Let's Get Together: Exploring the Formation of Social Capital in a Malaysian Virtual Community

- Associate Professor of Information Systems, University of Wollongong in Dubai, UAE and Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia. Email: samohdyu09@gmail.com

- Lecturer of Information Systems and Deputy Director of Co-Curriculum, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia. Email: kfaizal@uum.edu.my

INTRODUCTION

Over the years, virtual communities have been growing and gaining popularity in the global context. A virtual or online community is a group of people connected through the internet and other information technologies. The rapid evolution of information and communications technology (ICT) has transformed, networked and bound people into a larger virtual society (Gurstein, 2008).

It was clearly noted that virtual communities have become an important part of modern society and the influence of virtual communities is increasingly pervasive, with activities ranging across various domains - social, educational, political and business. The quest for a better understanding of virtual communities is demonstrated by the proliferation of research conducted by community informatics researchers over the past few years (Gurstein, 2008). Having a strong understanding of community informatics is important as it helps to draw a better picture of the effect of ICT on empowering and enabling community activities (Gurstein, 2007).

Virtual communities built on social network structures began to appear in 2002 and are now among the most popular web-based applications (Finin, Ding, Zhou & Joshi, 2005). According to Chao et al. (2006), many people are interested in participating in virtual discussions to seek solutions for certain problems as well as to share their knowledge with others. Interestingly, some of the web communities, particularly those of professional groups, have brought advantages to their parent organizations.

The rapid growth of ICT provides a new place and new ways for society to meet, collaborate, socialize, and shop (Turoff, 1991; Burnett, 2000). According to Tuuti (2010, p. 4), "this change has been caused by new ways of interacting on the Internet that the so called Web 2.0 has brought with it. Individuals are able to create and publish their own content, follow and comment on others' content and collaboratively organize the vast amount of information available." Such sites allow individuals to publish personal information in a semi-structured form and to define links to other members with whom they have relationships of various kinds.

Recently, an understanding of social capital is becoming recognized as critical and significant, as distinct from the financial, human, intellectual and other types of capital in today's communities. Social capital theory describes the norms, values and behaviors which are shared by a community (Cohen & Prusak, 2001). Those components function as strong glue which binds the members of human networks and communities together and encourages them to cooperate and work together. A community with a good fund of social capital is more likely to easily resolve collective problems and foster individual and community growth (Putnam, 1995).

Existing Community Informatics literature identifies social capital as one of the three important concepts used to understand the intersection between community and technology (William & Durrance, 2008). ICT can play an important role in developing social capital within a community. For instance, Pigg and Crank (2004) conducted a meta-analysis that highlighted ICT capabilities in extending social networks, mobilizing shared resources, and enhancing the bonding and bridging of community. Simpson (2005) stresses the importance of ICTs in helping individuals to effectively participate in community activities which in turn provides better opportunities to strengthen a community's social capital.

However, to what extent ICT (i.e., virtual community) can be used to develop social capital within a virtual setting is still not clear. For example, Pigg and Crank (2004) have clearly noted that understanding the role of ICT in creating social capital is still at a nascent stage and thus requires further research. They further assert that examining the development of social capital using ICT is important as this platform is said to have the ability to contribute to and enhance social networks, provide access to resources, and enhance solidarity in social groups. Hence, in recent years, based on our literature analysis, we found that research has begun to use several theoretical lenses to help explain ICT adoption and usage of social capital concepts although such findings have not been fully supported as yet (Toland, 2012; Matei, 2009; Mignone & Henley, 2009). In line with such studies, to the best of our knowledge, this studyi is the first of its kind to examine the development of social capital within virtual community. In essence, the end goal of this study is to understand the key factors that influence the formation of social capital and to what extent each of the factors matters in the success of a virtual community in Malaysia. A qualitative approach is employed to give an in-depth understanding of the formation of social capital elements in United the Subang Jaya (USJ) E-community.

The rest of this paper is organized into the following sections. The next section explains the background of the study and the section that follows discusses social capital in general, while the third section presents the specific dimensions of social capital employed in this study. The fourth section explains the research methodology. The fifth section presents the research findings and the last section offers some concluding remarks and discusses the study's implications and future research directions.

BACKGROUND OF USJ E-COMMUNITY

The United Subang Jaya (USJ) E-community (www.usj.com.my) was founded on 26 October 1999. This self-funded web community belongs to the residents and ratepayers in the Subang Jaya municipality, Selangor, Malaysia. The USJ E-community has 24,500 registered members and is managed by several volunteers. The volunteers have different backgrounds with respect to race and religion yet work together to acculturate residents in USJ-Subang Jaya and fellow Malaysians and to maximize the benefits of ICT applications at work and at home. The USJ E-community includes a web forum where members can discuss any issues related to the Subang Jaya municipality. This community was awarded "Best Community Website" and "Best Community Development Website" in 2000 by PIKOM and by the My Malaysia Internet Awards. The sample for this study was: 1) USJ E-community core members and 2) USJ E-community members from eight geographic locations (Subang Jaya, Sunway, Puchong, Serdang, Seri Kembangan, Kinrara, and Putra Heights). They were contacted through emails and notices about the research were also advertised on their virtual community site.

CAPITALIZING ON THE SOCIAL ASPECTS

The notion of social capital was first introduced by Lyda Judson Hanifan in her discussions of rural school community centers (Hanifan cited in Smith, 2001). She used the term 'social capital' to describe tangible substances that count for most people in their daily lives. The major concern of rural school community centers was the cultivation of good will, fellowship, sympathy and social intercourse among those that make up a social unit (Hanifan cited in Smith, 2001). Bourdieu (1983) first used the term to refer to the advantages and opportunities accruing to people through membership in certain communities.

With regard to social theory, Coleman (1988) used the term 'social capital' to describe the resources of individuals that emerge from their social ties. Coleman argued that social capital differs from financial and human capital, since social capital inheres in interpersonal relations and describes the durable networks which form social resources among individuals and groups as they strive for mutual recognition (Coleman, 1988). Social capital is part of the necessary infrastructure of civic and community life because it generates 'norms of reciprocity and civic engagement.'

Social capital can be viewed as a common framework for understanding the depth of a community's social connectedness. Putnam (1995) argued that stronger economic growth and effective local and regional government are linked with high levels of social capital. He suggests that social capital refers to features of social organization ? such as networks, norms, and social trust ? which facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit. Social capital is not just the sum of the institutions which underpin a society; it is the glue that holds them together (The World Bank, 1999). Cohen and Prusak (2001) suggest that social capital consists of the stock of active connections among people ? the trust, mutual understanding, and shared values and behaviors which bind the members of human networks and communities together and make cooperative action possible.

Social capital can also be seen as the goodwill that is engendered by the fabric of social relations and which facilitates action (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Social capital at the firm (company) level is created through the connectivity or relatedness between human resources of the firm and the creation of knowledge value, sometimes termed 'Intellectual capital' (Chaminade & Roberts, 2002). Social capital is also used to refer to the network of social relationships. Networks are not merely the result of historical accident; they come about as individuals spend time and energy to connect with others. According to Putnam (1995), social capital represents features of social life such as networks, norms, and trust which enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives.

DIMENSIONS OF SOCIAL CAPITAL

In their comprehensive review of the conceptual literature, Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) divided social capital into three dimensions: structural, cognitive and relational. Structural social capital refers to the ways in which motivated recipients gain access to actors with desired sets of knowledge and intellectual capital. This dimension of social capital is usually studied using a network approach, in which the frequency of contact and resulting social distance among actors in a particular firm or organization are plotted to form a web-like diagram illustrating actor interaction patterns.

In contrast, cognitive social capital recognizes that exchange occurs within a social context which is created and sustained through ongoing relationships (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Similar to the notion of community of practice (Brown & Duguid, 1991) and some aspects of virtual community, cognitive social capital refers to the shared meanings which are created through stories and continual discussions within a specific, often clearly defined, group. These shared meanings are self-reinforcing in that participation in the community is dependent upon an a priori understanding of the context and continual contribution to the on-going dialogues.

The third dimension of social capital deals with the relational aspect, which is concerned with the underlying normative dimensions that guide exchange relationship behaviors. Norms exist when the socially defined right to control an action is held not by the individual actor but by others (Coleman, 1990). Therefore, norms represent degrees of consensus and as such are a powerful although fragile form of social capital (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998).

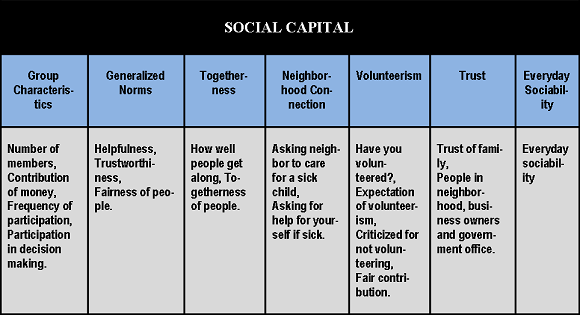

Within a community context, Narayan and Cassidy (2001) stated that social capital comprises seven components: group characteristics, norms, togetherness, sociability, connections, volunteerism and trust. These characteristics are important in any type of community. Table 1A summarizes these social capital components.

For this study, all seven of Narayan and Cassidy's (2001) social capital components are used as our theoretical framework through which to explore and understand the formation of social capital.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

We conducted an exploratory qualitative case study of the USJ virtual community to understand the formation of social capital elements within a Malaysian e-community context. A case study approach is employed for two reasons: (1) the description of a situation can be used to infer some conclusions about the phenomenon under study in a general manner, or (2) the particular case offers something interesting, unique, or new and can provide a detailed understanding of a social process, organization or collective social unit (Myers, 2009; Yin, 2003). The uniqueness in this case lies in the participants chosen for this study, which included all registered members listed on the USJ virtual community website. The interesting aspect about studying this virtual community in depth is that it is one of the most active virtual communities in Malaysia and among the first virtual communities developed in Malaysia.

Participants

Participants were chosen using the snowball sampling technique. Snowball sampling allows the researcher to identify a variety of members in the sample through referrals, where one participant informs the researcher of other potentially good interview subjects capable of offering rich descriptive data. For this study, we contacted key members of the USJ virtual community and asked them to name other members whom they thought would be able to offer in-depth descriptions of the community. These members were then asked to refer other members, based on their longevity of membership or the role they play in the virtual community (e.g. administrators or moderators).

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews and an open-ended online questionnaire were used as data collection techniques. The interview protocol was prepared and designed based on the seven elements of social capital suggested by Narayan and Cassidy (2001); the open-ended online questionnaire used similar questions to those of the interview protocol but its design was adopted from a World Bank-validated questionnaire (Grootaert et al., 2002).

The purpose of employing semi-structured interviews was to generate a set of rich descriptive data from community members, administrators, and moderators. The semi-structured interview technique was chosen for two reasons: 1) it "…provides [a] desirable combination of objectivity and depth and often permits gathering valuable data that could not be successfully obtained by any other approach" (Gall, Borg & Gall, 1996, p. 452); and 2) it allows the researcher to ask probing questions without being constrained by a fixed set of standardized questions (Mason, 2002). The semi-structured interviews were conducted within a fairly open framework, which allowed the researcher to communicate in a conversational yet focused mode. We thus had some flexibility in asking respondents about a general topic and then followed up with more specific in-depth questions. One of the advantages of the interview as a technique is that it allows researchers to probe respondents when their answers are not clear or when a point requires further clarification or justification.

One of the main reasons we employed an open-ended online questionnaire was to give the respondents an alternative way to participate in the study. In this information age, online questionnaires are the most convenient and prevalent method of information gathering for many people. Many respondents preferred this form of communication given the time and space constraints of a personal interview. Some of the advantages that an online questionnaire offers are that it can collect huge amounts of data in a comparatively brief amount of time, and it reduces the need for researchers to manually enter or process the data (Information Technology Services, 2008; Wright, 2005).

Another advantage of online survey research is that "it takes advantage of the ability of the Internet to provide access to groups and individuals who would be difficult, if not impossible, to reach through other channels" (Garton, Haythornthwaite, & Wellman, 1999; Wellman, 1997 cited in Wright 2005, para.7). Data from online questionnaires can also be automatically validated while the respondent is entering it; for instance, if a date is entered in an imprecise format or outside a prescribed range, the online questionnaire can provide an error message asking the respondent to re-enter the date properly and resubmit the questionnaire (Information Technology Services, 2008).

Data Analysis

To analyze the data, this study employed an interpretive/hermeneuticii technique. This method describes a phenomenon through the meanings that people experiencing the phenomenon assign to it rather than those that researchers assign to it. Interpretive research permits the interaction of actor and situation to develop freely (Kaplan & Maxwell, 1994) and attends to three types of data: 1) language (as spoken by actors in the situation or written in literary genres such as state documents or personal diaries); 2) acts and interactions (including nonverbal behavior); and 3) physical objects used in these acts or incorporated into written documents (such as census questionnaires or mission statements). The data are accessed through three methods: 1) observing/participating; 2) interviewing; and 3) reading documents (Yanow, 2003). Using transcriptions of the data, this study took an interpretive approach at the most basic level (the data level), in which we coded for themes within and across the data gathered from the semi-structured interviews and online questionnaires.

Our aim was to analyze the texts obtained from the respondents-both from the open-ended questionnaires and interviews-and from them generate a useful, informative and detailed picture. Since this is a qualitative study, the small number of responses should not be problematic. In addition, the numbers of responses received are inconsistent from one question to another due to either missing data or incomplete responses from the respondents. The main concern of a qualitative study is to offer rich and informative descriptions and discussions of the phenomenon at hand, especially when no other studies have been conducted on it and investigation is therefore only at an exploratory stage.

For that reason, numbers are not as important in a qualitative study because our goal is not to generalize, as it would be with a quantitative study. Instead, the aim of this study is to begin building a preliminary in-depth description of the process of social capital formation in a virtual community. Descriptive statistics were included in the tables for each dimension solely to give the reader a quick overall understanding of the number of respondents in each category. Those numbers are not intended to imply or validate any statements or conclusions. What is most important in our study is what underlies each of the dimensions in terms of the respondents' perceptions and descriptions.

RESEARCH FINDINGS

Demographics of the Respondents

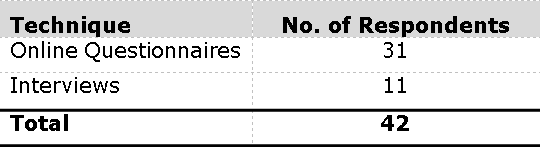

A total of 42 respondents participated in the study. The open-ended online questionnaire had 32 respondents while the semi-structured interviews had 11 respondents (see Table 1).

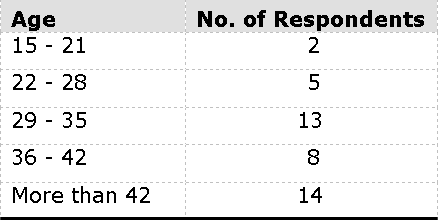

As for the demographics, 28 were male and 14 were female (refer to Table 2). The largest age group was age 42 and above, while the second largest age group was 29 to 35 followed by the group aged 36 to 42.

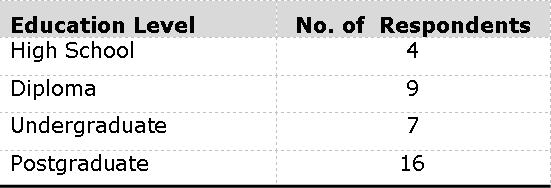

As for the education level of the respondents (refer to Table 3), most respondents' education level was postgraduate, followed by diploma holders and then undergraduate degrees. Six respondents did not disclose their level of education. The occupations of the respondents included executives, managers, doctors, lawyers, academics, computer specialists, engineers, and customer support and service employees.

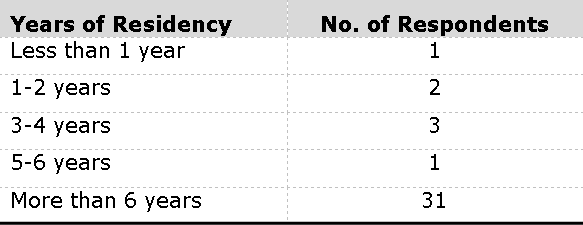

Most of the respondents (n=31) have been living in the USJ community for more than six years, while the others (n=7) have been living there between one and six years (see Table 4). However, four (4) respondents did not disclose their years of residency to the question.

Group Characteristics

The first way to understand the formation process and the factors that contribute to social capital in the USJ virtual community is to examine the group characteristics. In order to look at group characteristics in detail, we asked respondents about the following aspects of their virtual community: 1) participation, 2) leadership, and 3) decision making.

ParticipationTo describe the level and frequency of participation, we first asked respondents what attracted them to this virtual community. Answers fell into three broad classes:

1) Community wellbeing - this category of responses relates to getting to know the community better and having a strong sense of community. Some of the respondents talked about the willingness to help each other in the community, the friendliness of people, getting to know the neighbours and interesting people, and an interest in community development. As illustrated by one respondent:

"the community itself...a bunch of great and diverse people"

2) Obtained information - these responses viewed the community as a channel where members can share and obtain news from their community, their country and the world. The respondents' interests were the latest news and what people were thinking, current political and social issues, and common community concerns. As one respondent mentioned:

"to know what's happening in the community, country and world...to discuss issues"

3) Effective communication -- these responses saw the virtual community as a medium of communication. They could share information with other community members, who could then respond to the information; talk about current happenings in the community; and communicate with friends via chatting. A precise example of this type of response is:

"an avenue to be heard"

We then asked the respondents how frequently they participate in this virtual community. Almost half of the respondents (n=23 of 42, 55%) participated in the virtual community more than once daily, the rest visit the virtual community between once daily and once a week.

Respondents were also asked whether they participate in other virtual communities aside from USJ. A majority of them (n=38 of 42 91%) do visit other websites for these reasons: 1) to obtain information, 2) for social networking, and 3) purely for communication and interaction. Many of the respondents talked about obtaining the latest news, updated information that is not available in the mainstream media and gaining knowledge about other communities. Here is an example quoted from one respondent:

"to gain latest news and what people are thinking"

As for social networking, respondents mentioned reasons such as networking with other virtual communities, getting involved with the activities within a community, and simply for fun. The final reason, communication and interaction, included being able to participate in different discussion forums and interest groups, and getting updated information from other virtual community members.

LeadershipNext, we looked at group characteristics relating to leadership. We asked respondents how new leaders are selected in the virtual community. According to the responses, most of the leaders are appointed by others (n=24 of 42, 58%). Some are selected because they are an owner of the group (30%), and others through an election (12%).

We also wanted to have some idea how leaders make decisions within the USJ virtual community. The results showed that most of the decisions made by the leaders are based on consensus (n=24 of 36, 58%), followed by "gut feelings" or based on intuition (19%), and finally top-down (3%). Three (3) respondents did not response to this question.

Decision MakingWe wanted to know how virtual community members get involved in the decision making process. We classified their answers into four thematic categories: 1) discussion of the issue, 2) consult on the issue, 3) vote, and 4) do not get involved. Many of the respondents talked about getting into a discussion of issues and said that such a discussion could become a constructive debate, but with some rules. The respondents also mentioned that sometimes the discussions can be long so online is better than a face-to-face meeting.

Members of the virtual community also get involved in decision making by being consulted on certain issues. This usually happens with members that are very senior, are knowledgeable or expert in some area or have some experience on an issue. They are consulted when a decision is needed to be made in their area of expertise; for example, someone knowledgeable in construction might be consulted on weighing and selecting the best proposal to build something in the community.

Decision making can also be done by voting. When a decision is split between two good proposals, the leader might ask members to cast their vote. The final option mentioned by some respondents is that they are not invited to participate in the decision making process at all. As one respondent commented:

"Huh?...Decision making?..:)"

We also asked respondents to comment on what the leaders' roles are during decision making in the virtual community. Most of the responses can be categorized into two broad roles: 1) moderator (n=19 of 39, 48%), and 2) administrator (n=15 of 39, 39%). The other five responses indicated no differences in the roles (13%). This is interesting due to the nature of these roles in a virtual environment. Usually a moderator is in control when it comes to discussion forums and mailing lists but an administrator has more control in terms of the overall appearance of the webpage or conduct of the virtual community. One could say that an administrator is a higher ranking officer than the moderator when it comes to the virtual environment. Some of the comments made by the respondents regarding leaders as moderators cited actions such as moderate opinions, moderate the discussions, monitor the threads, solve disagreements and keep order in the forums. As one respondent put it:

" to moderate that opinions and things are done fairly and in accordance to good conduct and governance."

As for comments on leaders as administrators, respondents stressed roles such as preventing misuse, setting rules and regulations, championing a cause or project, weighing the facts and not overruling unilaterally, and bouncing ideas around and crystallizing them later. Here is an example expressed by one respondent:

"express rules and interpret rules and place punishment on those who don't follow the rules."

Generalized Norms

The second component in describing the formation process and the factors that contribute to social capital in a virtual community is generalized norms. Generalized norms are concerned with how members of a community help each other in going about their daily chores and how fairly members of a community treat each other.

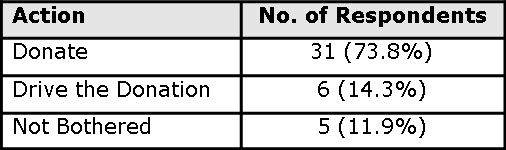

Helpfulness of PeopleFirst, the respondents were asked about giving donations back to the USJ society. The respondents had three options for this question: 1) donate, 2) drive the donation, or 3) not interested to participate in charity work. Many of the respondents (refer to table 5) are willing to donate and if given the chance would be interested in driving (organizing) the donation initiatives. However, a small number of respondents would not be willing to participate in fundraising activities.

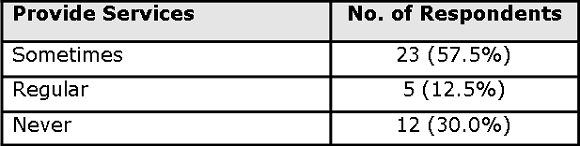

Second, we probed whether respondents were willing to go the extra mile in providing assistance or services to sick, handicapped or elderly people in the virtual community. The result shows that a majority of virtual community members are willing to provide services to less fortunate individuals in the community. Many of them in their lifetime have given once (57.5%; refer to table 6) or regularly (12.5%) to this cause. On the other hand, a number of respondents have never (30%) provided these kinds of help or services to other community members.

Last, we asked respondents what types of help or support they have given to fellow virtual community members (e.g., financial, advice, or other). The results show that a majority of the members have given financial help or support to fellow members (n=19 of 42, 49%). A good number of respondents have also given advice to other members of the virtual community (35%). Other forms of help or support include recommendations or introductions to people who can help, and doing charity, social or community work (16%). Three (3) respondents did not share the types of help or support they received within the community.

Fairness of PeopleFor this category, we wanted to observe how fairly people treat other members of the virtual community. We asked respondents whether there is a lot of prejudice within the virtual community. The majority of the members (n=29 of 39, 74.4%) believe that there is no prejudice within the community, while a small number of members believe that prejudice does exist within the community (25.6%). We further asked respondents who answered "Yes" to this question to give some examples of prejudice within the virtual community. The responses were prejudice against those with different opinions or political inclinations, racism, domination of forums, and censoring of others that do not agree with their views.

We also assessed the issue of members of one race feeling they are being treated fairly by other races during the discussions in the virtual community. The results show that the majority of members feel they have been treated fairly (n=27 of 37, 73%) during their discussions; the rest were divided between "No" (10.8%) and "Not sure" (16.2%).

Togetherness

The third component in understanding the formation process and the factors that contribute to social capital in the virtual community is togetherness. Togetherness is concerned with how well members of a community get along with each other and how close members of a community feel to each other.

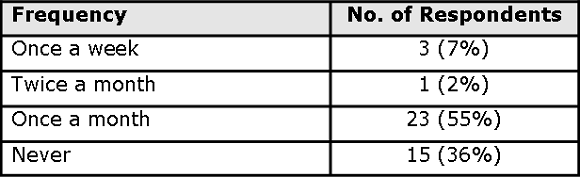

In order to assess how well people get along with each other, we asked respondents to tell us how often they get involved in activities with their virtual community members (refer to table 7). Most of them get involved once a month (55%), followed by a small number that get involved from twice a month to once a week (9%). Quite a number of respondents (36%) never get involved in activities with their friends from the virtual community.

Continuing with the above question, we asked respondents to name some of the activities that they participate in with their fellow community members. The answers varied from dining together, playing games, going to clubs, socializing, donating to charities, helping out in organizing community activities, and working with young people in the community.

Everyday Sociability

The fourth component in illustrating the formation process and the factors that contribute to social capital in a virtual community is through everyday sociability. Everyday sociability refers to how members of a virtual community socialize with each other in their everyday activities.

In this section, we first queried the respondents on how strong their feelings are towards the virtual community. The majority of the respondents have very strong (n=8 of 38, 21%) to strong (45%) feelings towards their virtual community while thirteen (35%) respondents categorized their feelings as average.

We then asked respondents whether other members of the virtual community have visited them at home. A majority of respondents answered "yes" (n=27 of 37, 73%) to the question, with 27% saying "no".

Last, one question asked respondents to name the three most important methods of communication between members of the virtual community. The top three were: 1) forums (39%), 2) e-mail (29.3%), and 3) short message service (SMS)/phone (24.4%). The traditional way of communication which is "visits" to homes of other members seem to be the least important way.

Neighborhood Connections

The fifth component in measuring the formation process and the factors that contribute to social capital in a virtual community is neighborhood connections. Neighborhood connections are concerned with how dependent members of a virtual community are on one another, and how willing they are to help out and build networks with each other.

First, we asked respondents whether they would ask someone in the virtual community for help or advice. Of the 38 responses, 30 (78.9%) answered "Yes" and we then requested examples of the help or advice they had solicited. The answers fell into three broad categories: 1) seeking opinions, 2) needing expert advice or services, and 3) dealing with community or societal issues. The first category, seeking opinions, mostly related to information technology or other technology queries, travel and food advice. Expert advice or services related to wanting or looking for an expert that could handle or solve a specific problem ? for example, the best contractor, the finest gardener, or a trustworthy cleaner. Assistance dealing with community and societal issues related to feedback on life problems or intimate personal issues such as rape or religion.

The "help" responses included help received from a neighbor when the respondent's house was burgled, assistance looking for properties to rent, offering a job to a community member, looking after a house, and help with computer problems.

In terms of advice, the responses included giving out phone numbers for a repairman, providing suggestions/ideas, or offering comfort and assistance to members that are facing a personal problem. Donations included giving to a charity, offering free or discount vouchers, gathering items needed for an orphanage, and raising funds for a certain cause.

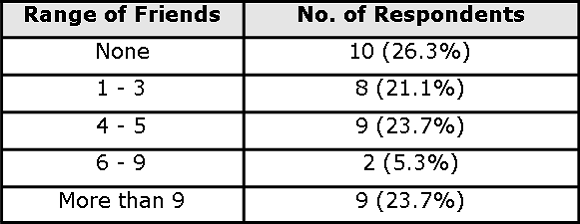

The last question we posed regarding neighborhood connections asked how many close friends the respondents had in the virtual community. The choices were no friends, 1-3 friends, 4-5 friends, 6-9 friends, and more than 9 friends. The results show a wide range of responses (refer to table 8). Ten of 38 respondents (26.3%) do not have any close friends but nine respondents (23.7%) have more than nine friends and nine respondents (23.7%) have 4-5 friends. Overall, 28 of 38 respondents (73.7%) report that they have one more close friends in their virtual community.

Volunteerism

The sixth component in describing the formation process and the factors that contribute to social capital in a virtual community is volunteerism. Volunteerism is concerned with whether members of a virtual community volunteer in activities, what their expectations are during volunteering, and whether there is criticism if one does not volunteer.

In order to see whether volunteerism existed in the virtual community, we asked the respondents whether they were a member of any volunteer organizations and if so which one(s). Most of the respondents volunteer in organizations such the Residents Association, Church Community Service, Neighborhood Watch, Retirement Home, Football Association, Rotary, DesaMentari Project, and Boy's Brigade.

Next we asked the respondents for additional information related to their expectations when volunteering in those organizations listed above. We gave the respondents the choice of the following expectations: 1) improve well-being; 2) make more friends; or 3) other, please specify. The majority of the respondents expected to improve the well-being of the community (n=38 of 42, 90%), followed by expecting to make new friends (7%). Only one respondent specified that they expected to help the unfortunate.

We then asked respondents whether they thought they would be criticized or whether others would have a negative impression of them if they did not participate in any volunteer activities organized by the virtual community. Almost all of the respondents (n=39 of 42, 92%) said that they would not be criticized if they chose not to participate in any volunteer activities.

As a follow up to the question above, we asked the following: if you were given the opportunity to volunteer or organize any activity for the virtual community members, what would it be? Answers included 1) charitable activities, 2) excursion trip, 3) photography outing, 4) family day, 5) protest on certain issues, and 6) kindergarten talent contest.

Trust

The last component in describing the formation process and the factors that contribute to social capital in a virtual community is trust. Trust is concerned with the degree to which members of a virtual community trust each other in their everyday activities.

We examined this component of trust by first asking respondents whether they would announce to their virtual community members if they were to suddenly leave town for a day or two. The options were "yes" or "no". A majority of respondents (n=23 of 36, 63.9%) answered "no," that they would not disclose or announce their whereabouts to other virtual community members.

In addition, we probed respondents as to whether they would let other virtual community members take care of their children. Again they were given the options of "yes", "no" or "never". Many of them answered "no" (n=16 of 35, 45.7%); about 17.1% of the respondents answered "never" (17.1%), indicating that they would not let other members take care of their children. There was however a sizable group of respondents that would let other virtual community members take care of their children (37.1%). Seven (7) respondents did not response to this question.

Next, we inquired about how honest and trustworthy the officials and administrators of the virtual community were perceived to be, and asked respondents to provide examples of their actions. Overall, the major themes respondents focused on were actions taken to suspend users if they crossed the line (by being rude, saying something unkind and by being insulting and threatening) of religion and race, keeping confidential information undisclosed, and initiating fund-raising efforts.

Last but not least, we gathered feedback on what elements of the virtual community could be built up or improved to make it more trustworthy and encourage members to participate. We categorized the answers into three broad themes: 1) getting to know each other, 2) openness and diplomacy about views expressed, and 3) other. For getting to know each other, respondents talked about organizing functions outside the virtual world, more regular face-to-face meetings, having a stronger community spirit, and more social interaction. For openness and diplomacy about views expressed, respondents talked about being more willing to accept opposing views, becoming less egoistic and more understanding, avoiding arguments, and increasing cooperation among members. The "Other" category included having a good relationship with local authorities, and having accurate news and information updated regularly on the virtual community website.

DISCUSSIONS

The main objective of this study was to explore the formation process of social capital in the virtual USJ community. Social capital plays an important role in achieving a comfortable level of community, whether it is virtual or not. Our argument is that, as the use of ICT becomes more and more prevalent in today's work and social life, the virtual communities that are emerging may have roles and social impacts equal to that of any physical community. Hence, the reason we have made the connection between the physical and virtual community is that these two aspects cannot be totally isolated; they are intertwined in their roles in and effects on the success of any community.

In the past, there have been many studies focusing on social capital but not specifically linking social capital and virtual community. Each of those studies has its own perspectives and uniqueness in terms of its methodology, context and variables used. For example, a recent study by Jeffres (2013) aims at understanding how citizens used their communication channels to influence their local government to make decisions. He conducted the study using measures of social capital. One of the insightful findings was that media use such as the Internet as a communication medium has an influence on the civic engagement and actions in urban areas. While Toland (2012) in her research investigated the impacts that ICTs have at the regional level, and the role they play in developing local, regional, and global networks in New Zealand. The findings of this research help us to understand the relationship between the soft networks created by social capital and hard ICT-based networks. Another study conducted by Matei (2009) has investigated the diffusion patterns of encryption and also explored the role played by social capital in shaping such patterns. He applied an integrated theoretical framework developed by Everett Rogers (1962) called 'Diffusion of Innovations' and social capital theory. Interestingly, he concluded that wireless networking is becoming a more prevalent home technology and the key factor that influences adoption of encryption technology in the residential (home) market is based on wealth and strong formal civic capital. Furthermore, related research done by Mignone and Henley (2009) has further examined the bonding, bridging, and linking elements of a social capital framework which involves the Aboriginal peoples in Canada. The focus of this research was to investigate the role of social capital in the successful implementations of ICT in the Aboriginal communities and they found that not only the question of what type of connectivity matters (in terms of the content of the networks), but also how the networks are developed and implemented (in terms of community social capital).

While each of the above studies has examined variations of factors that impact social capital, none of the studies have considered using the seven components of social capital as suggested by Narayan and Cassidy (see Figure 1). In this study we have explored how these seven components are formed in the virtual community of USJ. The following sub-sections discuss our findings surrounding each of the social capital components proposed by Narayan and Cassidy (2001).

Group Characteristics

In the USJ virtual community, we began by examining the first social capital component, group characteristics, in terms of participation, leadership and decision making. These characteristics are important in any type of community. Most people who participate in a virtual community do so because they want to get to know the other community members better. USJ community members are willing to help each other so that the community is better able to promote a sense of belonging between different races in the community. In the long run, the community will be a safer place to live. Cultivating this sense of belonging is very important nowadays because it aligns with the government's 'One Malaysia' initiative.

The USJ virtual community serves as a medium of communication. Community members are able to communicate with each other, make public announcements, meet new friends, bring forward issues pertaining to the community and much more. This is achieved in part by the discussion forum which is moderated by the webmaster. In addition, through this medium, the community members can appoint new leaders for the upcoming annual general meeting. The community can use the discussion forum for nominating new members for the next general meeting, or even for casting their votes which can save time and money. This is how leaders in this community are appointed.

Apart from casting votes and appointing new leaders, the discussion forum is also used for decision-making processes. As we found out, the decision making process in the USJ virtual community may be done by: 1) discussing the issue, 2) consulting on the issue, 3) voting, or in some cases 4) members do not get involved. All these decision making processes are conveniently done online.

Generalized Norms

The second social capital component, generalized norms, is concerned with how willing members of a community are to help each other in going about their daily chores and how fairly members of community treat each other. Our results show that community members are willing to help each other in almost every way, including donations, providing services to the handicapped and elderly people, and also to an extent offering financial help and support.

In terms of how community members treat each other, most respondents seem to feel that everybody respects each other. Only a few respondents felt that some of the members of the community are prejudiced -- for example, towards a certain race or religion. Prejudice and racism do not necessarily occur only between majority and minority groups; there can also be prejudice between subgroups within the majority, or subgroups within the minority. Several factors can play a role in determining whether or not a person is perceived to be prejudiced. For example, older Malaysians remember, or perhaps experienced, the race riots of May 13, 1969 when more than 2000 people lost their lives.

Even today, the younger generation of Malaysia is constantly reminded of the "black" day. With each generation that is born, however, prejudice and racism decreases. Today's community members do not think very much about the color of another person's skin; whereas 30 to 40 years ago, it made a big difference in a person's attitude towards those of a different race (Perlmutter, 2002). Moreover, nowadays people are more likely to form their own opinions and beliefs after being exposed to other cultures in the larger cities.

Togetherness, Sociability and Connections

The third, fourth and fifth social capital components are togetherness, sociability and connections, all of which are concerned with how well members of a community get along with each other, how close members of community feel to each other, how members of a virtual community socialize with each other, how dependent members of virtual community are on each other, and how willing they are to help out and build networks with each other. The common theme that stretches among these three components is that of 'relationships'.

In the USJ virtual community, face-to-face activities are held as frequently as possible, in order to give the community members many opportunities to participate. Activities such as workshops, lectures, discussions, parties, sports and picnics help community members socialize and meet face-to-face, which in turn builds a closer relationship between them. A community can be seen as a web of relationships, requiring all parties to work together in order to create something that is good. But what makes a community work even better are relationships that are positive, co-operative and respectful. In this way everyone works for the good of the whole and towards a common purpose.

Another key to forming effective relationships is to face differences directly. For example, the USJ virtual community includes among its members many different races, religions and opinions. Differences between people are interesting. In a conversation where each person listens to the others, they may each discover a new truth that integrates the two opposing perspectives (Heap, 2001). This is more rewarding than arguing, fighting, or grumbling to someone else. Learning to face differences takes time and can be uncomfortable, but confronting and attempting to understand them is a good exercise and is needed for a harmonious virtual community.

Volunteerism

The sixth social capital component is volunteerism, which is concerned with how often members of a virtual community volunteer in activities, what their expectations during volunteering are, and whether they are criticized if they decide not to volunteer. According to the Fair Labor Standards Act, a volunteer is:

An individual who performs hours of service for a public agency [or organization] for civic, charitable, or humanitarian reasons, without promise, expectation or receipt of compensation for services rendered. (McGruckin, 1998, p.5).

Most of the respondents in this study say that they belong to at least one volunteer organization. Examples of these organizations are Residents' Associations, Church Community Service, Neighborhood Watch, Retirement Home and many more. It is proven that the commitment to the community increases when people volunteer (Ginsburg & Weisband, 2002). Volunteerism is a form of selfless action that promotes community spirit and civic participation while at the same time changing the volunteer's self-concept so as to promote further volunteerism (Omoto & Snyder, 2001). Active volunteers are motivated to do so because they value equitable and rewarding relationships and thus are more likely to continue their services (Pandey, 1979). Therefore, acts of volunteerism are a precondition to promoting and sustaining the loyalty and commitment of a community's members.

Trust

The last component that contributes to the formation process of social capital in a virtual community is trust. Trust is concerned with the degree to which members of a virtual community trust each other in everyday activities. This study found that the USJ virtual community has some trust issues. The community members are still somewhat uncomfortable with their virtual neighbors, reluctant to ask fellow members to look after their kids when they need to do some errands or to tell their neighbors where they are going for a day or two. Some suggestions that respondents believe would help cultivate trust and cooperation among members are more face-to-face meetings, more functions to build community spirit and more social interactions in the physical community.

Putnam (1995) states that trust is the essential component of social capital. He further asserts that trust increases cooperation: the greater the level of trust within the community, the greater the likelihood of cooperation, the end result of which is enhanced trust among members. Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) emphasize that, over time, a culture of cooperation will surface among this trusted group of people which can then be strengthened through social interactions. However, this social relationship can become weak if it is not maintained. Thus, interaction is a precondition for the formation and maintenance of social capital (Bourdieu, 1986).

RESEARCH IMPLICATIONS

This study has several key implications. First, we found that the success of a virtual community rests on several social capital dimensions, including group characteristics, norms, togetherness, sociability, connections, and volunteerism. Therefore, it is evident that people value and enjoy the social relationships they obtain from their engagement in a virtual community. On the other hand, despite the strong sociability aspect, we also found that the formation of trust is still a challenge to develop in the virtual environment. Essentially, people are only enjoying the relationship at a surface level; to go beyond that, the level of trust needs to be enhanced. Based on our understanding of sociability factors, the community needs to formalize some guidelines and recommendations on designing the user interface so that people are more willing to be engaged in more trustworthy/trusting and effective virtual community. In addition, the board of directors of the virtual community could also introduce and develop new rules and policies regarding issues such as ethics, appropriate usage of community forums, and engagement in the virtual community.

Second, it is clear that users have their own preferences in using information technology. Thus, for a virtual community to optimize its sociability aspects, the technologies underlying the virtual community need to be able to accommodate the differing preferences of the members. For example, instead of using purely text-based technology such as email or discussion forums, IS designers could introduce elements such as video streaming (face-to-face) or links to social network sites such as Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn which would allow people to become more comfortable developing personal relationships and friendships as well as professional connections.

Third, the Internet in general offers a new dimension and an unbounded opportunity for business to be conducted locally and globally. More specifically, a virtual community that "lives" on the Internet has numerous implications and applications for businesses and industries that are able to penetrate the virtual community as a new market. A virtual community might find it advantageous to have a 'one-stop-shopping' platform; businesses might seize such an opportunity by offering goods and services via such a platform. Two other implications of this study are that: a) virtual communities can create new business opportunities wherein vendors and retailers can promote and sell goods and services to the virtual community members and b) businesses who take advantage of these opportunities can, in turn, help build, attract, and sustain a new form of virtual community. In short, the virtual communities offer business opportunities, and those business opportunities can also build virtual community.

Finally, community members with a higher level of involvement contribute more value to a virtual community. Our results show that increased community member involvement is likely to enhance the formation of social capital. With higher level of involvement within the community it can promote better sense of community; help share and obtain information about other members within the community; and provide a platform for better communication among members. Besides that, online community administrators should strive to motivate all members to participate in community activities, whether they are individuals who have a long tenure and experience in the community or brand new to the community. The community could do this by organizing and encouraging attendance at periodic face-to-face meetings to introduce participants to one another. These activities will enhance social interactions and build trust.

CONCLUSIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

In conclusion, we found that group characteristics, norms, togetherness, sociability, connections, and volunteerism as important factors that build up social capital among virtual community members in Malaysia. However, trust on the other hand received less empirical supports. Perhaps one of the reasons is that trust as a component of social capital was not examined at an in-depth level by the researchers. It is important to give more emphasis on measuring the role of trust as it can help understand its impact in the development of social capital within online community context. There is no doubt that social capital is an important resource for the long-term survival of virtual communities because social capital helps members become more tolerant, less skeptical, and more sympathetic in their social relationships. Last but not least, social capital provides vast opportunities for community members to resolve collective problems more easily. Therefore, by each member doing his or her part, the community could advance more smoothly, particularly when the members are bonded by close relationships. As a consequence, such relationships will contribute to building a more effective virtual community. This finding is strongly supported by a recent study conducted by Burmeister (2012) who found that one of the most significant values for a senior citizen targeted virtual community to exist is a high sense of belonging to a community of peers.

For future investigation, we suggest that the research should be broken down into different stages, each of which would examine a group of two to three variables. For example, one study might look at the variables of 'trust' and 'togetherness' and attempt to describe in detail the role of trust and togetherness in the formation of social capital in a virtual community. Another study might examine how social capital is formed and what role it plays in other forms of virtual communities such as an online gaming community, especially how players build trust between each other in a very competitive virtual environment. Another area which could be explored would be to investigate how bloggers build social capital in cyberspace through their writing and commentaries.

REFERENCES

i This study was sponsored by the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) of Malaysia under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (Grant no. 11700).

ii The word hermeneutic, meaning interpretive, is a branch of philosophy concerned with human understanding and the interpretation of written texts. The word derives from the Greek Hermes in his role as patron of communication and human understanding.