Assessment of Mobile Voice Agricultural Messages Given to Farmers of Cauvery Delta Zone of Tamil Nadu, India

1, 2, 3: IIT Madras' Rural Technology and Business Incubator, IITM Research Park, Taramani Chennai, India. Corresponding Author (email): ganesanmuthiah2009@gmail.com

*Formerly: Senior Project Officer, IIT Madras' Rural Technology and Business Incubator

INTRODUCTION

Enhanced farm productivity and farmers' livelihoods largely depend on how the relevant technology information and farm inputs are accessed by farmers. Singh (2011) reviewed various delivery mechanisms of agricultural extension services available to farmers in India. This study showed that an innovative approach towards farmers was practiced during the Green Revolution period for disseminating agricultural information to farmers in India. However, this approach had facilitated only resource rich and irrigated land holding farmers in utilizing the Government support while small and marginal farmers were not able to be part of this extension model.

In the earlier practice of extension, farmers were contacted on a one to one basis, which had been a very effective but an expensive and unsustainable practice. Another approach was the farmer field school which consisted of schools without walls where groups of farmers met periodically with facilitators during the crop season. An important learning from the farmer field schools was that of sustainability without outside funding sources. Singh further emphasized that a new approach using Information and Communication Technology for the dissemination of agricultural information that is relevant and reliable needs to be developed to achieve a real impact on farm productivity and livelihoods.

According to the National Sample Survey, only 40 per cent of the farmer households accessed information about agricultural techniques and inputs (NSS, 2005). Farmers access information from progressive farmers, input dealers, mass media, public extension workers, cooperatives, output buyers/processors, Government demonstrations, village fairs, study tours, Krishi Vigyan Kendras and private companies. But, the most important sources of information are progressive farmers, input dealers and mass media (Surabhi and Gaurav, 2009; Surabhi et al. 2010; Ashutosh et al. 2012). , ICT in different forms has been widely taken up in India by various local or national non-governmental organizations followed by private and public sector agencies (Saravanan, 2010), as a tool to disseminate agricultural information amongst farmers.

Mobile application plays a key role in fulfilling the agricultural information needs of the farmers as it has many advantages such as easy and convenient access, reach to areas where there is no other ICT infrastructure like internet, fixed lines etc., and is easily afforded by farmers (Ravinder and Vister, 2010). According to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, the number of wireless mobile phone subscribers has reached 867.80 million as on March 2013 and India is the second largest wireless market in the world (TRAI, June, 2013). Further, rural subscribers are continuously increasing every month, as compared to urban subscribers. The increasing trend in mobile phone use, particularly in remote rural areas, provides an opportunity to bridge the rural and urban digital divide.

Several mobile phone based agricultural extension projects have been deployed in India like, aAqua (Krithi et al. 2011), Avaaj Otalo, (Patel et al. 2010), mobile digital video (Rikin et al. 2009). Similarly, IFFCO Kisan Sanchar Limited (IKSL), BSNL, Reuters Market Light (RML), Nokia Life Tools, Fisher Friend Project, Rubber Board and Department of Agriculture, Haryana State provide services through SMS and Voice messages containing agriculture related information like market price, weather updates, news on agricultural policies and best agricultural practices (ICTFSECBP, 2009; Fafchamps & Minten, 2012; Saravanan, 2010). The Department of Agriculture, Government of Tamil Nadu, in collaboration with IITM's RTBI has been disseminating agricultural information to farming communities of five delta districts, through voice messages delivered on farmers' mobiles. For the farmer, the costs of the service are zero, as the messages, delivered as incoming voice calls, are free for farmers.

Dissemination process of mobile voice messages on Agricultural Information

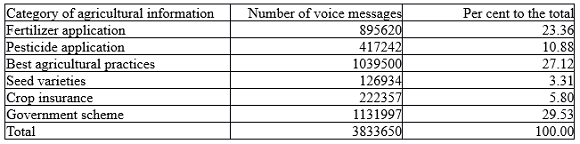

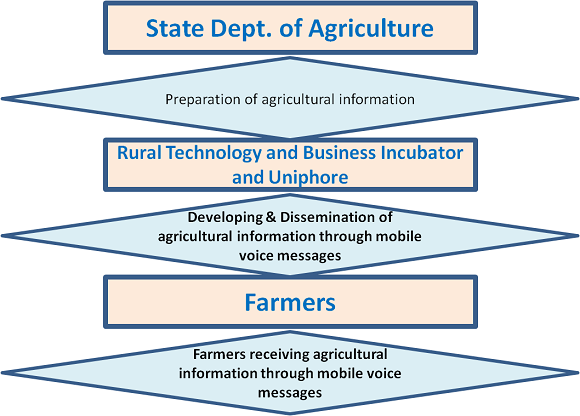

Figure 1 presents the dissemination process of mobile based voice messages containing agricultural information. The agricultural extension officials of the Department of Agriculture, in the state are responsible for preparing the content of agricultural information, while Uniphore Software Systems (the technology partner in this initiative and a company incubated by RTBI) is responsible for developing and dissemination of agricultural information to farmers' mobile number through voice messages. Information was sent on a monthly basis and the message duration lasted for a maximum of one minute. The messages were relayed during August, 2012 to July, 2013. From the call records, it was found that a total of 3,833,650 voice messages with an average of three to four messages per month per farmer were delivered to 123756 farmers- the messages contained agricultural information covering various aspects such as fertilizer application, pesticide application, best agricultural practices, seed varieties, insurance and government schemes. The analysis of the voice messages revealed that a large percentage of messages were on Government schemes (29.53%) followed by best agricultural practices (23.36%) and fertilizer application (23.36%). Table 1 presents the category of information disseminated through mobile voice messages to the farmers.

The present study mainly focuses on the assessment of

mobile voice message (containing agricultural advisory

information) service given to farmers in five delta

districts of Tamil Nadu.

The specific objectives are:

- To describe the socio economic characteristics of the farmers in the study area

- To find out the sources of agricultural information which farmers are accessing

- To find out the adoption level of agricultural information disseminated through mobile voice messages

- To examine the usefulness and trustworthiness of agricultural information disseminated through mobile voice messages

- To examine the level of satisfaction of farmers with the mobile voice messages in terms of audio quality, content and language of messages

- To determine the relationship between the socio economic characteristics of the farmers and adoption of agricultural information delivered through mobile voice messages

The remaining sections of the paper are organized as follows: Section 2 describes the methodology in which we outline the study area, sampling procedure & sample size, data collection & variable measurement as also data analysis and section 3 presents the results and discussion. Section 4 covers the conclusion and recommendations for further research.

METHODOLOGY

The Study Area

The study was carried out in five districts of Cauvery Delta zone namely Thanjavur, Thiruvarur, Nagapattinam, Cuddalore and Tiruchirapalli of Tamil Nadu, India (Figure 2). The study area lies in Cauvery delta agro climatic zone. It lies in the eastern part of Tamil Nadu between 10º-11º30' North latitude and between 78º15' - 79 º 45' longitudes. The total geographic land area of Cauvery delta zone is 14.47 lakh ha, which is equivalent to 11.13 per cent of the Tamil Nadu geographical area. This area experiences an average annual rainfall (mean) of 1078 mm and most of the rainfall is received during the North East monsoon season. Rice is the principal crop being grown here and the next important crops are pulses such as black gram and green gram, being grown as rice fallow crops. Vegetables like brinjal, chillies and greens are also being grown in a limited area in the well-drained fertile lands, depending upon the underground water source. In light clay loamy soils under garden land condition crops like groundnut, maize, gingelly and irrigated pulses are grown. Banana, sugarcane and ornamentals like jasmine, rose, chrysanthemum, crossandra and nerium are the annuals being grown. Coconut gardens, bamboo and wood lots are found scattered in the delta in different densities. Mangoes, Jackfruits, citrus of various kinds - guava, pomegranate and custard apple etc., are also being grown in specific pockets.

Sampling Procedures and Sampling Size

All the five districts of Cauvery delta region were selected for the study because all the registered farmers in these districts receive and participate in the mobile based voice messages initiative. The districts are Thanjavur, Nagapattinam, Tiruchirappalli, Thiruvarur and Cuddalore. This is followed by a convenient sampling of 40 farmers from each of the districts, forming a sample size of two hundred (200) farmers, for the study.

Data Collection and Variable Measurement

The primary data for the study was collected from the farmers through telephonic interview using a well-structured questionnaire, while the secondary data was obtained from journals, conference proceedings, internet etc. The farmers considered were those who had already registered their mobile number at http://www.tnagrisnet.tn.gov.in/website/index.php run by the State Department of Agriculture, Government of Tamil Nadu. The registered mobile numbers of the farmers were collected from the technology partner (Uniphore Software Systems, Chennai). The socio-economic characteristics of the respondents such as gender, age in completed years, education attainment in the form of primary school, middle school, high school, higher secondary school, graduate and post graduate, land holding size classified as marginal farmer (those who have <2.50 acres), small farmer( those who have 2.51 - 5 acres), medium farmer (those who have 5.01 - 12.50 acres) and large farmer (those who have 12.51 acres and above) as well as individual farming experience of the respondents were collected. The farmers were requested to inform about current sources from where they get agricultural information. This question was asked to compare the sources of information with the delivery of agricultural information via mobile phone through voice messages. Following this, the farmers were asked whether they adopted any of the information that was delivered through mobile voice messages. The farmers' perception of usefulness of voice messages was also captured (all of the messages were useful, most of the messages, few of the messages, and none of the messages were useful). Level of satisfaction over mobile based voice messages with regard to audio quality, simplicity of language and content of the voice messages was measured (Very satisfied, satisfied and not satisfied) and finally they were asked to answer whether the information that they received through their mobile phone were same or better than that of the current sources of information which they were accessing.

Data Analysis

Data collected for the study were analyzed with the use of simple descriptive analysis (frequency and percentages) and inferential statistic (Chi-square) using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Socio-economic characteristics of the farmers

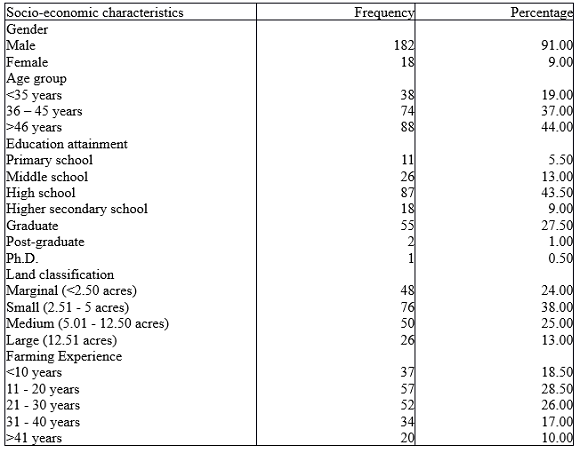

Analysis of the farmers' socio-economic characteristics was carried out and the summary of the result is presented in Table 2. Majority (91%) of the farmers were male while only few (9%) of the farmers were female. The higher proportion of male farmers could be due to the fact that most male farmers were primarily responsible for doing farming while females were assisting the males in most of the farming activities apart from doing other work such as manual transplanting, weeding and attending to value addition activities for their agricultural commodities. This might be because of the gender division of labour based on their cultural background as well as prevailing norms and values of the people living in the study area. This finding is in agreement with the report of Xiaolan and Shaheen (2012) who stated that the farming occupation was usually dominated by males though they were assisted by their female counterparts.

The data on age of the farmers shows that 44.00 per cent of the farmers were 46 years and above, 37.00 per cent of them fell within the age group of 36 - 45 years and finally 19.00 per cent of the farmers were below 35 years. This finding implies that most of the respondents were within the active age group of 45 years and below. Age factor was found to be significant in agricultural information accessibility and utilization (Meera et al. 2004).

The analysis of education of the farmers shows that most (43.50%) of the farmers had studied high school and 27.50 per cent of them had gone up to graduation and 13.00 per cent, 9.00 per cent and 5.50 per cent of the farmers had middle school education, higher secondary school education and primary school education, respectively. Two of them had studied up to post graduation and one had obtained a doctorate degree. Education is one of the important social factors that improve the attitude towards accessing agricultural information and their adaptation. The effect of education on adoption has been argued by several researchers. For instance, in separate studies, it was reported that education of the respondents was found to have significant relationship with their ability and interest to access agricultural information and its adoption (Ango et al. 2013; Rehman, 2013; Ani et al. 2004; Okwu and Umoru, 2009).

The landholding size distribution shows that 62.00 per cent of the farmers belonged to the marginal and small categories while the remaining 38.00 per cent were medium and large farmers. Those farmers with land holdings less than five acres constituted the highest proportion of the farmers. This indicated that the farmers in India are generally small and marginal farmers (Surabhi and Gaurav, 2009; Surabhi et al. 2009).

The years of individual farming experience show that 54.00 per cent of the farmers had been involving in farming activities for 11 to 30 years, while 27.00 per cent had farm experience of more than 31 years . This clearly suggests that farmers have got enough experience in cultivating and managing their agricultural crops.

Sources of Agricultural Information

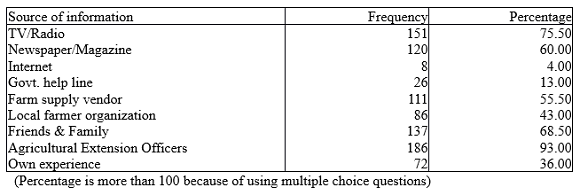

Table 3 has been furnished with data on agricultural information sources used by the farmers and the data reveals that majority (93%) of the farmers relied mostly on agricultural extension officers for obtaining agricultural information followed by television/radio (75.50%), friends & family (68.50%), newspaper/magazine (60%), farm supply vendors (55.50%), local farmer organizations (43.00%) and on their own experience (36%). With respect to getting information from agricultural extension officers, the result of the present study is contradictory to Singh et al. (2009) who found that extension officers were not regarded as a major source for getting information frequently. Several authors had reported that the most common source of information used by the farmers were progressive farmers followed by input dealers (Nitin, 2012; Ashutosh et al. 2012; Surabhi et al. 2009; Glendenning et al. 2010). Progressive farmers still act as an important source of information in India.

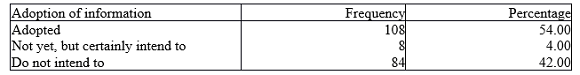

Adoption of agricultural information delivered to farmers' mobile phone

The main purpose of delivering information through mobile phone was to make farmers aware of the usefulness of modern crop management practices in enhancing a crop's productivity and subsequently to convince the farmers to adopt the technologies communicated. As indicated in Table 4, majority (54.00%) of the farmers did adopt the information disseminated through their mobile phone while 4.00 per cent of the farmers had not yet adopted the information, but they were certainly intending to adopt the information obtained through mobile voice messages in future, once they had sufficient confidence in the messages received. However, 42.00 per cent of the farmers mentioned that they were not interested in using the information in the near future as the information was irrelevant to them. On the other hand, the reasons for successful adoption of the information by some of the farmers might be due to the fact that these farmers got the relevant agricultural information at the right time. Getting reliable, relevant information in time was important for farmers for farm decision making as reported by Glendenning et al. (2010).

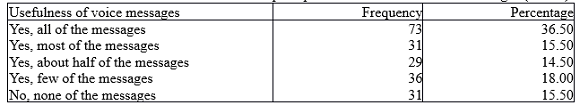

Usefulness of mobile voice messages

The mobile voice messages delivered to registered farmers contained agricultural information covering different aspects of fertilizer application, pesticide application, pest management, disease management, best agricultural practices, seed varieties, seed treatment, weeding and government schemes. The information was sent on a monthly basis and the message lasted for a maximum period of one minute. The messages had been relayed for about ten months with 10 - 15 messages being delivered on an average to each farmer. In order to understand the usefulness of voice messages, the farmers were asked how many messages they found useful in their daily farming practices. The findings are given in Table 5 and the results showed that 52.00 per cent of the farmers had expressed that either all or most of the agricultural information was useful, while 14.50 per cent of them expressed that information contained in half the number of messages was useful and 18.00 per cent of the farmers said that only few messages were useful. Only 15.50 per cent of the farmers indicated that none of the voice messages were useful to them. This might have been due to the information not being relayed to the farmers at the right stage of the crop or the information not being relevant to the crops they were growing.

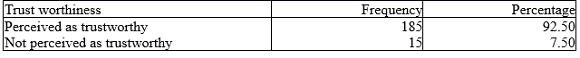

Trustworthiness of mobile voice messages

With regard to trustworthiness of the voice messages, the data from Table 6 reveals that 92.50 per cent of the farmers felt the information received could be trusted, while only 7.50 per cent of them felt otherwise. Patel et al. (2010) who conducted a field study of Interactive Voice Forum among the small farmers in rural India reported that farmers preferred to obtain information from known and trusted experts rather than from other farmers. This confirmed that the information source is certainly important for farmers to take farm decisions. Similarly, Surabhi and Gaurav (2009) stated that although mobile phone can help in disseminating agricultural information to improve the farm productivity and rural incomes, trustworthiness of information is one of the important aspects that need to be considered while delivering to farmers to meet their needs and expectations.

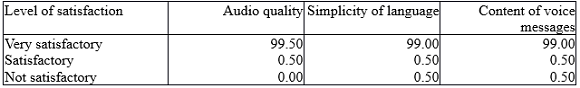

Farmers' satisfaction with mobile voice messages

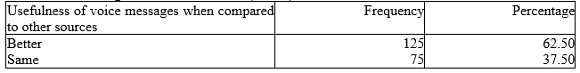

With reference to satisfaction level of farmers, the data from Table 7 indicated that almost all the farmers (100%) were very satisfied with the audio quality, simplicity of language and content of the voice messages. It implied that the agricultural information that was disseminated through mobile voice messages could be easily comprehended by farmers. Agwu et al. (2008) had carried out a study on adoption of improved agricultural technologies disseminated through radio farmer programme in Nigeria and stated that the level of satisfaction of individual farmer will largely inhibit their utilization of this source of information. With respect to comparison of mobile voice messages with other sources of information, the data from Table 8 indicated that majority (62.50%) of the farmers did express that the mobile voice messages were better as compared to other sources of information that they were accessing.

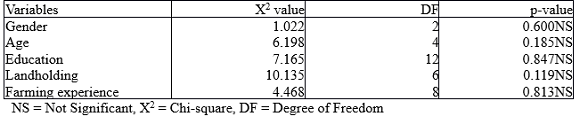

Relationship between socio economic characteristic of the farmers and their adoption of agricultural information disseminated through mobile voice messages (Table 9)

Farmer's decision on whether or not to adopt agricultural information relayed to them is an important variable that could determine the usefulness of the mobile voice messages. The socio economic characteristics like gender, age, education, land holding and farming experience may influence this decision either positively or negatively. The farmers were divided into three categories (farmers who have adopted the agricultural information, farmers who have not yet adopted but certainly intend to and farmers who do not intend to) for doing our analysis. The Chi square analysis was carried out on this data and the results show that all the socio economic characteristics of the farmers had no significant relationship with the adoption of information. There was no significant relationship between gender of the farmers and adoption of agricultural information disseminated through mobile voice messages. Similarly, age of the farmers had a non-significant relationship with adoption of agricultural information. This indicates that irrespective of age group (older or younger) and gender (male or female) farmers accept the agricultural information. Also education of the farmers had a non-significant relationship with the adoption of information. This could be, because, all the farmers were educated to some extent. Landholding size of the farmers had a non-significant relationship with the adoption of information. This implied that regardless of the land holding size the decision to adopt the agricultural information was uniform. Farming experience of the farmers also had a non-significant influence on adoption of the agricultural information.

The non-significant relationships in the present study indicated that adoption of agricultural information was unlikely to be influenced by any of the socio economic characteristics of the farmers studied. The findings are in line with Ani et al. (2004) who reported that age and farming experience of rural women farmers in Nigeria were not found to have any significant relationship with adoption of farm technologies. However, education was found to have significant relationship with adoption of information. Mamudu et al. (2012) reported that farm size, age and education of the farmers significantly influenced the adoption of modern agricultural production technologies in Ghana. Similarly, Agwu et al. (2008) indicated that age and farming experience had significant influence on adoption of improved agricultural technologies disseminated through radio in Nigeria.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the findings of the study, it could be concluded that mobile voice messages are an effective communication channel for disseminating agricultural production technology information to the farmers. The findings revealed that the majority of the farmers who listened to the agricultural information delivered through mobile voice messages were male and were within the active productive ages of 36 to 45 years. All the farmers were found to have received some form of education. It was also found that the majority of the farmers had adopted agricultural information received through mobile voice messages. It was observed that almost all the farmers were very satisfied with the mobile voice messages as they had effective audio quality and comprehendible content of agricultural information. Further, the language used to relay the information in the voice message was very simple and easy to understand by the farmers. Majority of the farmers were of the opinion that the agricultural information received on their mobiles was better than other sources of information they were accessing otherwise. Based on the Chi-square analysis, it was observed that the socio-economic characteristics of the farmers had no significant influence on the adoption of agricultural information disseminated through mobile voice messages. It indicates that irrespective of the socio-economic characteristics of the farmers, they were willing to accept agricultural information disseminated through mobile voice messages.

On the basis of the findings in this study, it is recommended that there should be a further research on the impact of mobile based voice messages on agriculture being practiced across the delta region, particularly for small farmers. The information can be collected through focus group discussions and individual interviews with farmers at the village level. The objective of this study should be to seek answers to: Are the mobile based voice messages providing a more effective way of fulfilling farmers' information needs for timely, relevant and reliable information? Are farmers benefitting from yield improvements as a result of adopting recommended practices such as new varieties, best cultivation practices, pesticide applications, fertilizer applications, etc., received through these mobile voice messages? The answers to these questions will have important implications for the department of agriculture in state and central governments, agricultural information service providers and policy makers.