Users and Uses of Internet Access Points in Bangladesh: A Case Study of Community Information Centers (CICs)

- Lecturer, Department of Communication, University of Wisconsin, Whitewater, USA. Email: Delwarif@siu.edu

- Associate Professor, School of Journalism, College of Mass Communication and Media Arts, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois, United States.

The objectives of this study were to look at the patterns of uses and operations of Community Information Centers (CICs) in Bangladesh. The increased use of Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) such as Internet and mobile phones has rapidly changed the communication landscape of the world. ICTs are allowing people to communicate and interact in diversified ways. Scholars (Gurstein, 2011; Fountain, 2001; Jabbar, 2004; Karan, 2004; Layne & Lee, 2001) found ICT applications in political, business, health and agricultural related news and information. The demand for ICTs has been growing rapidly and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2009) stated, "Today, the innovations and technological advances in the ICT field are far outpacing the evolution in development thinking and practice" (p.1).

Even with the revolution of information communication, there is a large digital divide between developed and developing countries in terms of access and use, along with social and economic constraints. According to the declaration (known as "A Community Informatics Declaration") of the Community Informatics Research Network (CIRN Commons, 2013), "Effective use of the Internet will benefit everyone. Currently the benefits of the Internet are distributed unequally: some people gain power, wealth and influence from using the Internet while others struggle for basic access," (p. 1).

However, policy-related emphasis for access to new media in developing countries has changed the way people communicate with each other. Cyber kiosks, CICs (Gurstein, 2014) and cyber cafes have become access points for information and entertainment. Gurstein (2010) emphasized the role of CICs, and stated that these centers continue to be the primary means by which computing and the Internet is being made available at the community level.

In most countries E-Government strategies are increasing transparency and accountability with greater citizen interaction and empowerment of better-informed citizens. Technology is reaching even the poorest people who are accessing the Internet through some social sharing, which means that people are sharing the cost with others who have access to the service. This is a great revolution for people who live in remote areas in the developing countries and thus get access to information related to social, political and business issues (Rice, 2009).

It has been stated that information is power and those people who have much information are considered powerful in society (Zhao, 2008). Information-rich societies are more empowered to take reasonable decisions on socio-economic matters affecting their lives after evaluating available alternatives. Developing countries have understood these issues, and policy makers have started working toward increasing access to ICTs for development (Karan, 2004; Rice, 2009; Zhao, 2008). According to the UN department of Economic and Social Affairs (2009), "Almost all governments across the world have embarked on a long process of continuously integrating ICTs into their development policies and programs by formulating e-strategies and incorporating ICTs into poverty reduction strategies" (p.1).

According to Zhao (2008):

The massive processing power of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has fundamentally transformed the traditional ways of storing, processing and disseminating information, which in turn creates new possibilities in generating economic growth, increasing life span, promoting universal primary education and enabling informed participants" (p.17).

Bangladesh is one of the developing countries in South Asia where national policies are being framed with an emphasis on increasing infrastructure networks to reach the urban and rural areas. Apart from these, many community initiatives have started by building information centers, and several corporate organizations have come forward in this process of infrastructure development, training and access (Jabbar, 2004). In Bangladesh, the Grameen Bank started an initiative to provide Internet facilities to rural people through the CICs. The popularity of these centers is allowing people to access the Internet, collect information, and interact with people. Youth have been the biggest beneficiaries of this initiative and are extensively using the Internet kiosks for education, information and entertainment. This study, through a theoretical framework-using case study and survey approaches, investigates the uses and benefits of these CICs and the several ways in which the CICs are impacting the lives of the rural people in the country.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Communication in Development

The significance of using communication in the development process has been extensively discussed, positively resulting in the building of information societies and also contributing to coordinating development support initiatives for the country. The earliest scholars (Lerner, 1958; Rogers, 1976; Schramm, 1964; Rao, 1966) showed the advantages of using ICTs in changing societies. Melkote and Steeves (2001) highlighted the importance of communication in the development process. According to them, "The links are perhaps most evident in the case of the information transmission view of communication and the modernization perspective on development. For those who view communication as a process of message delivery, it is easy to view development as a process of modernization via the delivery and insertion of technologies, and/or inculcating certain values, attitudes, and behaviors in the population" (p.38). Schramm (1964) emphasized the role of mass media in national development in developing countries, particularly for agricultural and industrial development. Arguments of early scholars were based on the notion that people who did not have any access to media were not able to get information about changes in modern life. So, most people in third-world countries were not able to change their conditions, not because of lack of natural resources, but because of lack of access to information.

The expansion and development of mass media has supported development through communication and helped in the dissemination of innovations and information to people in communities. Mass media acted like "magic multipliers" for development. Everett Rogers' (2003) research systematically posited the role of media in the development process. With the notion of 'diffusion of innovation,' Rogers (2003) showed how communication is one of the important elements in the four step innovation process. According to him, "Diffusion is the process in which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system. It is a social type of communication, in that the messages are concerned with new ideas" (p.5). In the communication process, mass media act as channels of diffusion. Lerner (1958) described mass media as the "most rapid and efficient means of informing an audience of potential adopters the existence of an innovation - that is, to create awareness and knowledge," (p.18).

This theory has been widely applied in the development sector, particularly in agriculture, public health, and disaster management. In developing countries, policy makers and development practitioners use mass media to disseminate information to make people aware of important public health issues such as uses of sanitary latrines, washing hands after using restrooms, etc. By educating people through mass media and other channels, many health related problems have come under control in third world countries. (Melkote and Steeves (2001, Rice, 2009; Rogers, 2003)

New Communication Technologies and Development

With the inception of the Internet and new communication technologies, the debate over the role of media as learning institutions receives increased attention by scholars. The Internet and new communication technologies have changed the media landscape and audiences have become interactive. Hence, audiences sometimes become suppliers/producers of news (for example the "i-Reporters" of CNN,) and sometimes the audience becomes the producer of news. Xenos and Moy (2007) analyzed the 2004 American National Election Studies and found a significant correlation between the roles of the Internet and providing political news. The Internet is not only providing news about political affairs, but also many issues related to development and social change. Rogers (2003) also highlighted the contribution of the Internet and said it is possible to provide information to a large number people through a single e-mail. He stated, "For certain innovations, diffusion via the Internet greatly speeds up an innovation's rate of adoption" (p.216).

Melkote and Steeves (2001) confirmed the immense opportunities in the third-world countries to use the Internet for rural development (p.258). They specifically mention the role of the Internet in five areas of development: agriculture, community development, participatory communication, small business and international news flow. Karan (2004) in a study of seven Asian countries on the role of ICTs found that the Internet has been extensively changing the media landscape in Asian countries; people living in rural areas are getting information about diverse issues through various forms of new media. According to this author, the Internet is helping people to participate in local development, community activities, and social responsibilities. Referring to the rural cyber cafes used by farmers in Asian countries, she said, "Cyber windows with the 'Magic box' are helping these so far deprived and exploited farmers and rural poor to access and share information. It is now common to see farmers and vendors waiting at cyber windows every morning to get market information and weather conditions before setting off for work armed with the latest information" (p.10). Konieczny (2014) concluded that the pattern of empowerment via ICT is traceable throughout the history of human civilization and is continuing with the advancement of the recent technological revolution. Developing countries in Asia need to benefit from ICTs for their economic development and social change. In the online journal, Digital Review of Asia Pacific, Butt and Sarker (2010) stated that even though the countries in this region have been working to develop infrastructures, content, and policies to use the facilities of ICTs to accelerate the process of development, more steps need to be taken to receive benefit in certain sectors like gender and environmental sustainability.

Digital Divide

Despite the fact that communication scholars (e.g., Selwyn, 2006; Selwyn, 2004; Selwyn 2003) and policy makers have stressed the essence and significance of ICTs for a long time, it is also a widely accepted fact that people across the world do not have equal access to communication. According to Selwyn (2006), "…the underlying premise of the digital divides debate - i.e. that there is a perceived 'need' for all citizens to engage with ICTs in order to survive and thrive in the current information age," (p.289). Rogers (1976) also referred to the concept of Tichenor et. al's 'communication effects gap.' He said the concept was proposed, "to imply that one of the effects of mass communication is widening the gap in knowledge between two categories of receivers (those in the high and the low socio-economic status)," p.233. The Knowledge Gap theory also highlighted the issue and says that every new medium creates a gap between information-rich and information-poor people. Those people who have high social status would get more benefit from a new medium compared to those people who have low social status (Viswanath & Finnegan Jr., 1996).

However, the lack of access has resulted in a 'digital divide' between the Developed and Least Developed Countries (LDCs). Rice (2009) found wide gaps between people who have access to ICTs and those who do not have access. He emphasized the importance of ICTs in social transformation and expressed hope for the inclusion of people living in rural areas in the developing countries, particularly for farmers to get know about agricultural products, new techniques of farming, banking, and other citizen services. According to a United Nations' (2010) website of the, "Data collected by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) over six years revealed that, while still significant, the digital divide was shrinking slightly accompanied by falling Internet and telecommunications costs between 2008 to 2009 worldwide but the relatively high cost of Internet broadband services still deserved concern from policymakers."

Howard et. al (2010) found a digital divide within the countries, whether they are developed or developing. As an example, they discuss the case of Canada and the U.S. and mentioned various reasons for wide gaps in providing access to information communication technologies. Bogner, Tharp and McManus (2014) also found evidence of a digital divide among ICT users in the U.S. In this regard, the conceptual foundations of the digital divide provided by Selwyn (2004) is well-rounded compared to the conventional theoretical framework. In his definition, Selwyn went beyond the traditional dichotomous (have and have not) categories. He advocated reconsidering the concepts such as, access to and use of ICT and concluded his arguments by defining digital divide as, "a hierarchy of access to various forms of technology in various contexts, resulting in differing levels of engagement and consequences," (p.351).

Community Development and CICs

The notion of community development refers to the involvement of citizens and professionals to build a strong local community. Hence, the process of community development involves empowering a group of people through skills that are required to bring changes in the communities. According to the Website of PeerNetBC (2014), community development is a process that requires community members to come together for collective action to solve a common problem. Ferguson and Dickens (1999) defined community development as "asset building that improves the quality of life among residents of low-to-moderate-income communities, where communities are defined as neighborhoods or multi-neighborhood areas," (p.5).

In this regard, the relationship between CICs and community development is obvious. As many people get access to communication by using the Internet in CICs, they become more involved in the process of community development. In addition, CICs allow people to learn new information communication technologies, which have become imperative for personal and professional development in this age of the Internet.

New Communication Technology initiatives in Bangladesh: Grameen Bank, Grameen Phone and CICs

Bangladesh is one of the most populated and poorest countries in the world. According to the website of the Central Intelligence Agency (2010), currently 156 million people live in the country and more than half the people (52.1%) are illiterate. Most people do not even have access to traditional media. Despite the fact that governments have been trying to promote the ICT sectors since the 1990s, the growth of Internet users is not very high compared to the population of the country. Most of the current Internet users are the urban rich, and the poor in the urban areas and rural populations do not have adequate access to the Internet (Islam & Tsuji, 2011). As rural people do not have access to other media outlets, they lack access to information or any sort of communication.

Given the impact that ICTs can have on the development process in the country, the government is developing infrastructure and expanding networks in the country's rural areas. Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) are being encouraged to reach people in urban and rural areas. A series of efforts have resulted in the development of community-based Internet service facilities in the rural areas of Bangladesh. Even though many people may not be able to access these centers, trained persons serving as 'opinion leaders' operate the centers and provide information from the Internet to the people as well as disseminating information to persons as required.

Grameen Bank started in Bangladesh in 1976 by Dr. Muhammad Yunus under a project aimed at offering banking services to the poor living in rural areas and to support farmers and the underprivileged by giving them loans at very low interest rates. The bank and Dr. Yunus won the Noble Peace Prize in 2006 for their contribution in building peace by alleviating poverty. One of the additional activities of the bank has been to develop the Grameen phone to connect the poor farmers. As well, to help poor people overcome exploitation by the moneylenders, they also started the CICs.

CICs of Grameen Phone

Grameen Phone established the CICs to provide information to those people who lacked Internet access and soon these CICs were started across the country, with many people reaping the benefits from these centers. Islam and Hoq (2010) found that different CICs have been playing an important role in socio-economic development in Bangladesh.

Grameen Phone, one of the leading mobile phone providers in Bangladesh, started a new community initiative to provide facilities of Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) to the people in 2006. To facilitate the process, the phone company set up CICs throughout Bangladesh. According to the website of Grameen Phone (2014), more than 500 CICs have been established in 450 Upazillas (local districts) in Bangladesh. The objectives for establishing these CICs include "bridging the 'digital divide' by providing information access to rural people, alleviating poverty, educating the underserved and underprivileged on information-based services, building local entrepreneurships and improving capacity, creating employment opportunities for the unemployed youth." At these centers, people are able to use the Internet and mobile telephone facilities to connect with friends and relatives, get information from the government websites, apply for jobs, and get the latest information about market prices for agricultural and business products.

The target groups of these CICs are people who do not have any access to ICTs. Referring to the activities and uses of the CICs, Washington Post journalist Sullivan (2006) said, "The main purpose of these centers is to help people to download job applications and music, see school exam results, check news and crop prices, make inexpensive Internet phone calls or use Web cameras to see relatives. Students from villages with few books now have access to online dictionaries and encyclopedias," (A12).

As this review shows, many studies have described the CICs and the development of CICs across the country, but none have quantitatively analyzed the uses and impact of the CICs. This study focuses on the services of the CICs provided by the Grameen Phone and their impact on the users. The following research questions (RQs) and hypotheses were framed for the study:

Research Questions

- RQ1: How do people use the CICs and what are the types of information that they seek from the CICs?

- RQ 2: How are the trained personnel at the CICs disseminating information to reach the rural people?

- RQ3: What is the role and use of mobile technologies in supporting the CICs or being used independently for development?

- H1: Are more educated people more satisfied with CIC services.

- H2: More educated people will seek more news and information related to education and entertainment.

METHODOLOGY

Case study and survey methods were used to examine the patterns of use and impact of the CICs in Bangladesh. The case study method provides an opportunity to systematically use different sources of data to inquire about any issue or event. Wimmer and Dominick (2006) defined it as an empirical inquiry that uses multiple sources of evidence to investigate a contemporary phenomenon. A case study method was used to extensively evaluate the services of the CICs and patterns of uses of the centers, whereas the survey was aimed to get specific answers on the uses of the Internet. According to Tellis (1997), "Case study is an ideal methodology when a holistic, in-depth investigation is needed." Based on the principle of the case study method, the data collectors also conducted unstructured interviews with the operators and users of the centers.

Surveys provide an opportunity to get specific answers from respondents. Moreover, surveys are structured and help to get a variety of responses from many people. Two surveys (one for the users and the other for the operators of the CICs) with both closed and open-ended questions were used; the first was used to study the personnel operating the CICs in the country, and the second was used to study the impact of the CIC on the users. The questionnaires were translated into the local language to collect data from the local people not proficient in English. The questionnaires were brought back from Bangladesh, coded and analyzed at a university in the United States.

Pilot study: A pilot study was conducted to check the problems in the questionnaire on a sample of 5-10 members of the CIC and about 20 users of the CICs in Chittagong city to provide an opportunity to restructure the questionnaire after getting the feedback from the pilot.

Sample: There are more than 500 CICs around Bangladesh to provide different kinds of services (Website of Telenor Group, 2014). The centers provide Internet service to those people who do not have access to any media. For this study, data was collected from 100 users and 12 service providers of the CICs in Madaripur and Chittagong districts in Bangladesh. Two graduate students studying journalism in a public university in Bangladesh visited these centers to conduct the surveys and interviews.

Results

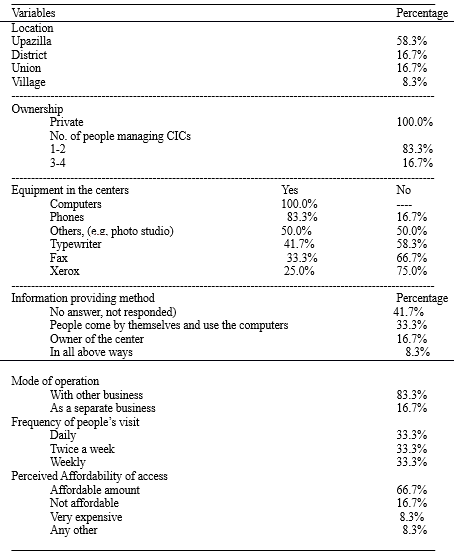

More than 500 CICs operate in Bangladesh. The first research question asks how people use CICs and what types of information people mostly seek from the CICs. The results (see Table 1) show that more than half (58%) of the centers are located in the Upazillas. Of the other locations, 16.7% are in districts and unions respectively. Districts, Upazillas, and Unions are units of local government administration. Where unions are in lowest level and Districts are in higher level of this local government system.

A detailed analysis of Table 1 shows that all the centers are privately owned. One or two persons who have been trained in the use of computers and are familiar with the software generally manage them in 83.3% of the centers. They are bilingual, (English and Bengali) to ease the process of translation when required. Equipment in the centers includes computers (100.0%), phones (83.3%), stationery and other supplies (50.0%), typewriters (41.7%), fax (33.3%), and photocopying machines (25.0%). About a third (33.3%) of the users are able to access the Internet and source out information for themselves while 16.7% of the users get information from the owners or people running the CICs. Nearly half the users (41.7%) did not answer the question. In terms of modes of operation, 83.3% of the centers were operated with other businesses, and 16.7% were being operated as independent businesses. According to the operators of these centers, there is a variation in the number of visitors on a daily basis. 33.3% of the people visit the centers daily, twice a week, and weekly respectively. In terms of affordability, nearly two thirds (66.7%) of the users found the cost of using the centers affordable, and less than one fifth of the users (16.7%) found the cost to be unaffordable.

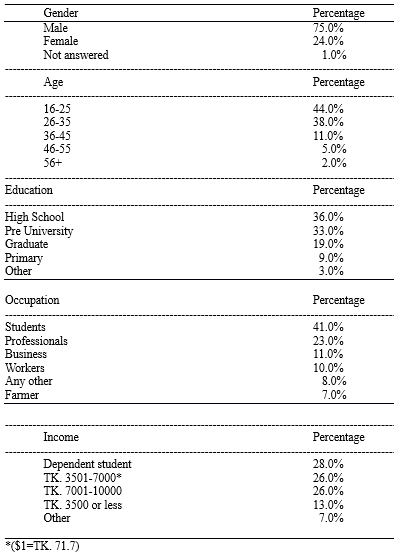

The survey provided insight into the background of the people and the types of information sought by the rural persons. The demographic profiles (Table 2) showed that three quarters (75%) of the users were male. In addition, most of the users (44%) are between 16 and 25 years.

More than four-fifths (82%) of the users were between 16 and 35 years, and only 7% are above 46 years. In terms of education, more than one-third of the users are educated up to high school and pre-university (36% and 33% respectively). Nearly one-fifth (19%) of the users have graduate degrees. Nearly half (41%) of the participants are students and more than one-fifth (23%) of the participants are professionals. The other professions of the participants are (in descending order): business 11%, industry workers 10%, and farmers 7%. In terms of income of the participants, nearly one-third (28%) are dependent students. More than half of the users have a monthly income of TK. 3501 to 7000 (around $100). More than one-fourth (26 %) of the users have monthly income of TK 7001 to TK 10000 (nearly $150).

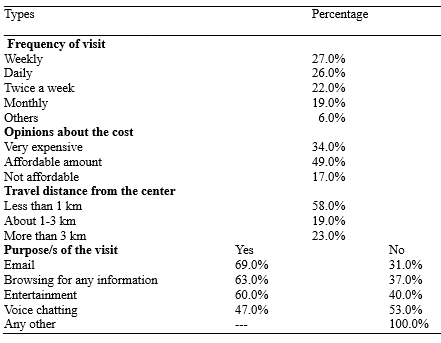

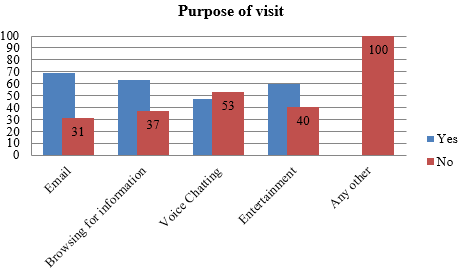

There was high to moderate use of the CICs. Table 3 shows that more than one-fourth of the users visit the centers weekly (27%) or daily (26%). About one-fifth (22%) visit the centers twice a week, and the least number of the users (6%) visited the centers less frequently, sometimes three to five times in a year. In terms of the cost of using the centers, nearly half (49%) of the users stated that the cost was affordable, more than one-third (34.0%) said it was expensive, and only 17% of the users indicated that the cost was not affordable. More than half (58%) travel less than one kilometer to come to the centers, and about one-fourth (23%) of the people travel more than two kilometers to reach the centers. Nearly one-fifth of the people (19.0%) travel about 1-3 km to come to the centers. In terms of purpose of visiting the centers (Figure 1), nearly two-thirds (69%) of the users mention that they come to the centers to send emails.

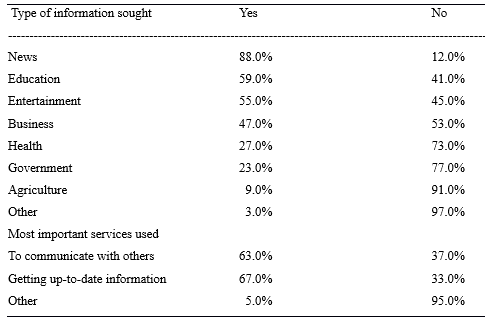

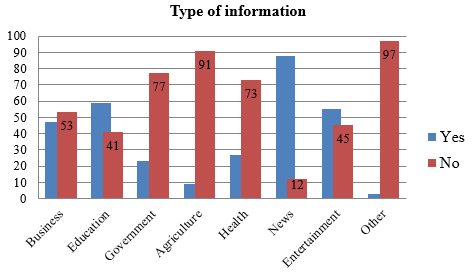

The other purposes of use are browsing for any needed information (63%), entertainment (60%), and voice chatting (47%). The types of information people sought from the CICs are news (Table 5, Figure 3) (88%), education (59%), entertainment (55%), business (47%), health (27 %), government (23%), agriculture (9 %), and others (3%). The users list job seeking and contact with husband and sons abroad as other types of information they sought in the centers.

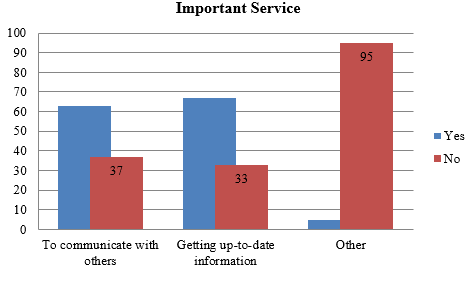

In terms of the most important services (Figure 2), 67% of the users stated that they used the centers to get up-to-date information about general issues, and 63% used the centers to communicate with others through emails. People also use the centers for other purposes include entertainment, watching movies, and listening music.

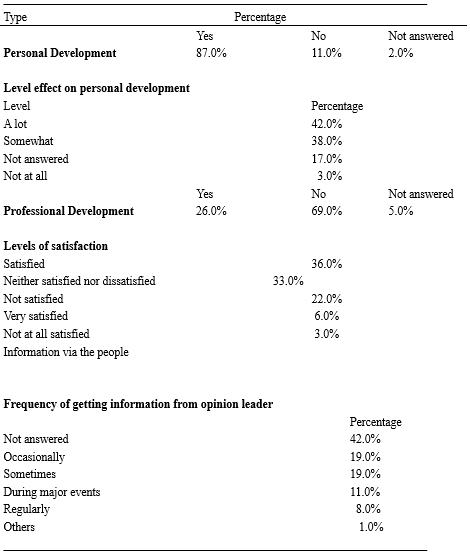

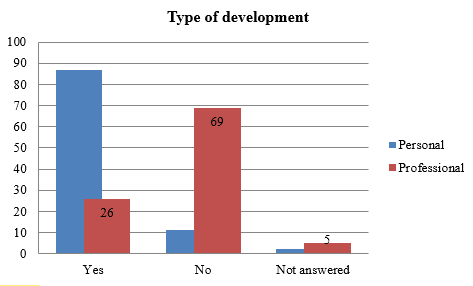

The data (Figure 4) shows that most of the respondents (87%) mentioned that the information was leading to their personal development as they were better informed. It was also helping them in their education, playing games, emailing, and browsing, and thereby increasing knowledge and learning. Nearly half (42 %) of the respondents stated that coming to CICs was helping them a lot in their overall development. Only 3% were not affected by the CICs at all.

Only 2% of the users were not at all satisfied, while two-thirds (67%) did not answer the question. In terms of satisfaction with the CICs, more than one- third of the users (36%) were satisfied. A third (33%) were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. About one-fifth (22%) were not satisfied. Only 6% of the people were very satisfied, and 3% were not at all satisfied.

The use of mobile phones is a new direction for sending and receiving messages. In terms of getting information from staff of the CIC, more than half (57%) of the users received the information while 42% did not. Among them one-fifth (19%) received the information from the opinion leaders both sometimes and regularly. More than one-tenth (11%) of the users got their information regularly from the opinion leaders (such as primary school teachers and religious teachers) during major events.

Hypothesis Testing: The first hypothesis predicted that the more people are educated, the more they would be satisfied by using the CICs. To test this hypothesis, a Chi-Square test was conducted. The results support the hypothesis. The Pearson Chi-Square value is 34.238, df=16 and p=.005.(Table 6) shows that a majority were very satisfied users (6) and had high school and pre-university degrees.

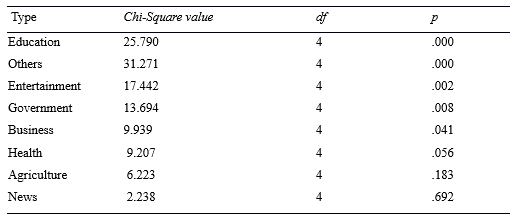

The second hypothesis predicted that more educated people would seek more news and information related to education and entertainment. To test this hypothesis, a Chi-Square test was conducted. The results in Table 5 show that the higher the education, the more they sought information about education (p=.000), others (p=.000) and entertainment (p=.002). However, this is not true for news (the Pearson Chi-Square value is .692). Therefore, this hypothesis is partially supported.

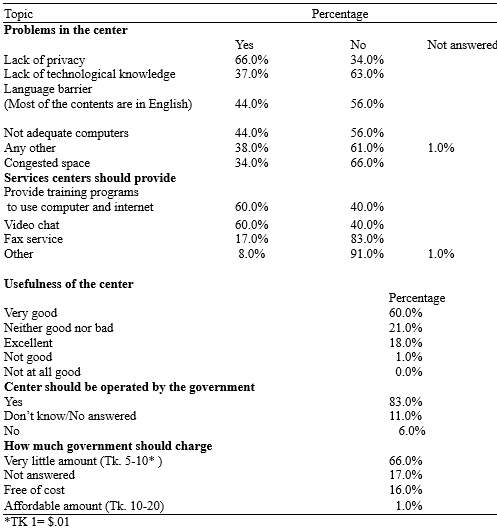

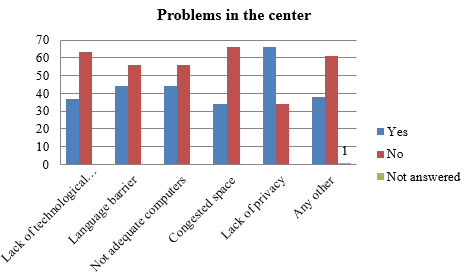

The second research question enquired about the problems faced by people in using the CICs and their suggestions for improvement of the centers. The results show (Figure 5) the three most frequent problems mentioned by the users were; lack of privacy (66%), language barrier (44 %), and inadequate number of computers in the centers (44%). Lack of technological knowledge and congested space are the least mentioned (37% and 34% respectively). More than one-third (38%) of the users mention some other problems in the centers, including slow Internet connections.

Users listed different services that the centers should provide, including planning a few training programs to use the computer and Internet (60%), video chat (60%) and fax service (17%). In terms of the usefulness of the centers, 60% found the centers to be very good. More than one fifth (21%) found the centers to be neither good nor bad, and 18% found the centers to be excellent. 83% firmly stated that the government should operate the centers, so that it would be better controlled and also ease the cost of usage. A majority of the users (66%) stated that government should charge a small amount (TK. 5-10) of money for using the services.

DISCUSSION

The objectives of this study were to look at the patterns of operations and uses of the CICs in Bangladesh. The results show some significant relationships on the operations, uses and gratifications by the people using the centers. Most of the centers are privately owned. The CICs were started with an aim to bridging the digital divides (Grameen Phone website, 2010), but it was found that the more privileged groups were using the centers (Research and Market, 2010). The results of this study showed that most of the centers (74%) are located in the districts and upazillas, which are basically suburbs of the district towns. Most of the users of these centers are from high socio-economic groups; 44% are young between the ages of 16-35, and 91% had undergraduate degrees. Only 7% of the users stated farming as their professions.

The data collectors for this survey (while interviewing the users and operators) found that most of these CICs are operated along with other businesses. The owners of the CICs run the centers as alternate businesses along with other businesses such as computer training centers, photo studios, photocopying centers etc. As a result, the CICs have become business centers instead of information service centers to cater to the rural poor. There is a need for greater PPP to provide better facilities and increase the use for government-related information and interaction.

As well, there are problems in the running and modes of revenue collected at the centers as observed by the researchers. The operators of the CIC in Hathhazari in Chittagong mention that Grameen Phone has supported them in providing some computers and software and established a partnership with the operators to establish the center. The users of the centers stated that only the trainees of the computer training centers are allowed to use the CIC as a cyber cafe. As a result, the users of this center have to pay high prices to use the Internet. The center does not provide the services that are outlined by Grameen Phone (such as ensuring the Internet facilities for the rural people). The situation was similar in other CICs that the data collectors observed. The operators of the centers blamed Grameen Phone for not following up after providing training and computers to check whether the CICs are functioning well and providing the required services to the people.

The results of the study also showed that there are several problems in these CICs in terms of infrastructure maintenance, training, operating, and the revenues charged for use. Hence, people do not frequent the centers, and the operators of these centers are not able to earn enough money. Even though more than half the users mentioned that the charges for using the centers are expensive, some CICs in remote areas also charge TK50 (more than half a dollar) for sending an e-mail. As people do not have any other option to get Internet access in those areas, they have to depend on the CICs for various purposes such as getting results of public examinations, sending emails, and application for jobs.

The results also show that more than one-fourth of the people are not satisfied with the services in the centers. In terms of the types of information they sought, most of the people mentioned news (88%), education (59%), and entertainment (55%). It can be inferred from this that people use the Internet as a mass medium to get information and entertainment. Our data collectors talked with people in Shibchar Upazilla in Madaripur district and found little publicity about the services of these centers. Most of these centers are also in semi-urban areas. Unless marginalized people in the society know about the facilities, they are not likely to access the services. Apart from a sign-board in front of the centers, there is no way that people know about these centers. Operators both in Chittagong and Madaripur stated that they do not get any salaries to run the centers. As a result, the operators are not motivated to provide services to the people and have to depend on other small businesses to survive.

People positively appreciated the initiatives of Grameen Phone in providing information though the CICs. However, they expect that Grameen Phone should be serious not only by committing to the CICs, but also effectively monitoring their progress.

CONCLUSION

The journey started by Grameen Phone in Bangladesh has generated more public and private interest in providing information for the people. Many telephone operators have converted to CICs to provide information services. The Bangladesh government has realized the need for CICs and has started more than four thousand information centers in the unions.

Many non-government organizations have also been working in the development sectors to understand the demands of the people in seeking online information. This exploratory study provides an opportunity to understand the patterns of the uses and operations, as well as the problems and challenges that CICs present to policy makers. Second, this study also provides an understanding of the need to improve the CICs to maximize the benefits to larger numbers of people seeking information for personal and professional development. There is a need for increasing the level of awareness, access, and frequency of use particularly among the rural people for whom the services are primarily intended. Earlier studies have provided results concerning farmers (Butt and Sarker, 2010; Selwyn, 2006; Zhao, 2004) using information for their daily benefit and not being exploited by middle men. At the same time there is a need for both money and training for the personnel running these centers. Governments will soon be switching to e-government and there will be a greater need for citizens to use the CICs.

Though the study provides important data, there are a few limitations of this study in terms of the sample and the location of study. Given the size of the country, and the limited resources available for the study, the sample was small as only two districts in Bangladesh were examined. A larger sample covering more districts in Bangladesh would add depth to the study. Secondly, the sample included only urban and semi-urban respondents, it would have been better also to have people from rural areas for comparison in the user's perceptions. However, these limitations do not negate the results of this study, and similar studies can be replicated in the future to monitor the changes and developments in the years ahead.