Communities in Context: Towards Taking Control of Their Tools in Common(s)i

Owner, CommunitySense, Tilburg, the Netherlands.

E-mail:

ademoor@communitysense.nl

Introduction

Communities revolve around shared interests, norms, and identity. It generally takes time to become admitted and fully accepted and acknowledged as a community member. Building common identity and bonds between community members are typically a primary focus for the design of online communities (Ren et al, 2007). Much research and development on communities and their technologies therefore focuses on intra-community aspects: the community lifecycle; community governance and management issues such as facilitation and conflict resolution; and community workspaces and tools.

The boundary of communities is often defined sharply, as it is essential for it to keep and strengthen its identity. People like others who are similar in preferences, attitudes, and values, leading to common identity and interpersonal bonds (Ren et al., 2007). The world outside of the community is therefore often only considered implicitly. As a result, many communities operate within boundaries that are de facto more or less solid and exclusionary. Such hard to cross divisions can also be reinforced by the many types of theoretical, technical, conceptual and use based e-collaboration boundaries that constrain the growth of communities of practice in organizations (Kock and Nosek, 2005).

Still, no community exists in isolation. Instead, each community is embedded in a much larger context. What is this context? What exactly is beyond the boundaries of communities? In particular, what socio-technical role is played by the technologies that communities use for enabling interactions beyond community boundaries? How to cross the boundaries using those tools?

Key to enabling communities are socio-technical systems: systems that use technology to connect people socially (Whitworth, 2009). Just as community research in general often focuses on the inner processes of communities, socio-technical systems design for communities has also traditionally focused on intra-community issues, such as sociability and usability of particular community systems (Preece, 2000). Even where multiple local groups and sub-communities interact in traditional "community networks" - computer-based networks created by and for a local community - they are still fully in control of their own socio-technical systems (Carroll, 2012).

Issues of control have to do with governance: the way in which a state, organization, community and so on is governed. A community informatics perspective on Internet governance sees

"the Internet as a social environment, a community space for people to interact with the expectation that principles of equity, fairness and justice will prevail. Internet governance must ensure that this online social space functions effectively for the well-being of all." (CI Community, 2013).

In an ever more networked collaborative world increasingly working in "The Cloud", the governance of socio-technical systems supporting communities is much more complex than that of local community networks. Collaboration increasingly takes place in - often global - networks of communities, raising complex issues about conflicting social norms, policies, and governance. It is therefore ever more unclear who is in control of the community tools and in what way, complicating the design and configuration of these tools.

The days are gone when a community installed its own server in an open Internet with transparent, stable protocols (see e.g. Caroll (2012) for many classic examples). Communities make ever more use of third-party social media and networking tools such as Facebook and LinkedIn. This means that they have only limited control over the configuration and implementation of these tools. Full control means that a community can itself determine what functionalities their tools offer; how these tools are configured; how the tools are linked to other tools and who has access to their functionalities.

In this exploratory paper, we outline some issues of inter-community socio-technical systems governance. Our purpose here is not to solve these issues, but rather to raise awareness about the complexity of socio-technical governance issues encountered in practice. We aim to expand on the rather abstract definition of community-based Internet governance cited above, exploring how it plays out in practice in actual collaborating communities. We introduce a simple conceptual model to frame these issues and illustrate them with a concrete case: the drafting and signing of the Community Informatics Community's "Internet for the Common Good"-declaration (CI Community, 2013). We show some of the shortcomings of and socio-technical fixes for Internet collaboration support in this particular case. We end this paper with a discussion on some directions for strengthening the collaboration commons.

The Socio-Technical Systems Governance Gap between Communities

When zooming in on the role that technologies play in enabling communities, an inward, single community view is often taken implicitly, from studies that examine how blogs can support a specific educational classroom community of teachers and students (Byington, 2011), to immersive virtual worlds, like Second Life, where the community literally only exists within that world (Twining 2007). These are valid and necessary research topics, but leave questions about the "socio-technical systems gaps" between collaborating communities wide-open.

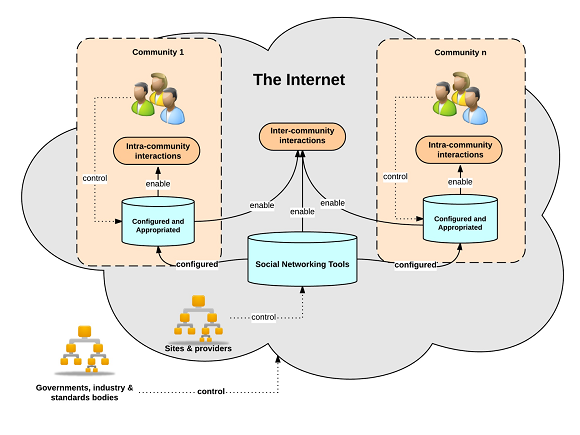

In the literature, work that explicitly acknowledges the embedding of the community within the larger outside world has generally focused on the immediate organizational context of a community. One example is how to create an organizational community and align it with organizational strategies, objectives and practices existing outside that community, such as companies promoting knowledge management through communities of practice (e.g. Wenger et al, 2002). Another example of embedding communities in a larger context is to examine how conversational technologies, such as wikis, can contribute to the emergence of a culture of collaboration and innovation and community building within the organization (Standing and Kiniti 2011). However, in the governance of the socio-technical systems of collaborating communities outside of the organization, that context is even more complex. To get a better sense of the issues involved, we introduce a conceptual model of inter-community socio-technical systems governance: who is in control of what (Fig.1)?

The model indicates the following:

First, communities often have a whole range of physical (e.g. town hall events and face-to-face meetings) and digital tools (from websites to a wide array of social media) to enable their interactions. In the early days of the Internet, these digital tools were often self-installed open source servers, fully controlled by their communities in that they provided exactly the functionalities needed for the community to effectively use and appropriate the tools.

Second, with the arrival of The Cloud, communities increasingly depend on community tools that are part of external social networking tools controlled by private parties. For example, many communities use Facebook or LinkedIn groups as their main online community space. The community can now only partly control the use and configuration of these groups. For example, Facebook decides which functionalities are offered (and withdrawn), what configuration options are offered and allowed, who has access (you need a Facebook, not a community account, to access most functionalities), and who gets to see what content. The traditional open architecture and implementation is under threat by the increasing balkanization through such walled-off cloud services. This restricted access could even jeopardize the "generativity" of the Internet, its trademark capacity to produce unanticipated change through unfiltered contributions from broad and varied audiences (Zittrain 2009, p.70).

Third, things get even more complicated when inter-community interactions need to be supported. When two communities want to collaborate, on, say, a joint project, there is often literally no space for that. It has to either take place in one of the current community spaces, a public third-party site is used, or a new private workspace needs to be created to which members from both communities need to subscribe, muddying governance and fragmenting collaboration before it has even started. Since "Code is Law" (Lessig, 1999), making context-free choices about seemingly abstract technical issues can have great impact on the legitimacy of and trust in the socio-technical systems of single communities (Whitworth and De Moor 2003). When such tools serve interactions between multiple communities with different social norms and modes of governance, complexity abounds even more.

Finally, more issues of control emerge at the level of the Internet as a whole. This is the level typically controlled by governments, industry and international standards bodies. The Internet was formed through a deep sense of community, leading to open protocols and an ethic of sharing: an excellent account of how this culture came about was given by Turner (2006). Still, this model is under threat, as for example the increasing privatization pressures (Németh, 2012) and the hotly debated issue of net neutrality - the idea that Internet service providers should treat all websites and services the sameii - show. Large political and commercial interests are at stake, but awareness is growing and a counter-movement is building (e.g. CI community, 2013). In this paper, we will not further look into these Internet-level issues, but this "outer context" should always be taken into account when developing local solutions.

Communities Taking (Back) Control of Their Tools in Common(s)

Collaborating communities can only influence their technical systems to a certain extent, given that so many layers of Internet technology control are involved. They therefore need to construct their own tailored socio-technical systems to ensure that social requirements are satisfied, as the legitimacy of the behaviors these systems afford and constrain (Whitworth and De Moor, 2003). These solutions will differ, depending on the specific requirements and social contexts of inter-communal collaboration. They will not be optimal solutions, given their complexity and limited degrees of freedom, but should at least be sufficient for meeting the social requirements.

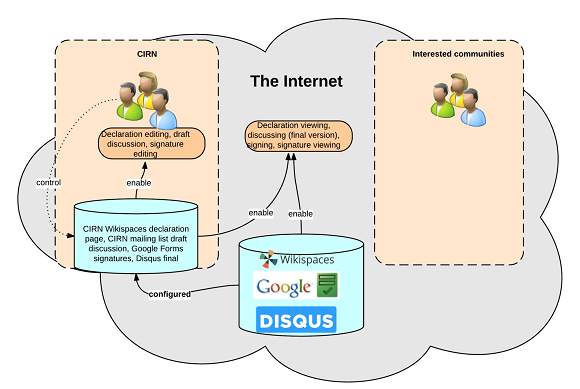

To give a flavor of the issues involved, we briefly examine the case of how the An Internet for the Common Good-declaration came about (Fig.2). This declaration purports to support communities worldwide to get more of a say in Internet governance (CI Community, 2013).

The idea for the declaration emerged in the Community Informatics Research Network (CIRN). This is a worldwide community of over a thousand researchers and practitioners. Their main physical interaction tools are an annual conference, several related conferences and workshops, and many meetings between various constellations of members. Their digital infrastructure consists of a very active mailing listiii for communication between members, and a wiki as its portal,iv The mailing list is hosted by a community network and the wiki is hosted by Wikispaces.v Both the list archives and wiki can be viewed by anybody on the Internet, while wiki edits can only be made by community members after having been admitted as a wiki member by an administrator.

The declaration was prepared by the CIRN Community. To this purpose, an initial draft was posted on a publicly viewable wiki pagevi . Community members were invited through the mailing list to participate in further drafting, for which they needed an account on the wiki. The community as a whole was kept informed about progress on the declaration through the mailing list. Legitimacy for the community of the final declaration was ensured through a process of "lazy consensus",vii by which consensus is assumed if nobody objects within a reasonable amount of time, in this case taking into account global time differences.

Once accepted, the process of getting it signed and published got underway. Both individuals and organizations could sign the declaration through a Google Form which collected signatures in two Google Spreadsheets. Both spreadsheets were embedded on the wiki page of the declaration, showing both individual and organizational signatories to the world. This page was then widely advertised by the members of the CIRN and many other communities, using e-mail and various social media tools.

Several inter-community socio-technical governance issues and solutions come to mind, for example:

- The declaration was developed within the CIRN community, but was to be signed by representatives and members of many other communities. The (technical) fact that one needed to be a CIRN member to be able to edit the wiki could have hampered involving members from other communities in the co-authoring. Still, in this case, the most pressing (social) reason for only involving the CIRN community in the drafting was lack of time. This is where the need for a common digital space (e.g. by virtually merging the memberships of all constituting communities) was clearly shown.

- The spreadsheets were maintained by administrators from the CIRN community. Sometimes, they had to remove signatures at the request of signatories or in case of spam. Although the administrators are trusted by the CIRN community, they may have been unknown to members from other communities intending to or having signed. Even though the spreadsheets have a revision history, this is only visible to the administrators. Since there was no way to show these revisions in the signatures to (potential) signatories, this may have reduced inter-community trust.

- To involve members from other communities in the evaluation and further development of the declaration, the final text also needed discussing. Wikispaces has a discussion page associated with each wiki page, which could be used for this purpose. With a restricted membership wiki like the CIRN wiki, such discussions are visible to anybody, but one needs an account on the wiki in order to post a comment or reply. Yet, in order to get such an account, one has to be a member of the CIRN community. An alternative solution opted for in the end was to embed Disqus viii widgets on the CIRN wiki. These widgets are hosted on an external website and allow discussion posts by Disqus members, but also by guests, thus circumventing the limitations of the intra-community discussion functionality of Wikispaces.

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this short exploratory article was not to provide an exhaustive analysis of, let alone a worked out approach for, inter-community socio-technical governance issues. Rather, our objective was to draw attention to the fact that collaborating communities co-exist in a very complex context of relations and interactions with other communities, supported by a multi-layered technical infrastructure, and that paying more in-depth attention to socio-technical design problems and solutions matters. Such solutions are not a technological quick fix, but consist of complex systems of online and physical conversations, collaborative intra- and inter-community workflows, roles, trusted persons, Internet infrastructure, third party tools, and tool configurations.

One research direction to explore could be collaboration patterns, which represent reusable socio-technical lessons learnt, some examples of which were suggested in the case. One key type of collaboration pattern is communication patterns, which describe acceptable and desired communicative interactions within a community, as well as the roles, content, and supporting tools involved (De Moor, 2006). Such patterns can be used to capture, compare, analyze, and compose the conceptual building blocks of more trusted socio-technical systems for collaborating communities (De Moor, 2009). Woven together in full pattern languages, they might even become critical enablers of civic intelligence, informing the implementation of, for instance, the Liberating Voices pattern language for communication revolution (Schuler, 2009).ix

Jordan et al (2003) talk about an "Augmented Social Network" where identity and trust is built into the architecture of the Internet by working out ways for persistent online identity, interoperability between communities, brokered relationships and public interest matching technologies. Such architectural elements could - in future research - further inform the definition of reusable collaboration patterns, grounding community-specific socio-technical configurations in more stable generic identity and trust-patterns. Other sources for inter-community collaboration patterns could, for instance, be drawn from community network studies, which focus on the interaction patterns within community networks and the role their community groups play in creating a more civil society through community activism (Kavanaugh et al., 2005; Carroll, 2012).

The commons is a public space, characterized by (relatively) open access, unmediated deliberation, and shared participation (Németh, 2012). There are many efforts to build and strengthen the commons, such as commons-oriented open peer production models with common ownership and governance models (Bauwens and Kostakis, 2014). Our focus in this paper was on the design of the commons as the socio-technical interaction spaces between communities. Communities and the commons are two sides of the same coin. Communities need a commons to inter-operate; the commons will not flourish without communities effectively contributing to and using them. Through eliciting socio-technical patterns for the commons which address not only fundamental architectural principles, but also the detailed socio-technical affordances and constraints of real communities in interaction, the commons could be further strengthened, in theory as well as in practice. These patterns could not only be used to inspire the design - involving civil society, governments, and corporations - of specific inter-community collaboration systems, but also strengthen the more generic building blocks of the commons: open source tools, platforms, protocols, and so on.

We have sketched only some of the multitude of issues that communities need to address when building their collaboration infrastructure. We hope that the awareness raised will inspire others to work on analyzing, designing and implementing more accessible, legitimate and usable socio-technical commons building blocks. Through such a collaboration commons, communities can focus more on joining and applying their forces, instead of re-inventing their technological wheels.

Endnotes

i This is an extended version of the

position paper presented at the Communities &

Technologies Vision Workshop, Siegen, Germany, January

22-24, 2014.

ii http://www.theopeninter.net/

iii http://vancouvercommunity.net/lists/arc/ciresearchers

iv http://cirn.wikispaces.com/

v http://wikispaces.com

vi

http://cirn.wikispaces.com/

An+Internet+for+the+Common+Good+-+Engagement%2C+Empowerment%2C+and+Justice+for+All

vii http://nowviskie.org/2012/lazy-consensus/

viii http://disqus.com/

ixhttp://www.publicsphereproject.org/patterns/