social movements as a series of contentious performances, displays and campaigns by which ordinary people make collective claims on others. He also defines the movement's repertoire: employment of combinations from among the following forms of political action: creation of special-purpose associations and coalitions, public meetings, solemn processions, vigils, rallies, demonstrations, petition drives, statements to and in public media, and pamphleteering (Tilly 2009). All of those are deeply related to communication tools available to the specific movement.

Ruling classes are more likely to have access the new tools of communication than the underprivileged populace (Fang 1997). But in modern society, the border between ruling classes and the opposition is much less clear. DiMaggio et al. (2001) noted that communication technologies are usually developed in response to the agendas of powerful social actors - and those may include the social movements.4 Further, with the cost of new technologies (cell phones, computers, Internet connection) spiraling down, even individuals, local communities and poor NGOs can quickly put their hands on the equipment rivaling or exceeding what a decade ago was straining budgets of well financed business or governmental organizations (Smith 2001, Buttel and Gould 2004). New inexpensive and effective technologies have given voices to organizations that previously would not have been able to have them due to low resources. A movement, even a transnational one, can be coordinated from the proverbial "teenager's bedroom". Lin (2001) describes the recent case of China's Falun Gong organization, which used the Internet to establish a powerful, hierarchical religious movement under the noses of an authoritarian regime.

It is rarely the social movement that invents or even sponsors the invention of the new communication technologies. Some may be sponsored by the governments (ARPANET...); most are the result of accidental breakthroughs. But they always have unintended consequences, consequences that shake businesses and governments, and are exploited by social movements (Tilly 2009) - just as the printing press was used by the Protestants in 17th century, and by the Polish Solidarity in the 20th.

Schramm (1988) noted, "If it seems far fetched to relate the French and American and British revolutions to the Bible that came off the press in Mainz in 1455, it is less far fetched to relate them to news sheets, newspapers and political traits". Social networks, mobile phones, blogs and podcasts, empowering individuals and local communities, repeat the story of the past, allowing them to chip away at the governments, businesses and even undermine traditional media. They are helped by wikis, videocasts, online petitions, instant messengers, listervs, and other media of the digital age.

The past two decades have witnessed increasing use of the modern technologies - such as the mobile phones and the Internet - by social movements (Buttel and Gould 2004, Denison and Johanson 2007, Smith 2001, Van Laer 2010) and communities (Gurstein 2000, 2007). Their usage gave a new meaning to the term "wisdom of the crowds" - the crowd is certainly better organized if most of its members are fed regularly updated information, gathered by the few individuals deep in the Internet web of information.

How is that possible? Demographics offer a partial answer. We see the influence of the "Net Generation" - the baby boom echo - for whom the web is a life force that empowers their social networks. MySpace, Facebook, Technorati, flickr, Twitter are not the future - for the teenagers and many young adults, they are already here and now. Lenhart and Madden (2005, 2007) presented statistics for mid-2000s that show that more than half of US teens (64%) are content creators: they blog, they edit wikis, they create websites, they post videos and photos. Data from 2005, compared to 2004 data, show that those numbers are on the rise: 57% of teens surveyed a year before were content creators.

As seen in the 2004 US presidential campaign, and even more so in the 2008 one - much of the political discourse takes place online (Trippi 2004, Kohut 2008, Smith and Rainie 2008, Dadas 2008). Consider these numbers: 35% of Americans say they have watched online political videos; 24% - and the number raises to 42% for ages 18-29 - say they regularly learn something about the campaigns from the Internet; and 10% say they have used social networking sites such as Facebook or MySpace to gather information or become involved.

Putnam (2000) described the decay of traditional social networks, but noted that Internet may offer a solution. Indeed, there is evidence that new ICTs are strengthening local communities and organizations (Hampton and Wellman 2003, Hampton 2007, Gurstein 2000, 2007). Tapscott and Williams (2006) speculate that the denizens of the Internet, especially the younger ones, have a very strong sense of common good and collective social and civic responsibility. The Net Generation is accustomed to a world built upon principles of openness - sharing ideas with talented outsiders; peering - moving towards more horizontal organizational forms; and sharing - of intellectual property, stimulating innovation on a worldwide scale. Initially the Internet, like any other tool, shaped itself to the existing customs, but - as happened with all such technologies - it is now shaping its users and creating new customs.

New social movements have arisen on the net. Consider the growth of the Free and Open Source Software Movement (Stallman 2006), the Free Culture Movement (Lessig 2004) or the revitalization of the Open Access Movement, shaking the ivory towers of academia itself (Suber 2009). All of them are concerned with changing the copyright law stifling our economy, culture and science in the aftermath of the Digital Revolution.

DiMaggio et al. (2001) noted that the Internet is much more versatile than tools of the past because "it combines point-to-point and broadcast capability within a single network". It can be any and all of the past communication tools. For decades or centuries, we had capabilities to communicate in various ways with different tools, but the Internet allows one to do all of these things at once. This versatility makes it an excellent tool for social actors who want to influence the world.

Finally, in the ever evolving sea of information, it is doubly interesting to look at one of the newest tools that has just begun to spread throughout the world of the social movements: the wiki (a type of a web page that anybody can edit). Unlike the blogs, which have already attracted increasing attention from scholars (Kahn and Kellner 2004, Dadas 2008), the relation between wikis and the social actors has not been well researched. This can be explained by the fact that wikis are very recent - barely a few years old - and they have only recently begun to spread through organizations. While they are increasingly popular within the Free and Open Source Software sector of the social movement industry, they have only begun to appear within the more traditional social movement organizations, many of which still lack their own wikis. Not all the wikis are run by organizations; many are topic-centered (for example, the Animal Rights Wiki, or the Anti-War Wiki). This is not surprising. As John Seely Brown, former chief scientist of XEROX, noted, a lot of early adopters throughout various organizations "are using wikis without the top management even knowing [about] it" to bypass organizational inertia (Tapscot and Williams 2006).

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, one of the Top 10 most popular sites of the Internet, is a flagship of wiki technology. It has over 8,000,000 registered accounts; some nations' population are only a fraction of that number. Its goal of creating an encyclopedia can be seen as a promise-driven5 type of social movement (Konieczny 2009). Among the ten wikis listed in the "Politics and Activism" section at Wikia - one of the biggest wiki hosting providers - none is connected to a well known social movement organization, and they are all fairly recent. One was started in 2004, two in 2005, six in 2006. With regards to wikis hosted by individual organizations, Indymedia is likely one of the pioneers, dating to June 1999, but most wikis used by social movements are much more recent. The wiki for the Free Culture Movement dates to February 2004; the Social Movements Across Europe wiki was started in May 2006; the New Orleans Wiki (concentrating on recovery and rebuilding) dates to June 2006; the Amnesty International wiki dates from May 2007. At the beginning of that year the Washington Post wrote about Wikileaks, a site that "allows anonymous posts of government documents" (with the stated aim of combating corruption and spreading transparency). Wikileaks' popularity has been steadily growing since then (Alexa 2008). It may appear that traditional social movements are slow to adopt wikis - but new social movements, like ChangeCongress, launched in January 2007, are often built around wikis from their very birth. Without doubt, usage of wikis by social movements is just beginning, but the number of social movements' wikis and their users is growing - as the very knowledge of wiki technology existence and potential spreads beyond the early adopters and among the mainstream activists

Empowering individualsAs organizations challenging the status quo are becoming empowered, so are individuals, inside and outside them. The empowering effect of computer technologies on organizations was seen even in the early days of the Digital Age (Rubinyi 1989, Straub and Werherbe 1989, Mahmood and Mann 1993). Some authors depicted the impact of information technology on organizations as replacing closed, hierarchical, bureaucratic workplace structures with flat networks in which a local initiative takes over the authoritative chain of command, reshaping strategy on a nearly daily basis; unfortunately such claims are too often based on case studies that may not be very generalizable (Tapscott 1999, Tapscott and Williams 2006, 2010).

In 1972 Marshall McLuhan and Barrington Nevitt suggested that with newly developed computer-based communication technology, the consumer would become a producer. Alvin Toffler named this individual a "prosumer". The emergence of the prosumer has transformed many businesses, and change has accelerated in the Internet era (with practices where companies encourage their "prosumers" to write free reviews of their produces, and advertise it to their friends on social networks). Tapscott and Williams (2006) describe this phenomenon as the emergence of the "Wikinomics", a "new art of science of collaboration", best exemplified by the wikis, which for them are much more than just as a type of a collaborative software. They describe them as "a metaphor for a new era of collaboration and participation". Organization of the Wikinomics era is based around the principle that contributing to the commons accelerates growth and innovation.

The argument about ICT potential to empower social actors and influence social changes, however, needs to be tempered with few words of caution. Governments (and businesses) have not given up on trying to adapt the new tools as a means for information control and there is no denying that they have powerful tools of surveillance with which to threaten privacy and freedoms (Lessig 2004, 2006). There are persisting and new social inequalities (from illiteracy to the digital divide) that cannot be ignored. To whatever degree society is being empowered, we cannot forget about underprivileged groups such as the poor and the old that are in danger of being left behind.

In order to test the hypotheses of whether social movements and their activists truly find ICTs empowering, I have carried out a survey of international social movement organizations. As noted by Denison and Johanson (2007), other surveys on the use of ICTs by community organizations exist, but they are usually not international in scope, and primarily focus on managerial issues. The following survey aims to fill in some gaps in our knowledge, as noted in their overview.

For the purpose of this analysis, empowerment has been operationalized as the number of respondents who agreed that a given ICT gives their organization or them more influence. Influence is the term used in the survey itself. Respondents were asked, "does [a particular ICT]" give you more influence"?

A Likert scale was used. Respondents with strong views had their responses weighted as 1, and the remaining respondents, as 0.5. This was used to calculate the perceived value of a given ICT.

The 2009-2010 edition of the International Yearbook of Organizations was employed in this survey as the base of the sampling scheme, providing a list of over 2,000 international social movements.6 The Yearbook has been positively reviewed by scholars (Alger 1997, Modrow 2004). It is seen as a reliable source for research on international organizations, including international social movements, and was used or recommended for such research by Smith and Johnston (2002), Minkoff (2002) and Smith (1997, 2008).

Despite words of praise, it is important to consider how comprehensive and unbiased the Yearbook truly is. In addition to its exclusion of non-international organizations, possible inefficiencies in the Yearbook's information gathering methodology mean that three major potential biases need to be taken into consideration. They can be summarized as follows:

To what degree those biases are a result of delays in Yearbook's publishing cycle and inefficiency in its information flow from developing countries, and to what degree they simply reflect the findings in the literature on the high failure rate in new organizations and their concentration in the developed, English-speaking countries, is nearly impossible to answer without further research.

Upon analysis of the categorization scheme in the Yearbook, the category of organizations concerned with "Societal problems" appeared to be the best fit for the purposes of this study. The organizations listed within it were reviewed, and governmental organizations (as well as the few organizations that appeared to be profit motivated) were excluded. Controlling for duplicate entries, and inactive organizations, in the period the survey was carried out (January-June 2010), the above procedures resulted in a population of 2,619 active social movement organizations (SMO). The entire population was surveyed.

The survey was carried out through email. We do not have any reliable numbers on the worldwide distribution of social movements; nonetheless, existing literature offers some useful indicators. Smith (1997), Smith, Chatfield and Pagnucco (1997) and Smith and West (2005)7 noted that around 80% of the international social movements are based in the developed world. Smith and West (2005) also reported that 75% of the international SMOs have members in the Western Europe and the US, while merely 50% have members in other parts of the world. As it is estimated that in the developed world over 90% of voluntary organizations have access to the Internet (Surman 2000), the results should be representative of that population and not affected significantly by the problem of digital divide.

As of October 30, 2010, 196 out of 2,619 respondents responded to the International Survey, resulting in a response ratio of 7.4% with 6.7% confidence interval at the 95% confidence level.

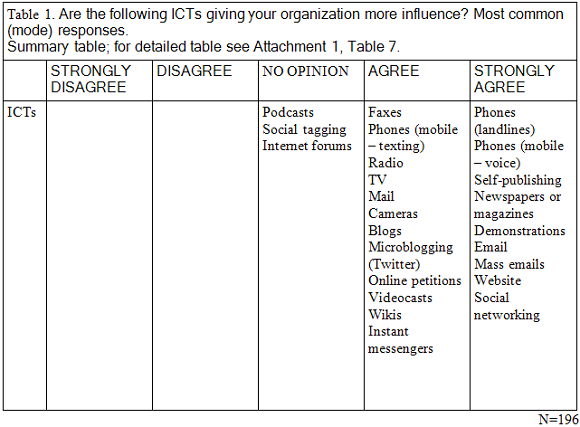

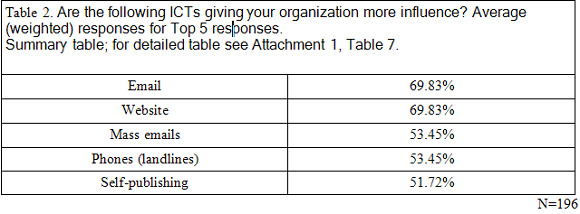

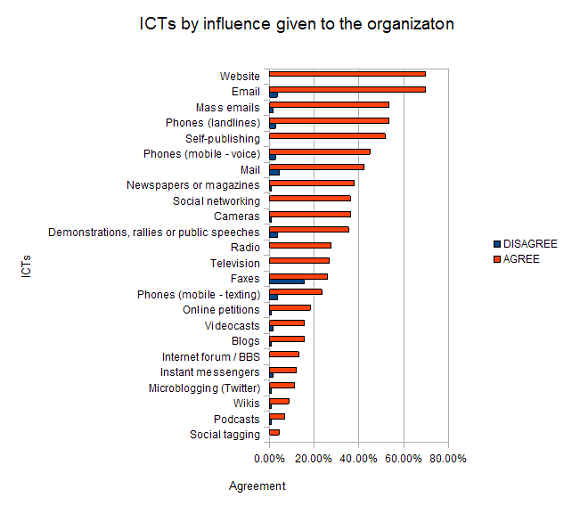

Respondents were asked if the existence of a given ICT provides their organization with more influence. Two ICTs are tied for the most influence given - email and the website. Similarly, two are tied for the 2nd spot - mass emails (discussion lists, listerv) and phones. They are followed by self-publishing, mobile phones, mail, newspapers and magazines, social networking and visual tools (cameras, photos, etc.). Demonstrations and rallies are placed in 11th position. See Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 1 for details.

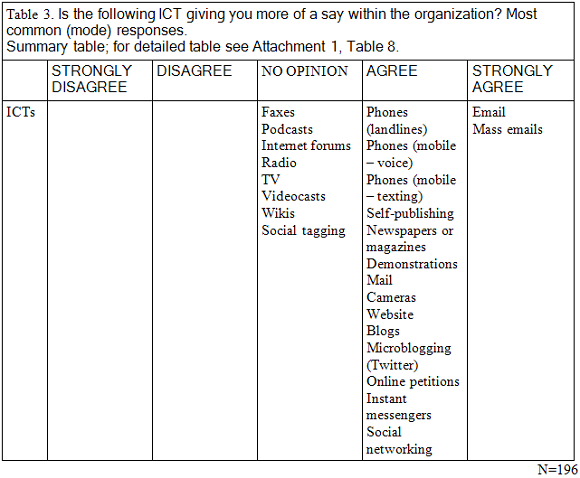

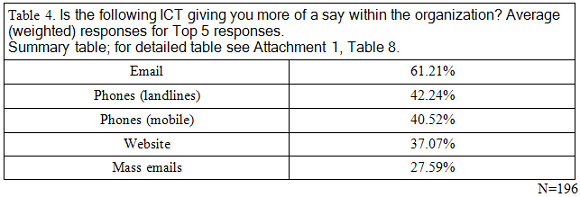

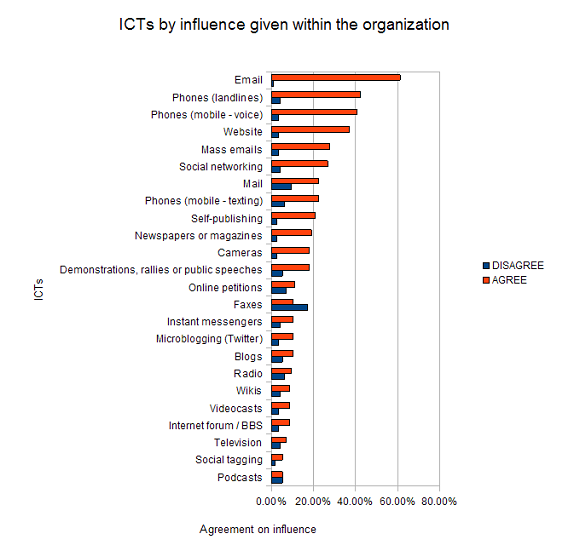

Next, the respondents were asked if a specific ICT gives them more of a say within and outside their organization. Within the organization, email once again takes the lead. It is followed by phones, mass emails, social networking, traditional mail, texting and self-publishing. See Tables 3 and 4 and Figure 2 for details.

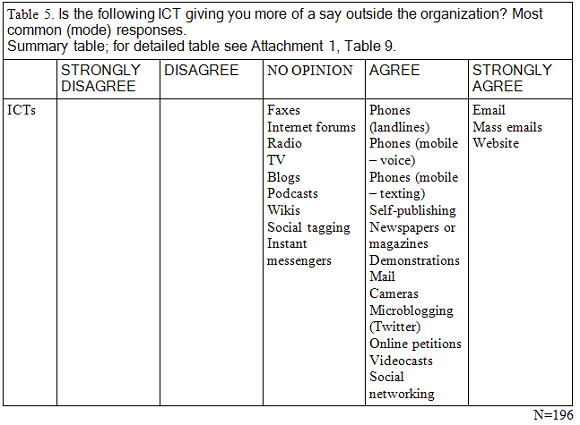

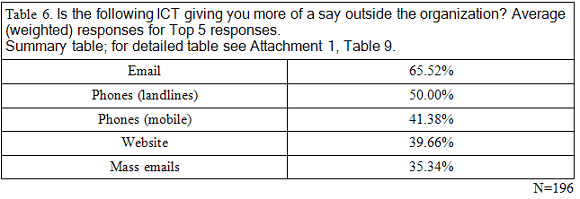

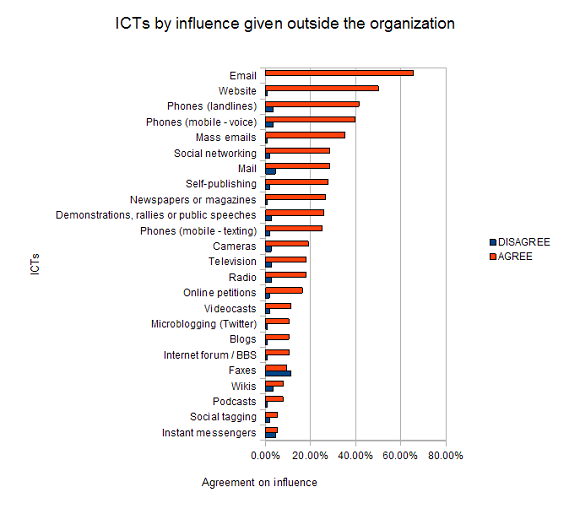

Outside the organization email retains its top position, followed by websites, phones, mass emails, social networking, traditional mail and self-publishing - virtually the same order as within the organization. See Table 5 and 6 and Figure 3 for details.

The respondents perceived the ICTs as highly empowering. An empowerment ratio was calculated, with a weighted score of those finding a given ICT empowering divided by a weighted score of those finding a given ICT not empowering; not a single ICTs scored below 1 with the singular exception of faxes for the use of individuals outside the organization.

The new ICTs (email, websites) are seen as the most empowering; particularly noteworthy is the high position of social networking (a technology less than a decade old), which is listed high not only with regards to empowering individuals outside organizations (6th place), but also as empowering organizations (9th) and individuals within them (6th). Compared to the existing data (see Denison and Johanson 2007), this suggest that Facebook-like social networking is the most important of the new media ICTs to have emerged within the last decade or so.

With the exception of social networking, other Internet-based ICTs of the last decade - blogs, microblogs, wikis, podcasts, videocasts - are not scoring high, even if we control for the number of respondents (fewer respondents use and reply to the question on newer ICTs than on older ICTs). Nonetheless when aggregated empowerment score was calculated, the Internet-based technologies obtained the ratio of empowerment of 16:1, while the non-Internet had the ratio of 14:1. Thus it appears that the Internet-based technologies are seen approximately 15% more empowering than non-Internet based technologies. While this does not lend itself to the argument that the new, Internet era ICTs are spearheading a revolutionary era of empowerment, it fits with existing literature on small to moderate impact of new media (ex. Williams, Wallace and Sligo 2006) and does support a historical argument - that the new media are continuing the trend of increased empowerment through the development of new means of communication.

It is interesting to note the different types of literacy, both old and "new" (Buckingham 1993) needed to deal with the presented ICTs. Both text- and voice-based ICTs are highly ranked. Emails are usually highly textual, but websites and Facebook-like social networks can be much less so, particularly through the use of embedded video and infographics. No single group of ICTs holds primacy, whether we would focus on literate and post-literate division, or on specific mode of communication (text, voice, video). This suggests that what matters to individuals is not so much one (or a group) of specific ICTS; rather, what they perceive as the most empowering, the sheer and growing number of tools they can use to express themselves.

This fits our understanding of social movements' repertoires of contention: they are usually composed of multiple elements, elements that are known to evolve, multiply, or disappear (Tilly 2009). Earl and Kimport (2011) note that while new media can create new effects, they are also often used in a more traditional way, "supersizing" traditional activities. There never was one dominant, "ultimate" communication technology; nor should we expect it to emerge in the future. New ICTs contribute to the empowerment of their users not only because they are more efficient, but also because they add to the pool of options available to the actors. The existence of multiple modes of communication, steadily cheaper, useful in an increasing number of scenarios, and available to an increasingly literate population, is an essential part of the story of the empowerment by ICTs.

Overall, while the individual ranking of the specific ICTs and the rationale behind that order deserves further analysis, the evidence seems sufficient to confirm the hypotheses that both the social movement organizations and their activists find ICTs highly empowering. There is also evidence to suggest that new media are seen as more empowering than the old.

Information and communication technology, in a symbiotic relationship with growing literacy, empowers social actors, including those previously underprivileged, contributing to social change. People seeking change embrace the more effective ways of communication, the receivers are introduced to the medium, embracing it as well and in the end, the media first embraced by the spearheading revolutionaries become commonplace (Lakshmann 1993, Fang 1997). This trend started centuries ago, and continues into the modern day, as social movements - and perhaps all organizations - are increasingly reliant on ICTs and staffed by members of the Net Generation, who cannot imagine the world without the now-popular tools like Twitter, YouTube or Facebook. Those new ICTs do not seem to be ushering an instant revolution, but they are consistently seen as highly empowering, and slightly more than the older ICTs, lending evidence to the claim that throughout known history, proliferation of new ICTs have increased empowerment of individuals and communities.

Although ICT has often been the "necessary" factor in enabling social change, it has never been the "sufficient" factor. ICT can be seen as the enabler, but it does not exist in a social vacuum - instead it is only one of many forces working on a society; this sociotechnical argument should not be mistaken for technological determinism. As Goody (1968) noted, the focus should be on "liberating effects of changes in technology". Development of those technologies does not guarantee change - but when it falls on fertile soil, effects can be rapid and fundamental; in other words, revolutionary. Social revolutions do not require information revolutions, but are often encouraged by them; the relation between information and social revolutions can be seen as symbiotic as each encourages the other (Fang 1997).

Spreading literacy, as historical and present evidence shows, commonly translates to the erosion of traditional paradigms. One may dispute whether growing literacy necessarily translates to the weakening of states (Drezner 2004, Lessig 2006), but as the scholars of community informatics have shown, it has a rather good record in empowering non-state social actors, from individuals to local communities and entire social movements, giving them more rights, more freedoms, and more abilities to influence social change (Lipsey and Carlaw 2005, Fang 1997, Tapscot and Williams 2006). Thus the lesson that one can take from studying historical patterns of growing literacy and development of the new tools of communication is as follows: most social actors, notably including many non-state and non-business actors such as social movement organizations and their activists, value the increased availability and usefulness of ICTs, strongly perceiving them as tools of empowerment.

This research was supported by Research Settlement Fund for the new faculty of Hanyang University.

1 Unlike sociologists, political scientists have paid more attention to the issues of literacy since the 19th century - consider for example the classic works of de Tocqueville (1960). Or the early 20th century works of Michels (1915), who focused more on particular ICTs, and argued that one of the main reasons for his iron law of oligarchy is the inefficiency of available modes of communication, which do not permit a sufficiently large number of people to be able to properly engage in dialogue.

2 For the operationalization of empowerment, see the Methodology chapter.

3 Other interesting cases include Switzerland and the Italian city states - particularly the Republic of Venice.

4 For a real time example, see a list of tools developed by activists for activists at the Global Voices Advocacy Project (http://advocacy.globalvoicesonline.org/projects/)

5 A promise-driven or grievance-creating movement is one that first creates a grievance (like a demand for a "free encyclopedia") and then rides the wave of popular support. This can be contrasted with the more traditional movement approach, where a movement is formed in response to an existing grievance. For more on the difference between those types of movements see Gamson (1990) and for a discussion of the popularity of the promise-driven approach in the new online movements, see Kling (1996).

6 As the Yearbook does not have a category for social movements, the category of organizations concerned with "Societal problems" appeared to be the best fit for the purposes of this study. The organizations listed within it were reviewed, and governmental organizations (as well as the few organizations that appeared to be profit motivated) were excluded.

7 Whose research was based on the Yearbook.

|

Table 7. Are the following ICTs giving your organization more influence? The largest number of responses per row is shaded. |

||||||||||||

|

ICTs |

STRONGLY DISAGREE |

DISAGREE |

NO OPINION |

AGREE |

STRONGLY AGREE |

Respondents (N) |

Respondents (%) |

|||||

|

Phones (landlines) |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

5.17% |

6 |

10.34% |

18 |

31.03% |

22 |

37.93% |

49 |

84.48% |

|

Faxes |

4 |

6.90% |

10 |

17.24% |

8 |

13.79% |

12 |

20.69% |

9 |

15.52% |

43 |

74.14% |

|

Phones (mobile - voice) |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

5.17% |

7 |

12.07% |

16 |

27.59% |

18 |

31.03% |

44 |

75.86% |

|

Phones (mobile - texting) |

1 |

1.72% |

2 |

3.45% |

10 |

17.24% |

15 |

25.86% |

6 |

10.34% |

34 |

58.62% |

|

Self-publishing (of books, booklets, pamphlets, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

4 |

6.90% |

16 |

27.59% |

22 |

37.93% |

42 |

72.41% |

|

Newspapers or magazines |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

3 |

5.17% |

14 |

24.14% |

15 |

25.86% |

33 |

56.90% |

|

Radio |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

6 |

10.34% |

12 |

20.69% |

10 |

17.24% |

28 |

48.28% |

|

Television |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

6 |

10.34% |

11 |

18.97% |

10 |

17.24% |

27 |

46.55% |

|

Demonstrations, rallies or public speeches |

1 |

1.72% |

2 |

3.45% |

4 |

6.90% |

9 |

15.52% |

16 |

27.59% |

32 |

55.17% |

|

Mail (traditional post) |

0 |

0.00% |

5 |

8.62% |

6 |

10.34% |

19 |

32.76% |

15 |

25.86% |

45 |

77.59% |

|

Cameras (taking photos, videos) |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

3 |

5.17% |

16 |

27.59% |

13 |

22.41% |

33 |

56.90% |

|

|

2 |

3.45% |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

11 |

18.97% |

35 |

60.34% |

49 |

84.48% |

|

Mass emails (online newsletters, email discussion groups, listservs) |

1 |

1.72% |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

14 |

24.14% |

24 |

41.38% |

41 |

70.69% |

|

Website |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

13 |

22.41% |

34 |

58.62% |

48 |

82.76% |

|

Online petitions |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

4 |

6.90% |

15 |

25.86% |

3 |

5.17% |

23 |

39.66% |

|

Internet forum / BBS (bulletin board service) |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

13 |

22.41% |

5 |

8.62% |

5 |

8.62% |

23 |

39.66% |

|

Blogs |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

7 |

12.07% |

10 |

17.24% |

4 |

6.90% |

22 |

37.93% |

|

Microblogging (Twitter) |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

5 |

8.62% |

9 |

15.52% |

2 |

3.45% |

17 |

29.31% |

|

Podcasts |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

8 |

13.79% |

4 |

6.90% |

2 |

3.45% |

15 |

25.86% |

|

Videocasts (such as YouTube) |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

5 |

8.62% |

8 |

13.79% |

5 |

8.62% |

20 |

34.48% |

|

Wikis |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

6 |

10.34% |

6 |

10.34% |

2 |

3.45% |

15 |

25.86% |

|

Instant messengers (AIM, MSN, YIM, Google Talk, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

8 |

13.79% |

8 |

13.79% |

3 |

5.17% |

21 |

36.21% |

|

Social networking (MySpace, Facebook, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

6 |

10.34% |

12 |

20.69% |

15 |

25.86% |

33 |

56.90% |

|

Social tagging (Digg, Technocrati, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

7 |

12.07% |

3 |

5.17% |

1 |

1.72% |

11 |

18.97% |

N=58

|

Table 8. Is the following ICT giving you more of a say within the organization? The largest number of responses per row is shaded. |

||||||||||||

|

ICTs |

STRONGLY DISAGREE |

DISAGREE |

NO OPINION |

AGREE |

STRONGLY AGREE |

Respondents (N) |

Respondents (%) |

|||||

|

Phones (landlines) |

1 |

1.72% |

3 |

5.17% |

11 |

18.97% |

17 |

29.31% |

16 |

27.59% |

48 |

82.76% |

|

Faxes |

7 |

12.07% |

6 |

10.34% |

10 |

17.24% |

10 |

17.24% |

1 |

1.72% |

34 |

58.62% |

|

Phones (mobile - voice) |

2 |

3.45% |

0 |

0.00% |

10 |

17.24% |

19 |

32.76% |

14 |

24.14% |

45 |

77.59% |

|

Phones (mobile - texting) |

2 |

3.45% |

3 |

5.17% |

10 |

17.24% |

14 |

24.14% |

6 |

10.34% |

35 |

60.34% |

|

Self-publishing (of books, booklets, pamphlets, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

5.17% |

6 |

10.34% |

18 |

31.03% |

3 |

5.17% |

30 |

51.72% |

|

Newspapers or magazines |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

5.17% |

8 |

13.79% |

10 |

17.24% |

6 |

10.34% |

27 |

46.55% |

|

Radio |

1 |

1.72% |

5 |

8.62% |

7 |

12.07% |

7 |

12.07% |

2 |

3.45% |

22 |

37.93% |

|

Television |

0 |

0.00% |

5 |

8.62% |

7 |

12.07% |

6 |

10.34% |

1 |

1.72% |

19 |

32.76% |

|

Demonstrations, rallies or public speeches |

0 |

0.00% |

6 |

10.34% |

4 |

6.90% |

11 |

18.97% |

5 |

8.62% |

26 |

44.83% |

|

Mail (traditional post) |

2 |

3.45% |

7 |

12.07% |

7 |

12.07% |

14 |

24.14% |

6 |

10.34% |

36 |

62.07% |

|

Cameras (taking photos, videos) |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

5.17% |

6 |

10.34% |

11 |

18.97% |

5 |

8.62% |

25 |

43.10% |

|

|

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

2 |

3.45% |

13 |

22.41% |

29 |

50.00% |

45 |

77.59% |

|

Mass emails (online newsletters, email discussion groups, listservs) |

0 |

0.00% |

4 |

6.90% |

4 |

6.90% |

10 |

17.24% |

11 |

18.97% |

29 |

50.00% |

|

Website |

0 |

0.00% |

4 |

6.90% |

5 |

8.62% |

15 |

25.86% |

14 |

24.14% |

38 |

65.52% |

|

Online petitions |

1 |

1.72% |

6 |

10.34% |

3 |

5.17% |

7 |

12.07% |

3 |

5.17% |

20 |

34.48% |

|

Internet forum / BBS (bulletin board service) |

1 |

1.72% |

2 |

3.45% |

4 |

6.90% |

6 |

10.34% |

2 |

3.45% |

15 |

25.86% |

|

Blogs |

1 |

1.72% |

4 |

6.90% |

4 |

6.90% |

4 |

6.90% |

4 |

6.90% |

17 |

29.31% |

|

Microblogging (Twitter) |

0 |

0.00% |

4 |

6.90% |

3 |

5.17% |

8 |

13.79% |

2 |

3.45% |

17 |

29.31% |

|

Podcasts |

1 |

1.72% |

4 |

6.90% |

5 |

8.62% |

2 |

3.45% |

2 |

3.45% |

14 |

24.14% |

|

Videocasts (such as YouTube) |

0 |

0.00% |

4 |

6.90% |

4 |

6.90% |

4 |

6.90% |

3 |

5.17% |

15 |

25.86% |

|

Wikis |

0 |

0.00% |

5 |

8.62% |

6 |

10.34% |

4 |

6.90% |

3 |

5.17% |

18 |

31.03% |

|

Instant messengers (AIM, MSN, YIM, Google Talk, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

5 |

8.62% |

3 |

5.17% |

6 |

10.34% |

3 |

5.17% |

17 |

29.31% |

|

Social networking (MySpace, Facebook, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

5 |

8.62% |

3 |

5.17% |

11 |

18.97% |

10 |

17.24% |

29 |

50.00% |

|

Social tagging (Digg, Technocrati, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

8 |

13.79% |

2 |

3.45% |

2 |

3.45% |

14 |

24.14% |

N=55

|

Table 9. Is the following ICT giving you more of a say outside the organization? The largest number of responses per row is shaded. |

||||||||||||

|

ICTs |

STRONGLY DISAGREE |

DISAGREE |

NO OPINION |

AGREE |

STRONGLY AGREE |

Respondents (N) |

Respondents (%) |

|||||

|

Phones (landlines) |

1 |

1.72% |

2 |

3.45% |

8 |

13.79% |

20 |

34.48% |

14 |

24.14% |

45 |

77.59% |

|

Faxes |

3 |

5.17% |

7 |

12.07% |

10 |

17.24% |

9 |

15.52% |

1 |

1.72% |

30 |

51.72% |

|

Phones (mobile - voice) |

1 |

1.72% |

2 |

3.45% |

5 |

8.62% |

18 |

31.03% |

14 |

24.14% |

40 |

68.97% |

|

Phones (mobile - texting) |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

6 |

10.34% |

17 |

29.31% |

6 |

10.34% |

31 |

53.45% |

|

Self-publishing (of books, booklets, pamphlets, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

4 |

6.90% |

16 |

27.59% |

8 |

13.79% |

30 |

51.72% |

|

Newspapers or magazines |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

5 |

8.62% |

15 |

25.86% |

8 |

13.79% |

29 |

50.00% |

|

Radio |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

5.17% |

4 |

6.90% |

13 |

22.41% |

4 |

6.90% |

24 |

41.38% |

|

Television |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

5.17% |

3 |

5.17% |

11 |

18.97% |

5 |

8.62% |

22 |

37.93% |

|

Demonstrations, rallies or public speeches |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

5.17% |

5 |

8.62% |

10 |

17.24% |

10 |

17.24% |

28 |

48.28% |

|

Mail (traditional post) |

0 |

0.00% |

5 |

8.62% |

8 |

13.79% |

15 |

25.86% |

9 |

15.52% |

37 |

63.79% |

|

Cameras (taking photos, videos) |

0 |

0.00% |

3 |

5.17% |

6 |

10.34% |

10 |

17.24% |

6 |

10.34% |

25 |

43.10% |

|

|

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

12 |

20.69% |

32 |

55.17% |

45 |

77.59% |

|

Mass emails (online newsletters, email discussion groups, listservs) |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

4 |

6.90% |

11 |

18.97% |

15 |

25.86% |

31 |

53.45% |

|

Website |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

2 |

3.45% |

14 |

24.14% |

22 |

37.93% |

39 |

67.24% |

|

Online petitions |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

5 |

8.62% |

9 |

15.52% |

5 |

8.62% |

21 |

36.21% |

|

Internet forum / BBS (bulletin board service) |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

5 |

8.62% |

6 |

10.34% |

3 |

5.17% |

15 |

25.86% |

|

Blogs |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

7 |

12.07% |

6 |

10.34% |

3 |

5.17% |

17 |

29.31% |

|

Microblogging (Twitter) |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

6 |

10.34% |

8 |

13.79% |

2 |

3.45% |

17 |

29.31% |

|

Podcasts |

0 |

0.00% |

1 |

1.72% |

8 |

13.79% |

3 |

5.17% |

3 |

5.17% |

15 |

25.86% |

|

Videocasts (such as YouTube) |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

5 |

8.62% |

7 |

12.07% |

3 |

5.17% |

17 |

29.31% |

|

Wikis |

0 |

0.00% |

4 |

6.90% |

6 |

10.34% |

5 |

8.62% |

2 |

3.45% |

17 |

29.31% |

|

Instant messengers (AIM, MSN, YIM, Google Talk, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

5 |

8.62% |

6 |

10.34% |

4 |

6.90% |

1 |

1.72% |

16 |

27.59% |

|

Social networking (MySpace, Facebook, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

4 |

6.90% |

13 |

22.41% |

10 |

17.24% |

29 |

50.00% |

|

Social tagging (Digg, Technocrati, etc.) |

0 |

0.00% |

2 |

3.45% |

8 |

13.79% |

2 |

3.45% |

2 |

3.45% |

14 |

24.14% |