Failures and Success in Using Webcasts, Discussion Forums, Twitter, and Email to Engage Older People and Other Stakeholders in Rural Ageing

- Professor, Health Informatics, Faculty of Health, Education & Society, Plymouth University, United Kingdom. Email: ray.jones@plymouth.ac.uk

- Senior Research Fellow, University of Exeter, United Kingdom.

- Professor of Public Health & Ageing, Plymouth University, United Kingdom.

INTRODUCTION

The number of UK households connected to the Internet rose from 61% in 2007 to 77% in 2011 (Office of National Statistics, 2011), and by 2011 the majority (84%) of people in the UK had used the Internet at some point (Office of National Statistics, 2012). But there are 'digital divides' affecting older people in rural areas with 'double impact'. First, although nationally Internet use among older people is starting to 'catch up', still only 61% of those 65 and over, and only 27% of those aged 75 and over, use the Internet, compared to 99% of those aged under 25 (Office of National Statistics, 2012). Older users may lack the confidence to learn Internet skills through trial and error (Ofcom, 2010), unlike their younger counterparts who have grown up surrounded by such technology. Older people may be more susceptible to stop Internet use through personal changes, including physical (e.g. eyesight, hand dexterity, mobility), psychological and cognitive (e.g. confidence, memory), social (e.g. family members moving away), or technology changes (e.g. new versions of familiar things) (Wagner et al., 2010). Second, although Internet use and the demand for acceptable bandwidth in rural areas is high, service providers see worse returns on investment than in urban areas so provision lags behind (Commission for Rural Communities, 2009). In some locations, such as Cornwall, government or European funded initiatives are addressing this (Superfast Cornwall, 2012).

Potentially improving the connectivity, via the Internet, of older people living in rural areas has considerable benefits including communication between isolated communities, access to online services and shopping when these facilities are not available locally, and reduced need to travel large distances. Telecare has been shown effective (Ekeland et al., 2010) and is starting to be delivered at scale (www.kingsfund.org.uk/telehealth).

The New Dynamics of Ageing Programme (www.newdynamics.group.shef.ac.uk) is a seven-year multidisciplinary research initiative supported by five of the UK Research Councils. It funded 35 major projects including 'Sus-IT' (Sustaining IT use by older people to promote autonomy and independence) specifically targeting the uptake of use of Internet by older people (www.newdynamics.group.shef.ac.uk/sus-it.html). The work reported in this paper was from 'workpackage six', one of seven workpackages in the 'Grey and Pleasant Land?' project, an interdisciplinary exploration of the connectivity of older people in rural civic society (www.newdynamics.group.shef.ac.uk/rural-ageing.html).

Many research projects now aim to involve users in planning and implementation throughout the life of the project (Read and Maslin-Prothero, 2011; Barber et al., 2011). The Internet provides the potential for older people in rural areas to discuss issues across the globe, or with support organisations, or with academics. Likewise it provides the potential for support organisations to engage with stakeholders, and for academics to hear from older people.

There are of course now many methods of using the Internet to communicate. The earliest and still most widely used Internet activity amongst older people is email (Madden, 2010). In this study we used email as our primary method of recruitment, so making it an 'entry criterion'. Discussion forums are also widely used. Nimrod et al. (2009) identified more than 40 forums specifically targeting older people, from which they reviewed 14, including four from the UK. All four (www.age-net.co.uk/, www.idf50.co.uk/, www.pensionersforum.co.uk/, www.retiredmagazines.co.uk/) are still operational in 2013. Nimrod et al. did not define 'older' in their paper and we note that the definition of 'older' by these four websites varies considerably (over 40, over 50, pensioners, and over 55 respectively).

Discussion forums have been used extensively as online focus groups (e.g. Adler and Zarchin, 2002; Tates et al., 2009; Stewart and Williams, 2005). Such use is slightly different to long running forums in that members are usually aware that their posts will be used in research, the topics are often introduced by researchers rather than, or in addition to, 'normal' participants, and researchers are concerned about the recruitment and retention of participants. Figures 1 and 2 show anonymised screen shots from the Grey and Pleasant Land Discussion Forums. Participants can log in whenever they want to reply to previous posts or start new 'threads'.

Some (e.g. http://mnav.com/focus-group-center/online-focus-group-htm/) argue that telephone focus groups are much better than online. Online synchronous methods such as videoconferencing have also been used for many years for meetings and these, too, have been used for focus groups (Gratton and O'Donnell, 2011). Videoconferencing has generally required that users have special videoconferencing equipment such as a 'Tandberg', but various methods of live meeting (e.g. 'Wimba', 'Adobe Connect') are now available which do not require expensive equipment to participate but may require the downloading and installation of software (Telepresence and Videconferencing Insight Newsletter, 2012). These approaches are rapidly becoming easier to use and more accessible. Internet video phone calls (e.g. using Skype) between two people are now commonplace and used in interviews (Cater, 2011). These also have the potential for focus groups.

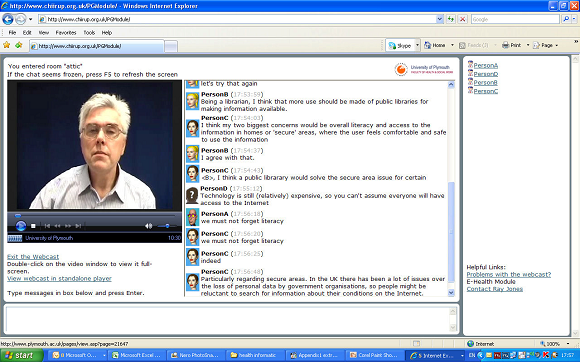

In 2006, we developed a synchronous method, interactive live webcasting (Jones et al., 2006; Maramba and Jones, 2008), that we had used in a variety of ways including with students in online learning (Jones et al., 2009b; Williamson et al., 2009; Doris and Jones, 2009). Figure 3 shows the participants' screen for live webcasting using an anonymised screen from a student discussion. Participants can see and hear the chair or presenter in a 'video window'. The presenter controls the output to the 'video window' and, for example, can fade between talking head or PowerPoint slide. Participants chat by typing into the chat area. Break out rooms can be used to divide the participants up into smaller groups.

Synchronous methods require that participants are available at a certain time. This may be a disadvantage if people are not available but an advantage if by having a scheduled 'event' people put the event into their diaries. The immediacy of response may also provide more 'social presence' (Jones et al., 2009a), but can lead to more 'chaotic' interactions (Graffigna et al., 2008). Adding some audiovisual connection, either one-way (as with webcasting) or two-way (as in videoconferencing), may increase the feeling of social presence but has the disadvantage of being more technically challenging for the participants. Asynchronous methods have the advantage for participants of being able to participate at a time of their choosing and of having time to think of their responses, but the disadvantage that people can 'put it off' and ultimately never participate. If a discussion forum is very 'slow' people wonder if it is still 'live' and whether it is worth contributing (Jones et al., 2011). Most asynchronous methods, however, can be used rapidly, so taking on some of the characteristics of synchronicity. For example, discussion forums and email can be used for immediate responses and so are little different from instant messaging or a typed chat room if the servers are responding quickly.

The rapid rise in the use of social networks such as Facebook and Twitter is well known and they are being increasingly used for qualitative research (Craig, 2011) including focus groups; although there may be problems in their use compared to closed discussion forums (Matt, 2009; Paynter, 2011). Email has been used for one-to-one online interviews, for example, by Cook (2012) and for focus groups (e.g. American Physical Therapy Association, 2012).

However we did not know how best to recruit and engage our different dispersed stakeholders using the Internet. Nor did we know which of the various methods that could be used might be most appropriate. This paper reports an exploration of using the Internet to discuss the findings of the research and wider issues.

Aims

This study asked: Are we able to facilitate inter-regional and inter-sectoral (older people, support organisations, academics) communication on issues concerning older people in rural areas via the Internet? What are the barriers to such communication and can they be overcome? What seems to work?

We have explored the use of webcasting with different forms of interaction, a discussion forum, Twitter, and email listserve in a three phase action research study. This paper describes the failures and ultimate success in using these methods in terms of how well participants have engaged.

Context

This project had a long gestation starting with the formation of a research network in 2005, leading on to a New Dynamics of Ageing 'preparatory network' one year project in 2007-2008 and funding for a full project entitled Grey and Pleasant Land?: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Connectivity of Older People in Rural Civic Society (GaPL) which started in July 2009. Interactive webcasting was piloted with various stakeholders in February 2008 in the preparation of the bid as part of a 'preparatory network'. The GaPL project had seven 'workpackages' (i.e., linked substudies investigating various aspects of older people's inclusion in community life in rural areas) and 27 academics from five UK Universities and another four from Canada in a complementary project. The work described in this paper is based on workpackage six.

The study had three phases. These were not pre-planned but arose from reviews at key points in the overall project of (lack of) progress by the research team with stakeholders. Phase 2 and Phase 3 were attempts to improve the level of participation.

In phases one and two the recruitment of older people to this workpackage was restricted to three rural areas (South West (SW) England, Wales, and Manitoba Canada). SW England is a principal destination of inter-regional migration at retirement, and has the highest life expectancy of all English regions (Champion and Shepherd, 2006). Over a third (36%) of SW residents aged 50 and over live in rural areas and represent a high proportion of the rural population. Rural Wales is experiencing similar demographic trends (Hartwell et al., 2007); 23% of the rural population compared to 19% of the non-rural is above retirement age. Fewer rural residents (67%) than urban dwellers (82%) were born in Wales (Welsh Assembly Government, 2003). Manitoba's rural population comprises a much larger share of the total population than is the case Canada-wide (33% compared to 21%). Compared to urban Manitoba, rural and small town zones have a more polarized age structure, with slightly higher proportions falling within the lowest (children) (in aboriginal areas) and highest (seniors) age categories (in other areas) (Canada Rural Partnership, 2005). People from support organisations were recruited from England, and academics internationally. In phase three we opened recruitment of older people to the world but mainly recruited from England.

Ethics

The proposed study was reviewed and given permission by the University of Plymouth, Faculty of Health, ethics committee (2009).

PHASE ONE METHODS

Initial Invitations to Join This Study

We already had an older person's panel that had taken part in face-to-face discussions with the research team. Some of this panel had also piloted webcasting in the bid preparation. A colleague (SE - see acknowledgements) invited all members of the panel by post. Another colleague (GG) contacted older people known from other projects, both by phone and face-to-face. We emailed all staff members and postgraduate students of the Plymouth University Faculty of Health asking them to forward the email invitation to eligible and possibly interested people in SW England. In Wales, an invitation was sent by a colleague (VB) to all members of the Older People and Ageing Research and Development Network (OPAN) (http://www.opanwales.org.uk/index.htm) recruiting both older people and people in support organisations. Emails were sent to all organisations that were already collaborating on the project and to others identified through personal knowledge or the Internet. Older people in Canada were recruited by email from those participating in studies at the University of Manitoba by another colleague (VM). In addition, international academics were identified by a combination of personal knowledge and Internet searches and contacted by email. Finally, we asked by email all those with whom we had contact through the above process if they had further contacts (snowballing). Eligibility criteria for older people were to be aged 60 or over and living in a rural area (left undefined). We included one person in the Canadian sample aged under 60 but representing older people in her town, and one person in the SW England sample who did not live in a rural area but had many friends and relatives who did.

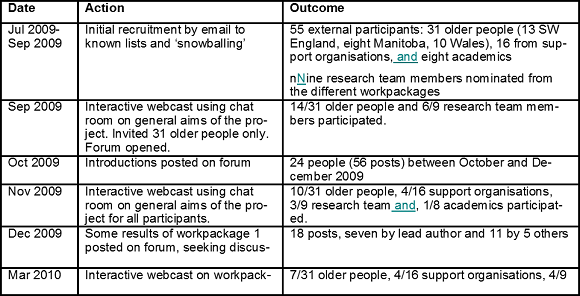

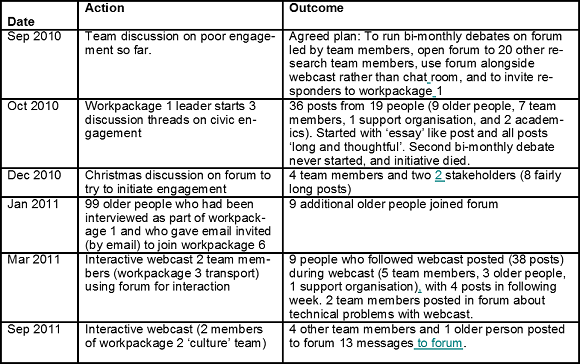

Prompts to Join Webcasts and Discussion Forum

We recruited 55 people: 31 older people (13 SW England, 8 Manitoba, 10 Wales), 16 from support organisations, and eight academics. In September 2009 we set up a discussion forum and ran live interactive webcasts (using a chat room for interaction) in September 2009, November 2009, and March 2010, presented by two of the authors. The aim was to use results from other workpackages from the GaPL project as the basis for discussions, but the first results did not become available until March 2010, so before that date there was little content from the study to discuss. Nine selected research team members representing the other six workpackages were invited to participate in the webcasts and discussion forum between September 2009 and October 2010. Webcasts and discussion forum activity were promoted by emails to participants (Table 1).

PHASE ONE RESULTS

Older People From SW England

Eight of the 13 older people from SW England participated in one or more webcasts, with three people participating in all three. By the end of March 2010, 6/13 people had posted on the discussion forum. Two out of 13 did not participate in either the webcasts or the discussion forum, although one emailed the lead author frequently.

Older People From Wales

Seven out of the 10 older people from Wales participated in one or more webcasts, with two people participating in all three. 5/10 had posted on the discussion forum. Two out of 10 did not participate in either the webcasts or the discussion forum, although both emailed the lead author.

Older People From Manitoba

Three of the eight older people from Manitoba positively withdrew during the year of study, one before ever participating, one after posting one message on the discussion forum, and one after participating in one webcast. Three others never participated. One participated in two webcasts and posted two messages on the discussion forum but none after March 2010. Another participated in two webcasts and posted three messages on the forum, one of which was after March 2010.

People From Support Organisations

Sixteen people were initially recruited from support organisations, of which seven participated in one or more webcasts. Six had posted on the discussion forum by the end of March 2010. However, the number of postings was minimal with one person posting 12 times and the rest posting four times or fewer.

'International Academics'

Of the eight international (non-team-member) academics, one participated in two out of the three webcasts and posted eight times on the discussion forum. Two others posted one or two messages and five never participated.

Research Team

Seven out of nine nominated team members participated in one or more webcasts and three out of nine posted between one and four messages on the discussion forum. Two never participated in either the webcasts or the discussion forum and six out of nine never posted any messages.

PHASE TWO

Team Review

A review of participation to date in the summer of 2010 concluded that there was insufficient involvement of team members and that more structured input may promote more forum discussion around the project findings and related issues on later life in rural areas (Table 2). A plan was agreed to have a bi-monthly debate led by each of the workpackage leads with responses by other workpackage leads to try to draw other stakeholders into discussion. A timetable was set. The forum was also opened to the other 20 research team members. Additionally, we planned to use the forum instead of the chat room as interaction for webcasts so that participants became more familiar with the forum and had fewer 'modalities' to consider.

'Debates'

The slightly more formal debates started in October 2010 generated some interest with 36 posts from 19 people in October. However, the next topic due was never started and the initiative died.

Additional Older People Invited

Ninety-nine people from workpackage one had expressed an interest in further contact with the project and had given email addresses. These were from Cornwall (23), Dorset (6), Dyfed (3), Gloucestershire (23), Monmouthshire (18) and Powys (26). Emails were sent to all 99; 12 were 'undelivered', and 9/87 (10%) that were apparently delivered accepted the invitation to join workpackage six.

Webcasts and Forum Discussions in March and October 2011

These both had relatively little engagement either during the webcasts or subsequently on the discussion forum, with only five stakeholders taking part (despite the addition of nine further older people), in addition to five team members.

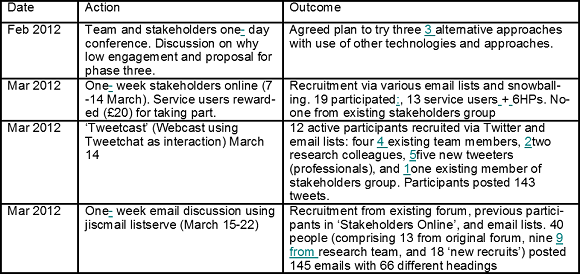

PHASE THREE

Stakeholder Face-to-Face Meeting

At a face-to-face one-day meeting in February 2012 between stakeholders and the research team, the relatively poor engagement so far in workpackage six was discussed (Table 3). The hypothesis was proposed that this limited success was due to four main reasons:

- We had probably started trying to 'engage' too early when there was not enough to talk about. Although with younger age groups, used to being online as a social space, our participants needed a focused activity or discussion topic as a reason to be online. In addition, with older people we know (from emails from friends/partners) that we lost some to illness, frailty or death, so trying to maintain an online discussion over a long period was probably inappropriate. Discussion forums that do not have enough activity soon 'die'. Forums need a critical mass so that, even if asynchronous, people feel that their posts will be read and responded to.

- Although 18/31 older people participated in live webcasts in the initial period and 15/31 in the forum, the technical challenge of live interactive webcasting and use of discussion forums may have been a barrier for some.

- Although more people participated in the live webcasts than the forum we also received emails apologising for 'non-attendance' due to other commitments, among all three groups (older people, support organisations, and academics). So there appeared to be a 'trade off' between the motivation of a 'timed-event' with the difficulty of our stakeholders being able to make the particular date and time.

- The best discussion we had was on transport and practical issues. Some of the other discussion may have been too academic and perhaps lacked sufficient relevance to the concerns of older people.

One Week 'Stakeholders Online' Health Event

In another research project we had been running a series of online one-week events entitled 'Stakeholders online' in which National Health Service (NHS) professionals and service users discussed the implementation of e-health in an anonymous discussion forum with an opening and closing interactive webcast. We started with mental health (Ashurst et al., 2012; Smithson et al., 2012) and then extended the idea to other specialties. We added 'The use of the Internet in Health Services for older people in rural areas' as a topic using the methods of 'stakeholders online'. We advertised via email listserves and recruited six health professionals (mainly from the UK but one from the USA) and 13 NHS service users (of all ages). None of the participants were from the existing GaPL stakeholders group.

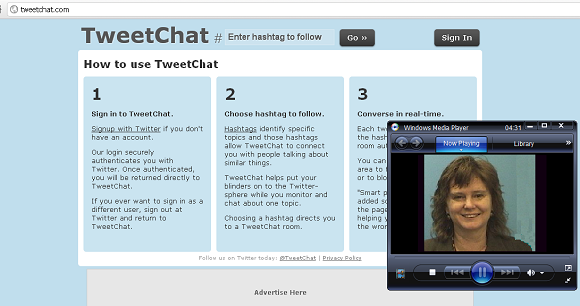

Tweetcast

Twelve participants were recruited by emails to existing stakeholders and team members, and tweets to the followers of the lead author and a colleague (PN). Participants were invited to a live webcast using Twitter with a pre-specified hashtag as the means of communication. Participants were advised to use TweetChat (http://tweetchat.com/) to ensure tweets were linked together and easy to view as a virtual conversation. Although the format of webcast and Tweetchat discussion (Figure 4) worked reasonably well, it did not allow much depth of discussion. Apart from one older person from the original stakeholders group who participated in every event, all new recruits were academics or NHS professionals.

Listserve Discussion

A jiscmail listserve (greyandpleasantland) had been set up in January 2011 as a means of communication for the 31 members of the research team but had been used only infrequently. In March 2012 it was 'repurposed' for a one-week discussion. Eighty-three people were registered to take part in the discussion, and so would have received all messages. These comprised 26 members of the research team, 22 older people, 21 NHS professionals, eight other professionals, three academics and three others. Nearly half (36) were recruited from our 'Stakeholders Online' project; of the 36, four had taken part in the e-health for older people in rural areas discussion the week before. Fifteen were from the original cohort of 55 stakeholders.

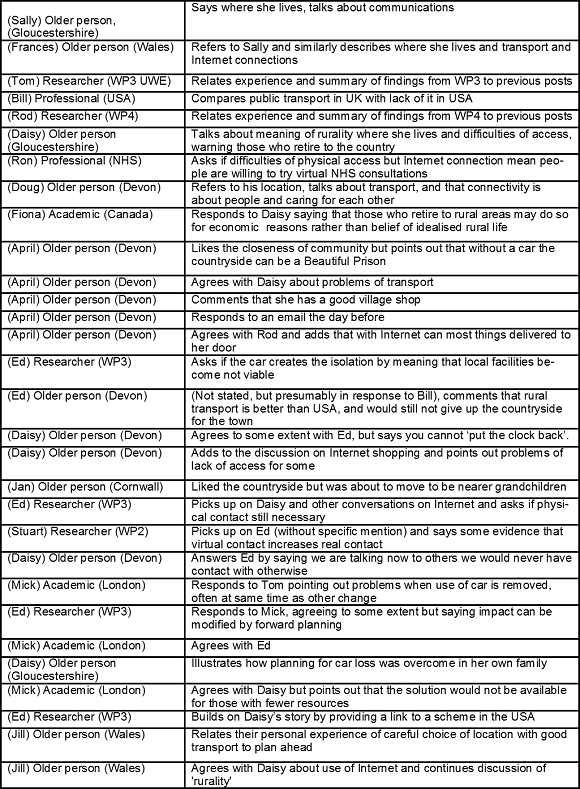

Of the 83, 40 posted one or more emails during the week. Of the 40, 13 were from the original forum, nine were research team members, and 18 were 'new recruits' (mostly from the 'stakeholders online' project). In total, there were 145 emails with 66 different headings. Emails were on average longer than posts on the forum, and much longer than messages on webcasts and Twitter. There were 66 different threads but many posts responded to issues raised from a number of threads. Geographical location and participating group (older person, international academics, research team) were used to frame postings, but participants clearly were able to interact freely across geography and role.

Although there were 66 different email headings, a number of these differed only slightly in punctuation or phraseology and occurred when a participant started a new thread to respond to an email, rather than 'reply'. As all participants were answering to email, rather than accessing in a 'threaded format' on a website, some conversations included a number of email headings. Table 4 gives an example of one thread between 10.42am and 9.24pm on the Thursday of the discussion week. It shows the interaction between regions (e.g. SW England to Wales to USA), and between different sectors (e.g. between researchers and older people). A post from the lead author summarising that day's postings and looking forward to the next day has been omitted. Most of the emails in Table 4 were on two threads ('What is Rural' and 'what is rural?'), but other email headings were included.

Quality Of Posts

The 'quality' of posts in listserve and on the forum were much better than in the Tweetcast. Listserve posts tended to be longer, more reflective and more responsive to other participants than forum posts. This is difficult to demonstrate with simple counts of posts or number of words. In another paper we have used Discourse Analysis to explore how forum members talk about topics of ageing, rural living and technology, and how they describe and display their expectations and preferences for internet use (paper under consideration by Age and Society).

DISCUSSION

Learning From Failures in Phases One and Two to Get Success in Phase Three

Maintaining stakeholders' interest to discuss issues over a long period is difficult and making an 'early start' to recruit a cohort of stakeholders when we did not yet have any results from other parts of the project to discuss was a mistake. There was insufficient 'content' to make the discussion forum 'work'. Although synchronous webcasts, that could be scheduled and provided a focus for discussion, had some success there were also technical barriers for some. Our one-week webcast with forum discussion on e-health lent support to the idea that 'events' worked better than a long undefined period of discussion. It also gave some support to the idea that discussion focussed on more practical concepts, such as the delivery of health services, were more relevant to our audience. The Tweetcast was an interesting experiment that suggested methods of finding new audiences, but, apart from one 'faithful' older person, we only recruited professionals by that means. The technology is probably too new for most of our intended audience. The final 'event', a one-week email discussion using a listserve worked very well. This had removed most of the technical barriers. All participants were familiar with the use of email. No registration or passwords were needed. Messages were received in their accustomed online environment so that participants did not need to remember to log on or do anything special. Although the prior one-week discussion using the webcast and forum discussion had worked fairly well, use of email listserve was clearly better. Currently a time-limited email listserve seems the best solution to engage older stakeholders for an online focus group.

Should We Have Known What Online Technologies To Use Before Starting?

In 2007 the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement commissioned the 'Armchair Involvement' project (Wilson and Casey, 2007) to examine how technologies could be used to engage people across a variety of different sectors including healthcare, and to look at how this might develop in coming years. Wilson and Casey reviewed 24 technologies including digital interactive television, electronic patient record, email, information kiosks, language accessibility tools, mass media, multimedia and web-based decision tools, multimedia messaging, online discussion groups, online surveys and quizzes, picture archiving and communication system, smartphone, social software, telephone, texting, user-generated online content, user-led ratings websites, video conferencing and websites. However, it did not provide any definitive recommendations about alternative online methods such as we have explored in this study.

Developments in Internet Use

The proportion of those who have never used the Internet is decreasing even among older people, partly as cohorts age but also with take up of Internet use amongst older people. In 2008 (Office of National Statistics, 2008) 70% of those aged 65+ had never used the Internet, a decrease from 82% in 2006. By 2012, the percentage that had never used the Internet showed a big difference between those aged 65-74 (39%) with those aged 75+ (73%) (Office of National Statistics, 2012), and combining these 54% of those aged 65+ had never used the Internet. In 2008, the most popular use of the Internet was email, both for older and younger age groups. Although social network use (ever) amongst Internet users grew rapidly among users age 65+ in the USA between 2009 and 2010 (from 13% to 26%), it was still a long way below the 86% of 18-29 year old using social networks in 2010 (Madden, 2010). The use of email by younger people is decreasing as they switch to using Facebook and other social media. On the other hand, in 2010, 55% of Internet users aged 65 and older sent or read email on a typical day compared to only 13% that used social media. This compares with 62% and 60% respectively for 18-29 year olds. Although the use of Twitter is increasing rapidly it is still relatively modest amongst the whole US adult population. Pew Internet (Smith and Brenner, 2012) estimated that in May 2012 15% of all US Internet users and 4% of US Internet users aged 65+ had ever used Twitter.

Our Target Group Of Stakeholders

Rural areas currently have less access to broadband than urban areas (Vicente and Lopez, 2011). Despite the obvious advantages for those living in rural areas, the return on investment in urban areas is much greater for service providers so it follows that broadband is more comprehensively available there (Forman et al., 2005). From the perspective of social learning, people living in cities may also have lower costs to start using the Internet, because they can learn how to use it from their neighbours (Agarwal et al., 2009), and spatial proximity positively influences diffusion of the Internet (Billon et al., 2009). We have no evidence from our data either to support or contradict this claim. Similarly, although we have not found published evidence, it is our impression that many professionals (both academics and service providers) in gerontology seem to be late adopters of technology.

Estimating Future Trends

Will older people in the UK follow the same trends as younger age groups in Internet use? The percentage of those aged 65+ who have never used the Internet has decreased from 70% in 2008 to 54% in 2012. Younger people are tending to stop using email and using Facebook and other social media instead. This may happen in the future amongst older people but we cannot be sure. Hanson (2009) discusses how even when today's 'tech-savvy' younger generations become older, they too will suffer problems in using the Internet. She points to the need to involve older people in the design of systems. But it seems likely that middle-aged Facebook users may become older Facebook users (even if future younger generations have moved on to new forms of communication). So our current recommendation to use email with older cohorts may change over time. It is becoming increasingly clear, however, that we need to consider younger old (65-74) and older old (75+) separately in their technology use.

At a superficial level, Arch (2008) concluded from the literature that older people do much the same online as most other age groups - that is, communication and information searches as well as using online services. Email and children were the primary reasons (Kantner et al., 2003; Morris et al., 2007) why many older people start to learn using computers. They use it for information searches often related to hobbies and interests, travel and holidays, and health (Morris et al., 2007, Dinet et al., 2007). But a more in depth view suggests differences. For example, in 2001, Loges and Jung found that older people have a more restricted range of uses and connect to the Internet from fewer places (2001). Recent Pew statistics show that use of Facebook amongst older people is increasing only a quarter of older Internet users compared to nearly 90% of those under 30 (Madden, 2010). It seems likely that the aim of getting them to 'chat' online in a discussion forum was misguided and that older users need a much stronger formal request to contribute in a structured way, rather than just chat online as younger generations do. Or it may simply be that whatever the age group, our proposed topic of exchanging views about the workpackage results was too vague and not interesting enough.

Fragmentation Of Online Communities

In our study, email-based methods seemed to work best for engagement of participants who had largely been recruited by email. In a study of young people who self-harm we recruited young people from existing discussion forums and they engaged fully in the project discussion forum (Jones et al., 2011). In this study, most who participated in the Twitter trial had been recruited by Twitter. Although some people use several different online modalities with ease, many seem to have a preference for one or maybe two. To get active engagement in online discussion, the method of communication should probably follow the method of recruitment. For example, recruit by email and then communicate by email, recruit on forums and then communicate on forums. Recruiting using one modality and then using another for actual communication may result in less engagement. So while for older people it seems best currently to recruit by email and communicate by email, perhaps for younger people we should recruit by Facebook and communicate by Facebook.

Limitations Of Online Methods In Getting The Views Of Older Stakeholders

We recruited a convenience sample. More than half of those aged 65+ have not used the Internet. Trying to recruit face-to-face was not successful, so our sample only represents those who are online and at least using email. We might expect that typically 6% of all people in the UK aged 65+ may use social media and 22% email on a typical day. Less than 2% have ever used Twitter, so it was not surprising that we recruited only one older person for our Tweetcast, but as Twitter's popularity increases it may be quite a good way of spreading to a wider professional audience.

While younger people may 'hang out' online, this did not seem to be the case for the older people in our study. They tended to go there for a purpose. So scheduling is important. Most older people are not (yet) socialising online. In this study, relatively few participated in the Christmas edition of the forum, contributions were mainly from the research team and came soon after a face-to-face discussion about the difficulties of this workpackage, and may represent a 'sympathy action' by team colleagues.

Limitation Of Our Methods

Our ability to generalise from our findings to others is limited by the pragmatic action research approach in a project lasting three years. Although we claim to have disentangled the reasons for relative failure of engagement to hypothesise and then demonstrate a relatively successful method in phase three, there could have been other reasons for the improvement. These include growing familiarity with the technology, and a feeling that 'at last' there were some substantial project findings to discuss.

CONCLUSIONS

We set out to see if we could facilitate inter-regional and inter-sectoral communication on issues concerning older people in rural areas via the Internet. We have identified barriers to such communication and described the final stage of use of email listserve, which seemed to work best.

RECOMMENDATIONS

We recommend that to involve older people in a long-term online focus group recruitment should be using email and snowball methods. Although 'more connected' participants could be recruited using social media, the method that is most prevalent and will get the most representative and full discussion in 2013 is email. Of course, this still only gives the views of those older people who are online. Recruitment should be just a few weeks in advance of the planned discussion, and each discussion should be time-limited. Trying to maintain exactly the same cohort over projects lasting several years is very difficult. The temptation to be prepared and to recruit far in advance should be resisted. Using a listserve, so that participants are not required to register or log on, will facilitate discussion using their existing technology. A time-limited discussion, with a new topic introduced each day to give some variety, will sustain the discussion; although it may lead to some confusion in that some people may reply to several threads in one email. Participants should be encouraged to correctly title their emails; some probably will not so this confusion is an unavoidable trade off to get some 'rich postings'.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank:

1. All the stakeholders who took part in our

discussions

2. All our colleagues in the Grey and Pleasant Land

project team who have contributed to this part of the

study, in particular:

George Giarchi (GG) who tried to recruit older people

locally in Plymouth face-to--face and via telephone

Nigel Curry (NC) who started the forum debates in October

2010

Graham Parkhurst (GP) and Ian Shergold (IS) who presented

an interactive webcast in March 2011

Yvette Staelens (YS) who presented an interactive webcast

in September 2011

Simon Evans (SE) who contacted the older person's

panel

Vanessa Burholt (VB) who contacted OPAN

Verena Menec (VM) who contacted older people in the

Manitoba region

Norah Keating (NK) who arranged the contact of older

people in Canada with VM

Emily Ashurst who recruited for the one-week

'Stakeholders online' discussion and helped with some

aspects of the analysis

Pam Nelmes (PN) who helped to recruit for and deliver the

March 2012 Tweetcast

Inocencio Maramba (IM) who developed the software for the

discussion forum and the webcast chat rooms

Fraser Reid (FR) who contributed to the original

workpackage proposal

FUNDING

This work was supported by the New Dynamics of Ageing programme grant number RES-353-25-0011.