Open government data (OGD) emerges as one of the latest in a series of initiatives that have drawn on a developing logic regarding the socially progressive potential of 'open' models of information production and distribution. Open initiatives, through breaking down knowledge to the raw data and code, and abandoning models of false scarcity that restrict access, interpretation, and re-use, suggest the possibility of a significant reconfiguration of modes of understanding and production that have previously been shaped by dominant interests. However, open initiatives such as OGD emerge into a historical process, not a neutral terrain. Within the UK the convergence of a range of political and civil society networks engaged in the shaping of OGD marks a fruitful site of analysis for beginning to explore the interaction of hegemonic capitalist institutions with modes of production and citizenship that potentially contest key parts of its logic.

Whilst some advocates of OGD define it as apolitical (or, highlighting the reductionism present in such claims, non-partisan), this article will evidence that a deep seated political struggle is in progress. The civil society OGD initiative can be understood as part of the wider emergence of a new 'bloc' of historical actors frustrated by practices, deepened within the neoliberal era, that restrict and create asymmetries in the flow of information at the same time as technologies have developed that ease its sharing. It is therefore important to understand the relationship between these OGD advocates and the historical context in which they emerge, the scope for dominant interests to shape the initiative and the necessary progressive interventions that might need to be made in order to counter this threat.

Whilst the dominant narrative of OGD is guardedly optimistic with regard to its progressive impact on society, some critical studies of OGD have begun to emerge that are primarily focussed on the "effective use" of OGD (Gurstein, 2011), its potential role in "empowering the empowered" (Benjamin et al, 2007; Wright et al, 2010), and contextualising OGD in relation to broader modes of governance (Longo, 2011). This article further problematises the dominant optimistic narrative, arguing that the shaping of OGD is open to significant contestation. The aim of the article is to critically contextualise OGD within contemporary capitalist processes, focusing particularly on the situation in the UK where the OGD initiative intersects with the UK government's programme of forced 'austerity' and marketisation of public services, in order to better inform the engagement of those acting for progressive ends.

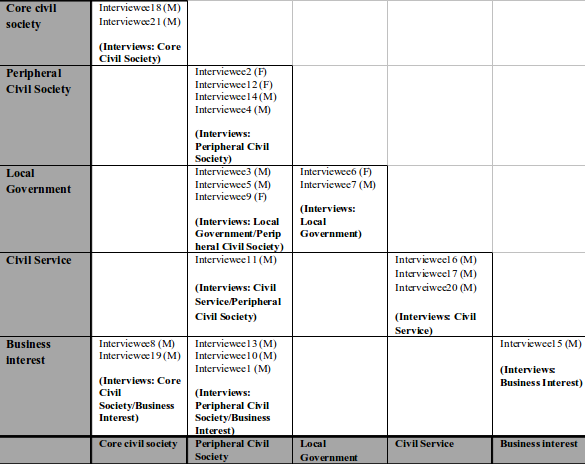

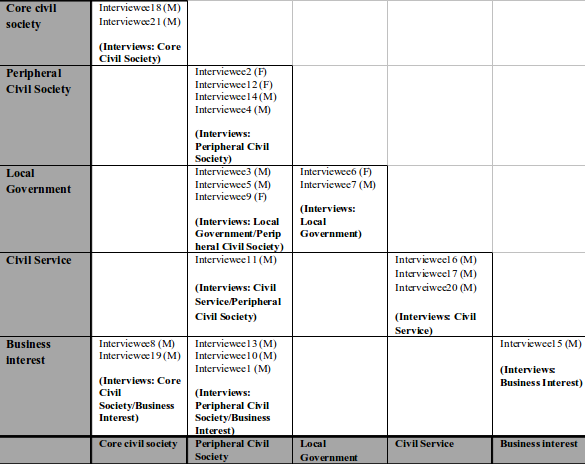

The arguments put forward are developed through interviews and attendance at a variety of local, national and international OGD events, complemented by analysis of academic and policy literature. Interviews were conducted during the period February to July 2011. Thirty-three potential interviewees were contacted between January and May 2011 through a process of purposive sampling, informed by event observation and desk research, in order to gain insight from a cross section of people and groups engaged in shaping the initiative. Two interviewees were also self selecting in response to a message about the research to the 'Open-government' Open Knowledge Foundation mailing list. The framework for selecting interviewees covered peripheral and core participants active within civil society OGD initiatives (where core participants were those that had at some point undertaken an official role advising the UK government on Open Data/Public Sector Information), as well as key players in local authorities, the civil service, and the private sector. Many of the interviewees were active in more than one of these areas, for example civil society and business, and these multiple areas of activity are represented in table 1. Interviewees were further categorised by gender. Unsuccessful attempts were also made to speak to politicians engaged in shaping OGD. In total, twenty-one interviews were completed.

The interviewing process began with those with more peripheral civil society engagement before moving closer towards the core, which primarily included government advisors, civil servant, PSI industry representatives. Interviews with those with more peripheral involvement were largely semi-structured and aimed at gaining understanding of participants' activity, ideas, and intentions regarding their engagement with OGD, and their interpretation of the OGD domain. Interviews with those closer to the core were generally unstructured and shaped around the time availability, background and experiences of interviewees. Whilst still exploring interviewees' ideas, intentions, activity and interpretation of OGD, these later interviewees were also used as 'expert informants', particularly in relation to policy issues and internal government politics. Due to the sensitive political nature of some of the discussions all interviews were carried out on the condition of interviewees' anonymity in the research report. This was designed to promote more open discussion with interviewees. Interview data referred to in the body of the article is therefore cited with reference to the category of interviewee (see Table 1 for category codes), rather than individual names or identifiers.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. In the next section, I introduce civil society advocates of OGD and their demands. I also discuss their definitions of OGD which situates their advocacy and role within the socio-economic domain. This is followed by a contextualising account of the political economy of valuable public datasets which has evolved in the UK over the last 40 years. The article then goes on to outline key policy developments around OGD and the broader field of Public Sector Information (PSI) re-use that have emerged recently, focusing on significant attempts by state actors, drawing on a neoliberal ideological current, to appropriate the initiative on behalf of dominant capitalist interests under the guise of a 'Transparency Agenda'. Next, significant sites of potential appropriation by profit seeking interests are highlighted and briefly discussed in relation to the impact that this could have on socially progressive ends. Finally, the vulnerabilities of civil society OGD advocates in their capacity to respond progressively to this situation are examined, prior to the article concluding by offering a number of recommendations for intervention in the shaping of OGD. The article, therefore, aims to outline the deep seated material and ideational structural processes that OGD is being developed within, prior to considering the potential for people to critically intervene and shape OGD for progressive ends.

This is in line with the Open Definition (OKFN [1], n.d.) developed by the Open Knowledge Foundation (OKFN), which takes substantial inspiration from the Open Source Definition (OSI, n.d.). The definition, therefore, stipulates that in order to be defined as 'open', licences are not allowed to discriminate against type of user, for example, licences which prohibit commercial re-use are not allowed. Interviews with civil society advocates and event observations evidence there has been some debate around non-commercial licences, since some OGD advocates perceive a risk of commercial interests appropriating OGD into non-open systems, or corporate profits being subsidised through fully open commercial re-use of data. However, because problems emerge in defining 'commercial', restrictions can lead to licence interoperability issues which restrict innovation, and there are concerns that non-commercial terms could restrict emergent 'open' production models, most OGD advocates have tended to agree to commercial re-use despite their concerns. Although the Open Definition prohibits non-commercial terms, share-alike clauses are sanctioned. Data owners can therefore apply share-alike conditions to stipulate that re-users should apply a compatible licence on any derivatives or modifications to the original, thus going some way to prevent appropriation into non-open systems.

The civil society networks that make up the OGD community are complex and engaged at different levels both with one another, the state, public bodies and the business community. The literature around OGD suggests civil society advocates are drawn from a number of domains, including open knowledge activism (OKFN & Access-Info, 2010), transparency/right to information activism (OKFN & Access-Info, 2010; Davies, 2010), PSI re-user businesses (Davies, 2010), and the linked data/semantic web community (Tinati et al, 2011). Interviewees from all categories highlighted that some of these civil society networks have been engaged in the field of information policy since at least the 1980s. This is particularly the case amongst private sector re-users of PSI who use public data to develop products and inform business processes, and transparency campaigners engaged in the push for access to government and environmental information. Over the years, individuals from these networks have taken up positions both advising, and directly employed within, the state (Interviews: Core Civil Society & Civil Service). This historical context to OGD is something that some more recent advocates are not always aware of, and tensions occasionally surface as a result. As one advocate stressed, "the Open Data crowd sometimes don't see what has been going on out there... So, they come up with ideas that could be problematic - like this thing of saying let's release all the data" (Interviews: Peripheral Civil Society).

A number of further characteristics can be drawn from civil society interviews and observational data. It is difficult to define the community politically; advocates are drawn from across the political spectrum, including liberals, social democrats, conservatives, neo-Marxists, libertarians - left and right, apolitical, and so on. What tends to draw this disparate group together is a tendency to advocate some form of enhanced citizen participation and empowerment with respect to the state and/or corporate power, and/or an interest in digital innovation. For many, therefore, OGD is not an end in itself, it might simply be a needed input into a new product or the first step towards the Semantic Web, whereas for others it is necessary for some broader social end, whether radical or reformist. Whilst some advocates are traditionally employed e.g. as academics or journalists, many are developers or consultants either independent or linked to an OGD related organisation or project. These organisations are funded through a range of means including consultancy and service provision, but also through public digital innovation funds and competitions aimed at promoting innovation for economic and social ends. Many individuals are engaged with the initiative on a voluntary basis, although a small number are employed directly by OGD organisations. At least one individual is funded by a philanthropic organisation, in this case, The Shuttleworth Foundation, a Foundation founded by South African entrepreneur Mark Shuttleworth which invests in promoting social change through funding individual "change agents" working on innovative, open knowledge projects (Shuttleworth Foundation, n.d.).

At a national level the social background of core OGD advocates tends to be elite: highly, often elitely, educated white men from the higher social classes. Local networks are more socially mixed, although white males still significantly dominate. The more peripheral or less public, the more socially mixed appears the community; however, it would still be accurate to describe it as a community with significant social privileges. A sense of disquiet about the social and gender makeup of the community does emerge in interviews and informal discussions with some peripheral civil society advocates, and at times this appears attuned to a wider sense of unease about class and gender relations in the UK. To categorise the civil society OGD community active within the UK in terms of national borders is slightly misleading, since a significant proportion of those engaged are not UK nationals, and the community has significant cross-border engagement within the EU and beyond.

Whilst the 'Open Government Data' initiative has only emerged publically over the last two or three years, the object of this policy initiative datasets produced or owned by public sector bodies and the governance and ownership of such datasets, has been under the scrutiny of civil society actors, including the business community, since at least the 1970s. The data that OGD advocates are interested in, and want opened for anybody to use, re-use and re-distribute, tends to be quantitative datasets (OKFN & Access-Info, 2010), examples of which include geospatial, statistical, environmental, organisational, transport, spending, cultural, archival, and company data. Some of these already exist as datasets that can be re-used although possibly at a prohibitive cost e.g. mapping data, whilst some are data that have not previously been re-usable including some that have not yet been universally digitised. An example of this latter category is data on allotments, which are small plots of land for individual cultivation at low rent, which local authorities in the UK have a legal duty to maintain 'adequate provision' of relative to demand.

The National Archives estimates that 15-25% of information products and services currently depend on re-use of such public sector information (PSI) (The National Archives, 2010). PSI re-users have traditionally had to licence datasets for re-use from public bodies, and whilst some of these have been provided free of charge, many valuable datasets such as those produced by Trading Funds (e.g. mapping and meteorological data) have attracted charges above marginal cost. It is the OGD initiative's focus on democratising re-use of this key economic resource through 'open' licensing that brings it into the socio-economic domain, rather than being understood primarily as a technical or 'computerisation movement' (Kling & Iacono, 1988), or a more rights-based access to information movement. Whilst the recognition that the socio-economic aspect is core to OGD is not always apparent amongst some advocates, it is by analysing the initiative through this lens that an understanding of the deep-seated social struggles that OGD connects with is able to emerge.

Through positioning OGD as a socio-economic initiative with an interest in publically funded datasets, it becomes imperative to contextualise its emergence within the broader field of the political economy of valuable public datasets that has evolved over the last 30-40 years.

The growing commercialisation of information has been a cornerstone of the capitalist economy over the last thirty years within both the private and public sectors. As Burkert (2004) argues, PSI only emerged as a policy issue in the 1970s when ICT developments allowed the separation of information from the processes that generated it, discussions developed about the extent of state functions, and scrutiny of state secrecy began to grow. The business model for PSI tends to be sales of large datasets and information products to both public and private sector organisations. An Office of Fair Trading survey estimates that 78% of these sales are of refined (value-added) data (OFT, 2006, p. 75). It is further estimated that of those businesses that purchase PSI (unrefined and refined), 28% are using PSI to create consumer products, 44% to create products for industry, and 39% for their own business purposes (OFT, 2006, p. 28-9).

Neoliberal restructuring of the UK's public sector began in the 1980s through the privatisation of public assets and marketisation of public services. During this period public bodies came increasingly to look to their informational assets to generate revenue, to sustain themselves as direct public funding was reduced, and to provide a protective barrier from competitors in increasingly liberalised markets. Ordnance Survey (the UK's mapping agency), for example, whilst always having charged for its datasets was subject to increasing government mandated commercialisation since 1983 culminating in its 1999 change of status into a self-funding Trading Fund (Evans, 2006). Similarly, the Postcode Address File, which the Royal Mail owns and manages, grew into a valuable public asset as mail delivery was liberalised (Postal Services Commission, 2006). Selling both unrefined PSI and value-added information products became an important source of revenue for data rich public bodies. Businesses were willing to pay to secure re-use of PSI to build their own, sometimes competing, value-added products and services, to use infrastructural data (e.g. mapping data) in their own systems, and to perform market research. Further, as the demand for digitalised access to data has grown, public bodies have entered into digitalisation contracts with private companies that have then claimed Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) on the lucrative digitalised data. The digitisation of genealogical data held by The National Archives is a key example.

However, the growing commercial exploitation of PSI did not simply boost the reserves of public bodies. As the government privatised public assets and encouraged the outsourcing of public services, datasets needed by public bodies became increasingly owned or managed by private interests that extracted profit by selling data back to public authorities or demanding payment to undertake data retrieval. Further, data and information that was previously shared openly between public bodies became restricted as newly privatised organisations went into competition with one another, and data markets emerged within the remaining, but increasingly commercialised, public sector with data 'owners' charging other public sector bodies for re-use. Such markets could make up a substantial proportion of the data owner's revenue; however, data pricing policies often led to data/information deficits in cash-starved public bodies, potentially contributing to reduced innovative capacity and responsiveness.

The liberalisation agenda also brought increased scrutiny of public sector bodies' anti-competitive practices. Public bodies whose 'public task' was to collect and manage key datasets, were expected to compete in the market on the same terms as private competitors in the field of 'refined' products and services. Increasingly, public bodies came under pressure to provide key 'unrefined' data sets at marginal cost (generally zero for digital goods) in an effort to promote an innovative and competitive market for PSI re-use.

Set within this broader context some public bodies feel threatened by aspects of the emergent OGD initiative and the support it has received from some within the state. Further, in the context of large scale public sector cuts any threat to an institution's revenue stream is going to be looked upon by some with suspicion. Whilst Peled (2011) argues that the "passive-aggressive" attitude of some US public agencies to the USA's OGD programme is the result of the value of data in inter-organisational power politics, such an analysis is reductive in scope since it decontextualises organisations and individuals from deeper structural processes. An understanding of the political economy (accounting for both material and ideational factors) of valuable public data adds a deeper layer of analysis when questioning why OGD advocates can sometimes face entrenched resistance from within public bodies to their proposals to make data flow. With this context in mind, the article will now move on to consider recent developments aimed at opening up 'unrefined' and 'raw' public data for all to re-use at marginal cost.

There is significant cross party support for OGD in the UK; both the Labour and Conservative parties had commitments to OGD in their 2010 general election manifestos. The initial impetus from the UK government for opening up government datasets for anyone to use, re-use and distribute at marginal cost came under the previous Labour government. Whilst the issue of PSI re-use has been a relatively specialist policy issue for many years, more widespread active engagement with the issue began in the last five years. During this period a number of research studies (Mayo & Steinberg, 2007; Newbery et al, 2008; OFT, 2006) were commissioned or undertaken by government bodies, and in 2009 Tim Berners Lee and Nigel Shadbolt were appointed as government information advisors. These moves culminated in the launch of the data.gov.uk website (January 2010), and the opening up of a number of Ordnance Survey datasets (April 2010). Work also began on the new UK Government Licensing Framework, leading to the new Open Government License, launched in September 2010, which allows anyone to use, re-use and distribute the data it is applied to. However, interest has developed significantly since the change of government to a Conservative-Liberal coalition in May 2010. The new Coalition's 'Transparency Agenda', which is central to a number of major policy and legislative proposals including Open Public Services (HM Government, 2011a), a new Right to Data (HM Government, n.d.), and the formation of a Public Data Corporation (HM Government, 2011b), has OGD at its core.

The formation of the Public Sector Transparency Board in June 2010 was one of the earliest actions of the new government. Chaired by self-confessed OGD "zealot" Francis Maude (Minster of the Cabinet Office), the new Board is comprised of, amongst others, civil society OGD advocates Tim Berners Lee, Nigel Shadbolt, Rufus Pollock (co-founder of the Open Knowledge Foundation and co-author of The Cambridge Study) and Tom Steinberg (Director of mySociety). The publishing of big datasets has also been a priority for the Coalition, with the opening of the Combined Online Information System (COINs) Treasury spending database, all departmental spending over 25,000, and the recent announcements regarding the publishing of significant amounts of NHS, education, criminal justice, transport and public assets data. Central government also mandated local authorities to open up their spending over 500 and executive pay data, and encouraged them, along with other public bodies such as the police and public transport authorities, to open up other datasets under open licenses.

The positioning of OGD under the brand of 'transparency' is itself interesting, and partially masks the underlying political economic context and interests of the PSI industry in OGD policy. The utilisation of the 'transparency' label is politically appeasing in the UK context as it appeals to a widespread public desire for increased transparency and accountability following the MPs expenses scandal in 2009 [3]. However, whilst OGD might potentially support modes of transparent and democratic governance, the current 'transparency agenda' should be recognised as an initiative that also aims to enable the marketisation of public services, and this is something that is not readily apparent to the general observer. Further, whilst democratic ends are claimed in the desire to enable 'the public' to hold 'the state' to account via these measures, there is an issue in utilising a dichotomy between the state and a notion of 'the public' which does not differentiate between citizens and commercial interests. The 'we' in this construct thoroughly displaces the notion of citizens as state ("we are the state") to a 'we' that is a mass of private interests (both individual and commercial) outside the state. The construction of interests that arises here is significant since it shapes the way that people think about how they engage with society, encouraging those attracted to civic engagement into an embrace of solidarity with profit seeking interests, distanced from the ever suspect notion of the state. As with the use of the term 'transparency' to mask the serving of commercial interests, this construction of interests can work to mask the relation between corporate and capitalist-state power within neoliberal capitalism. Whilst this is certainly not a new phenomenon it is one that is still valuable to point out.

If we peel back the cloak of transparency from the UK government's engagement with OGD, a different interpretation of events begins to emerge. Focussing in on the Public Data Corporation, Open Public Service reform, and the effort to define 'the public task' in PSI re-use regulations, the article will now go on to examine ways in which powerful groups within the state are attempting to shape OGD and use it to force broader agendas wrought by an ideological faith in the primacy of markets over social provision.

Interviews evidence that the decision to form a Public Data Corporation (PDC) is a subject of some concern for a range of civil society and some state based (Local Government) OGD advocates. The aim of the proposed PDC is to "bring together Government bodies and data into one organisation and provide an unprecedented level of easily accessible public information and drive further efficiency in the delivery of public services" (Cabinet Office, 2011), and therefore constitutes a significant change in the organisation of PSI production and supply. There is a significant amount of confusion about what specifically the PDC will be and the reasoning behind it, as well as scepticism amongst some civil society OGD advocates that its formation is a good policy decision. The desire of the government for the PDC to be "a vehicle which will attract private investment" (Cabinet Office, 2011) has also been a cause of both apprehension (Interviews: Peripheral Civil Society), with suggestions that a primary motivation could be a push to create an entity suitable for privatisation (Interviews: Civil Service). A number of peripheral civil society interviewees reported that the Transparency Board (perceived by many as the civil society advocates' key connection with the state) has been kept at a distance - consulted, but not listened to - during PDC negotiations. However, some members of the Transparency Board did refute this claim and were content with the level of input the Board had in its advisory capacity. In spite of these issues, some peripheral civil society interviewees reported that through the organisational efforts of the Open Rights Group, a number of advocates were able to meet and discuss the issues and put forward a number of suggestions in the Cabinet Office's PDC public engagement process.

At the point of writing (September 2011) it is unclear specifically what the Public Data Corporation will become. In July 2011, the government moved Ordnance Survey, the Met Office and the Land Registry (three key Trading Funds) under the responsibility of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) in preparation for the formation of the PDC as a self-contained public data organisation within BIS. At present it is the responsibility of the Shareholders Executive (which is also located within BIS) to act in the best interests of the government as a Trading Fund shareholder. However, it is clear is that there are elements of the Shareholder Executive and HM Treasury (the UK's ministry of economics and finance) who are concerned about the OGD model, perceiving risks to state revenue gained through the exploitation of data assets. These concerns, however, are critiqued as "old school" by some within the state (Interviews: Civil Service). Interviews with civil servants evidence that a range of actors within government and the civil service are instead drawn to the conclusions of the state commissioned Cambridge Study (Newbery et al., 2008), which Rufus Pollock (co-founder of the Open Knowledge Foundation, member of the Transparency Board, and key OGD advocate) contributed to. The Cambridge Study argues that the socially optimal policy is for unrefined digital data to be available for re-use at marginal cost (generally zero for digital resources), whilst the charging regime on refined PSI products should remain intact. These refined products, it is argued, would then be in fair competition with other suppliers, since there would be equal access to unrefined data inputs. Such a model, they highlight, also immediately addresses competition concerns raised by the Office of Fair Trading against Trading Funds' re-use of unrefined data (OFT, 2006). In a further paper, Pollock goes on to argue that the optimal charging model would be direct state subsidy or, in some cases, charges to update the database (Pollock, 2008). These economic arguments thus draw heavily on a liberal economic paradigm with strong emphasis on supply-side policies based on removing constraints on commercial production through liberalisation and marketisation, combined with taxpayer subsidisation of infrastructural resources such as data.

Drawing on the conclusions of the Cambridge Study and the earlier PIRA study which first articulated the argument that "eliminating licence fees would produce additional taxation revenues to more than offset the lost income from PSI charges" (PIRA International, 2000, p. 6), some interviewees put forward arguments claiming that an increase in commercial innovation around PSI re-use as a result of easing restrictions on producers would lead to increased tax revenue. However, this claim needs some dissection, something also recognised by a number of peripheral civil society interviewees. Even if liberalisation does promote industry growth, it is more likely that 'islands' of developers and companies would be concentrated in certain cities and countries rather than be spread evenly. There is, therefore, no evidence to suggest that corporate and income tax revenue would enter the Treasury of the state, or business rates to the local authority that paid for the production and supply of the data. This could leave VAT on some new consumer products as the only tax revenue stream that is positively affected. However, the increased competition being created in the production of these consumer goods could also lead to reduced prices, and thus, reduced or unchanged VAT revenue. These potential risks in ensuring a flow of revenue to fund marginal cost supply suggest funding may have to be diverted from other parts of the public sector unless the state uses some other mechanism (e.g. corporate taxation) to increase total revenue which presently seems unlikely, or there is a sudden reduction in required revenue in other areas of the public sector. Further, whilst the UK state might try to incentivise UK based developers and businesses to become first movers in the innovative re-use of OGD through a range of supply-side policies, this does not deal with the pressing issues of tax avoidance and evasion, nor does it address the problematic relation that could ensue between a profitable UK re-use industry that is supplied with free data from states with no or few such businesses to tax.

Whilst these academic reports focus on the specifics of the PSI market, it is important to recognise that there are groups within the state who are ideologically attracted to the conclusions of The Cambridge Study, and are using OGD to push an agenda of marketisation and liberalisation beyond PSI markets (Interviews: Civil Service). As Francis Maude (Minster for the Cabinet Office) articulated, OGD is "what modern deregulation looks like" (Maude, 2010). The Coalition's appropriation of the initiative to ideologically motivated ends emerges most forcefully in their recently released Open Public Services White Paper (HM Government, 2011a). Not only is the title of this White Paper interesting as an apparent attempt at domesticating the notion of 'openness' to something more resembling blanket marketisation of public services, but the paper also states categorically how OGD will underpin this effort. The White Paper proposes that all public services, other than national security and the judiciary, should be opened to competition from the private and third sectors. Further, it argues that OGD is required to give people the information they need to make good choices in their use of public services, and to provide potential competitors with the information they need to challenge the public sector providers. Such information includes "how much services cost to run, the amount providers are being paid, and whether those providers are meeting user needs" (HM Government, 2011a, p. 35), as well as departmental business plans and procurement contracts. The dominant logic within these claims rests on the notion of citizen as consumer and giving private sector competitors access to commercially sensitive information, potentially putting public providers at a significant disadvantage in a marketised system that many citizens do not want. As some OGD advocates have highlighted, this marketisation agenda also risks creating further barriers to transparency in public services. Crucially, access to information is threatened unless accessibility and re-usability of data and information is built into contracts between government and service providers; or, in some cases, unless the cost for the relevant public body to access information from private providers falls within the costs allowed for Freedom of Information requests.

Related to this issue of marketisation of public services, interviews with civil servants and policy research suggests a key issue currently drawing considerable interest from regulators (The National Archives) and other interested bodies is the definition of 'public task' which arises out of the PSI re-use regulations. PSI re-use regulations state that public bodies (with some exceptions) must allow re-use of their information without discrimination or unnecessary restrictions if its production is part of their public task. Whilst the regulations also currently allow charging at above marginal cost, this obviously is of significant interest to the OGD initiative. A key issue is that although the regulations only apply to data which falls within the remit of a public body's 'public task', it is not often directly defined what a public body's 'public task' actually is. The National Archives (TNA) has recently published guidance on the term (The National Archives, 2011), encouraging public bodies to produce statements of 'public task' in advance of any potential complaints under the re-use of PSI regulations. In relation to the current scrutiny and cutting of public services, concerns may be raised about the desire to push public bodies to define their 'public task'. The Advisory Panel on Public Sector Information, in which TNA participate, proposes that there is a "dichotomy between public task in the narrow context of public sector information and information trading, on the one hand, and the broader philosophical issues of public services and national policy on the other...if the project and principles get embroiled in the latter it would be difficult to reach any conclusion" (APPSI, 2011). However, such reductionism in order to more easily reach a conclusion is problematic, particularly when removing the discussion from the context it exists within could provide a backdoor to force the marketisation of public services.

Whilst it is clear that the UK government is attempting to use the OGD initiative to leverage its marketisation agenda beyond the specific PSI re-use market, it is also important to consider the nature of the OGD/PSI re-user business environment. Interviews and observations suggest that some at the periphery of the OGD initiative have tended to conceptualise OGD as being about small start-ups, voluntary 'civic hackers' and other micro/small enterprises. This is unsurprising given the heavy weighting towards micro/small businesses in the UK's IT sector and the large numbers of 'civic hackers' active in the OGD community; however, the potential re-user industry for OGD is broader than this. The PSI re-use industry comprises a range of industries and includes multinational corporations (MNCs) such as Google and LexisNexis, conglomerates such as Daily Mail and General Trust whose DMG Information division is the parent company of the UK based Landmark Information Group, as well as an array of SMEs, micro enterprises, independent developers, and voluntary 'civic hackers'. The focus on key valuable public datasets, as argued above, draws the OGD initiative into the same space as this much broader PSI re-use industry. Whilst there are certainly differences between the data uses and demands of established PSI re-user businesses and the OGD community, it is evident that OGD advocates are also pushing for key datasets that are of importance to key interests within the PSI re-use industry, for example, unrefined Trading Fund and transport data.

The Locus Association represents the PSI re-use industry in the UK, and is a founding member of the PSI Alliance which represents industry interests at the European Union level. These organisations' members are drawn from both UK/EU based companies and multinationals with business interests in the UK/EU. Connecting the Locus Association and the PSI Alliance is Michael Nicholson: the former Managing Director of Intelligent Addressing Ltd - a private firm acquired by the state in 2011; Deputy Chair of the PSI Alliance; former Chair of the Locus Association; and, expert member of the UK government's Advisory Panel on Public Sector Information (APPSI) which he joined shortly after his PSI related complaint against Ordnance Survey was overturned by APPSI in 2007. Whilst Nicholson is perhaps best known in PSI circles for his complaint against Ordnance Survey whilst at Intelligent Addressing, interviews with civil servants and online research suggest he also has a strong network of connections within national government. Further, he has worked alongside key OGD advocates at PSI/OGD events such as the 5th Communia workshop organised by the Open Knowledge Foundation in 2009, where he presented alongside Rufus Pollock (OKFN) and Tom Steinberg (mySociety).

Nicholson's vision is clear: he wants the state rolled back to areas of market failure and statutory requirement, and he wants marginal cost re-use of PSI procured (not collected) by the state to meet its requirements for 'good government' (Nicholson, 2009). Unlike in some industries, the PSI re-users tend to be in alignment in their lobbying approach. As one industry representative stated: the position of businesses represented by the PSI lobby is to stop the public sector competing in the market by pushing for marginal cost re-use and more transparency in licensing conditions in order to ensure a "fair and level playing field" (Interviews: Business Interest).

Whilst the OGD advocates tend to want zero-cost data that is openly licensed, these companies are willing to pay to re-use datasets, albeit at marginal cost, and they want licenses or contracts that guarantee their supply (Interviews: Business Interest). The PSI re-use industry is engaged in developing a wide range of products for both business and consumer markets often utilising high level skills to work with complex datasets such as legal, geographical, and business data. Whilst the uses of PSI are numerous, there are a number of industry developments that are worth outlining and considering in relation to broader social ends: Google's Public Data project, financial market interest in weather data, and the Smart Cities initiatives.

Google, a member of the PSI Alliance and regular participant at OGD events, is currently developing its Public Data Explorer project. As part of its mission to "organise the world's knowledge", Google has expanded its range of services into the field of organising the world's public data, making it universally accessible and usable (Yolken, 2011). As a result of its acquisition of Swedish non-profit GapMinder's Trendalyzer data visualisation technology in 2007, Google is able to offer a range of interactive visualisations through which citizens and policy makers can explore patterns in public data. In this sense they are partially aligned with elements of the OGD community, including data journalists, advocating for data re-usability for democratic reasons. However, of particular concern here is the risk of monopolisation of data interpretation by companies such as Google through the use of seemingly high quality and easy to use interpretive tools whose inner processes are closed to analysis. Some civil society interviewees raised this issue of closed-source analysis tools as a potential problem, although others dismissed the concern arguing that competitive economic processes should counter any monopolisation threat.

The financial markets are also interested in PSI in order to develop new products. Lloyds of London, along with others, are lobbying to have their position in the market for meteorological data improved in order that they are better placed to develop insurance products around extreme weather events (BERR, 2008): a potentially lucrative site for investment as climate change takes hold. Weather derivatives (hedging business ventures against the weather) were also highlighted by an interviewee as another area of potential expansion (Interviews: Civil Service). Popular in the USA and traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, an exchange well known for its 'innovative' derivatives and futures trading, it is not currently possible to develop such financial products in the UK market due to the lack or high cost of meteorological data which is collected by the Met Office. What must be questioned here is the extreme inequity inherent in a system whereby protection from a societal problem such as climate change is offered on an individual, rather than social, basis to those that are able to afford protection. Further, it should be questioned whether the development of markets that aim to exploit, rather than resolve, the growing risk and instability in our weather systems is socially beneficial.

A further development, and one that is related to the concern over Open Public Services, is the emergent Smart Cities projects. Whilst many independent and civic developers have taken advantage of open public transport data, the significant issue in this field is in relation to further corporate takeover of the infrastructural systems that urban services and utilities are based upon. As The Future of Cities, Information and Inclusion report states, in a section labelled "Battle for the Smart City":

Managing rapid urban growth and global warming will give rise to a multi-trillion dollar global market for smart cities and infrastructure...Industry leaders will have clear visions for the growth of citiesand will promote those agendas with city officials." (Institute for the Future, 2010)

Whilst this is billed as a 10-year forecast it is already a present reality in the UK with MNCs' (e.g. Cisco, IBM, and Oracle) Smart City visions receiving favourable appraisal from some state based interviewees. These MNCs are keen to take over and develop new 'Smart' integrated urban infrastructures, such as public transport systems. In order to develop such systems they need access to and the ability to integrate the same types of databases that independent developers and 'civic hackers' are pushing to get opened. There is therefore a significant risk of corporate monopolisation of the shaping of urban infrastructures, something which, among other issues, risks profit seeking, rather than sustainability and local governance, shaping their development.

These examples are not intended as arguments against opening up data, since there is little doubt that such corporations could gain access to and re-use of this data anyway if it was deemed beneficial by the government, and this would potentially be at a cost unaffordable to independent developers and citizens thus leading to even greater corporate monopolisation. What is argued, however, is that it is necessary for OGD advocates to be aware of, engage in critical discussion about, and act in response to this broader environment that they are working in.

Whilst the OGD community is not a homogenous mass interviews with civil society advocates and observations evidence significant divergences in contextual awareness, strategy and politics within the community some generalisations can be made. Whilst many within the OGD community are engaged in developing OGD tools and products for business, civic and personal reasons, interviews indicate many also have some philosophical or socio-political reasoning behind their engagement in an 'open' initiative. As stated above, many have a high commitment to civic principles and draw on a range of normative concepts which motivate their activity, including concepts such as freedom, justice, equality and the commons. Interviews suggest that many advocating for OGD are still shaping their understanding of the environment they are working within. What is crucial to understand at this point is how aware are advocates of the context they are engaged in, what response does the community have to this situation, and are OGD advocates vulnerable to co-optation by dominant interests? Key issues that emerged in interviews and which will now be examined are contextual awareness, sidelining of critique, and meritocratic governance.

Interviews suggest that the awareness of the broader context outlined above within the OGD community is quite limited. Whilst there are some advocates that are broadly aware of the context of OGD in relation to the PSI re-user community, there are many that are not. Further, in relation to Coalition policy the awareness of how OGD is being used to push forward a marketisation agenda is very limited. Rather, advocates often contextualise OGD in terms of transparency, participation, innovation, and countering information asymmetries by reclaiming public data from monopoly capture (whether public or private). A number of factors emerging from interview and observational findings can help explain these patterns. Many advocates, as is to be expected, are simply drawing on hegemonic liberal logic of consumer choice, freedom, competitiveness, innovation etc and framing their resistance to forms of dominant power within its borders. Further, the action orientation of much of the community can displace it from consideration of broader contextual issues, as can a tendency towards compartmentalisation in problem solving, possibly drawn from a programming logic that emerges within sections of the community. Further, there is a significant issue regarding the sidelining of critical discussion in favour of prioritising getting the data opened, and there is concern from some advocates that critical discussion could be further limited by the restrictions on those individuals and groups who have been drawn closer to the state through advisory roles and contracted provision of products and services.

Whilst in recent months some critiques have begun to emerge publically at the edges of the community [4], the tactic of putting off dealing with critical discussions is one that has emerged relatively strongly in interviews with civil society advocates that are aware of some of the key issues. The priority, it is argued, is to get data opened, and then, once this is achieved, deal with any problems. Whilst the logic behind this pragmatic approach is perhaps understandable for those focussed on opening up data, it also poses a number of significant issues. Firstly, it stifles critical understanding within the broader OGD community, leading to the possibility of politically naive interpretations of OGD becoming increasingly dominant. Secondly, it detracts critical attention from those within the community that are supportive of this broader marketisation agenda. Thirdly, there is a sense of elitism in how norms are being established not to address key issues within the broader community, a process that will result in some advocates being divested of the opportunity to develop a deeper understanding of that which they are fighting for. Finally, it can lead to community insularity as those on the outside that could complement its work potentially begin to perceive it as politically naive and thus decide not to engage.

A further issue that emerges is in relation to the 'meritocratic' mode of governance within the community, something which is explicitly referred to in the Open Knowledge Foundation's governance principles (OKFN[2], n.d.) and which is also observable in practice. As an initiative that is engaged in high level policy and legislative changes and in some cases an attempted remodelling of state-citizen relations, concerns do sometimes arise towards the periphery of the movement about how this mode of governance functions. Governance concerns emerging from interviews and informal discussions with more peripheral advocates highlighted a number of concerns including a lack of democratic decision making and a sense of a socially elite, masculine, and technologically driven model of 'merit'. Further, attempts to engage the community with these concerns sometimes blatantly, sometimes more subtly - often faltered, either being ignored or not being prioritised by the community. It is also apparent from interviews that the broader community is very unclear about what specifically the political positions are of those advocating on behalf of the community to the state, particularly in relation to their views on the role of the state and the public sector. This is a crucial issue given the context, and one that some advocates will not be aware of given lack of contextual awareness. Since there is no democratic governance and a lack of public discussion of relevant issues within the community, there sometimes emerges a strong sense of disconnect between the broader community and its 'representatives'. This is problematic, and betrays an elitism that makes the community vulnerable to assimilation into others' agendas. Further, whilst there are a number of individuals that are actively engaged in progressive activity outside of OGD and trying to bring the two together in various ways, the OGD community as a whole is quite isolated from the wider public relative to its relationship with those in positions of power. This is something which deepens the sense of elitism and leaves the OGD community vulnerable to reproducing a top-down mode of governance.

Drawing on interviews and observations it is apparent that whilst there are certainly people engaged within the OGD community that would highlight similar issues, they are not the majority. There is a sense that significant sections of the community are limited in their ability or desire to engage a deep appreciation of the complex social inequalities that OGD has emerged, and will evolve, within. Amongst some more politically and socially aware advocates concerns have therefore arisen that these issues combine to make the community "politically a bit naive at some points" (Interviews: Peripheral Civil Society) and vulnerable to co-optation by elite interests.

In summary, there are significant social and political stakes being played for in the shaping of OGD in the UK. Whilst some of the more politically aware data activists have taken a strategic line of downplaying potential risks and issues in order to push the OGD agenda, there has been significant co-optation of the initiative into an ideologically framed mould that champions the superiority of markets over social provision. As the most vulnerable in society are facing substantial public spending cuts, the OGD model risks being interpreted as, and potentially becoming, little more than a corporate subsidy. The continuing scandals that have surfaced from the UK's political classes over the last two years, combined with the broader socio-economic and political context, should make anyone sceptical of the current administration's cloaking of this initiative under the veil of transparency and participation. These factors combine to point towards a process of co-optation and closure rather than opening.

In spite of these problems, it cannot be argued that OGD is the cause of this broader context. Further, the supply-side push is towards a model of open means of production within this sector, and the initiative has the potential to create a supply of data that is also required for more progressive political projects. It is important in the final analysis of OGD, therefore, to ask the following questions: is there more or less social benefit to be gained from resisting OGD entirely and restricting information flows and information interpretation through inducing false scarcity? And, does OGD open up possibilities for a progressive future based on socially and politically egalitarian principles that takes us beyond these immediate concerns?

It is difficult to make a (non-reactionary) argument against the free flow of data and information, however, it is crucial to understand the implications of co-opted partial approaches to openness, particularly if they risk weakening public institutions already under significant political and market pressure. As the above discussions of the social and political interests engaged in shaping OGD indicate, a progressive future for OGD based on egalitarian principles is not guaranteed. The emergence of OGD in the UK at this specific time should be recognised as being the result of converging pressures and interests. To observe this process in an overly fragmented way opens up progressive civil society advocates to significant vulnerabilities. The shaping of OGD is a political and social struggle. Failure to engage in this context does not make it apolitical; it simply creates a vacuum for vested interests to harness the power of OGD for private gain. If there is any potential in shaping OGD towards a progressive future, this struggle must be widely appreciated and understood and it must engage those beyond the current OGD community. In particular, the following recommendations are made that community informatics practitioners and researchers might work with:

APPSI. (2011). Minutes from the Advisory Panel on Public Sector Information meeting 1st March 2011. London: The National Archives. Retrieved July 10, 2011 from http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/meetings/010311APPSI-Meeting-Minutes.pdf

Benjamin, S. et al. (2007). Bhoomi: "E-Governance", Or, An Anti-Politics Machine Necessary to Globalize Bangalore? Retrieved September 14, 2010 from http://casumm.files.wordpress.com/2008/09/bhoomi-e-governance.pdf

BERR. (2008). Supporting innovation in services. Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform: London.

Burkert, H. (2004). The Mechanics of Public Sector Information. In G. Aichholzer & H. Burkert (Eds.), Public Sector Information in the Digital Age (pp. 3-22). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Cabinet Office. (2011). Public Data Corporation to free up public data and drive innovation. Retrieved January 15, 2011, from http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/news/public-data-corporation-free-public-data-and-drive-innovation

Davies, T. (2010). Open data, democracy and public sector reform: a look at open government data use from data.gov.uk. Retrieved September 3, 2010 from http://practicalparticipation.co.uk/odi/report/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/How-is-open-government-data-being-used-in-practice.pdf

Evans, A. J. (2006). The National Geographical Information Policy of Britain National Policy/: 1746 - 1999. GIS Korea 2006: Proceedings of the GIS International Conference Korea 2006, 275-299. Retrieved July 20, 2011 from http://www.geog.leeds.ac.uk/papers/06-1/06-1.doc

Gurstein, M. (2011). Open data access vs. open data (effective) use. First Monday, 16(2). Retrieved June 1, 2011 from http://www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3316/2764

HM Government. (2011a). Open public Services White Paper. The Stationary Office: London. Retrieved July 24, 2011 from http://files.openpublicservices.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/OpenPublicServices-WhitePaper.pdf

HM Government (2011b). Plans for a Public Data Corporation. Retrieved July 24, 2011 from http://pdcengagement.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/pdc/

HM Government. (n.d.). Protection of Freedoms Bill. Retrieved March 21, 2012 from http://services.parliament.uk/bills/2010-12/protectionoffreedoms.html

Institute for the Future. (2010). The Future of Cities, Information and Inclusion. Retrieved July 24, 2011 from http://www.iftf.org/inclusion

Kling, R., & Iacono, S. (1988). The Mobilization of Support for Computerization: The Role of Computerization Movements. Social Problems, 35(3).

Longo, J. (2011). #OpenData: Digital-Era Governance Thoroughbred or New Public Management Trojan Horse? Public Policy and Governance Review, 2(2).

Maude, F. (2010, November 19). Presentation at the International Open Data Conference, Wellcome Trust, London.

Mayo, E., & Steinberg, T. (2007). The Power of Information/: An independent review. OPSI: London. Retrieved July 10, 2010 from http://www.opsi.gov.uk/advice/poi/power-of-information-review.pdf

Newbery, D. et al. (2008). Models of Public Sector Information provision via Trading Funds. Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform: London. Retrieved July 30, 2010 from http://www.berr.gov.uk/files/file45136.pdf

Nicholson, M. (2009, March 26). PSI/: State Control or Public Freedom? Paper presented at the 5th Communia Workshop. London. March 26 2009. Retrieved on July 12, 2011 from http://www.communia-project.eu/communiafiles/ws05s_MJLNicholson.pdf

OFT. (2006). The commercial use of public information (CUPI). London: Office of Fair Trading. Retrieved July 27, 2010 from http://www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/reports/consumer_protection/oft861.pdf

OKFN & Access-Info. (2010). Beyond Access/: Open Government Data and the 'Right to Reuse'. Retrieved September 14, 2010 from http://www.access-info.org/documents/Access_Docs/Advancing/Beyond_Access_7_January_2011_web.pdf

OKFN[1]. (n.d.). Open Definition: defining the open in open data, open content and open services. Retrieved May 2, 2010 from http://www.opendefinition.org/okd

OKFN[2]. (n.d.). Governance. Retrieved July 2, 2011 from http://okfn.org/governance/#meritocracy

OSI. (n.d.). The Open Source Definition. Retrieved June 23, 2010 from http://www.opensource.org/docs/osd

Peled, A. (2011). When Transparency and Collaboration Collide: The USA open data program. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, (Early View). Retrieved on August 23, 2011 from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/asi.21622/pdf

PIRA International. ( 2000). Commercial exploitation of Europe's public sector information. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg

Pollock, R. (2008). The economics of public sector information. Working Paper, University of Cambridge, Cambridge. Retrieved on July 30, 2010 from http://rufuspollock.org/economics/papers/economics_of_psi.pdf

Postal Services Commission. (2006). Postcomm's proposals for the future management of the PAF: a consultation document. London: Postal Services Commission. Retrieved July 24, 2011 from http://www.psc.gov.uk/documents/1237.pdf

Shuttleworth Foundation. (n.d.). Shuttleworth Foundation. Retrieved September 14, 2011 from http://www.shuttleworthfoundation.org

The National Archives. (2010). The United Kingdom Report on the Re-use of Public Sector Information 2010. London: The National Archives. Retrieved April 11, 2011 from http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/psi-report.pdf

The National Archives. (2011). Guide to drawing up a statement of public task. London: The National Archives. Retrieved 24 August, 2011 from http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/information-management/guide-to-drawing-up-a-statement-of-public-task.pdf

Tinati, R. et al. (2011). Exploring the UK Open-PSI Community. Paper presented at the SharePSI: Removing the roadblocks to a pan European market for Public Sector Information re-use conference, Brussels, 9-10th May, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2011 from http://eprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/22293/

Wright, G. et al. (2010). Report on Open Government Data in India. Centre for Internet and Society: Bangalore. Retrieved March 14, 2011 from http://www.cis-india.org/openness/publications/ogd-report

Yolken, B. (2011, July 1). Google Public Data: Enhancing Data Discovery and Exploration. Paper presented at the OKCon 2011: Open Knowledge Conference, Berlin, 30 June - 1 July 2011.

[1] Francis Maude (Minister for the Cabinet Office, UK Government). Presentation at the International Open Data Conference, Wellcome Trust, London, November 19 2010

[2] Public Sector Information is generally divided into two categories. Distinctions that draw on notions of market failure, public goods and competitive markets tend to use the 'unrefined' versus 'refined' or 'upstream' versus 'downstream' distinction. The Office of Fair Trading (2006, p. 53) proposed that PSI is 'unrefined' if the public authority is the sole supplier of data as it would be uncompetitive to produce it commercially, whereas PSI is 'refined' if its supply would attract competition in the market. Pollock (2008, p. 7) similarly argues 'upstream' information cannot be sourced from anywhere other than the public body, whereas 'downstream' information could be provided by another organisation if that organisation had access to the relevant 'upstream' information. An earlier categorisation (proposed in 2000 by the Treasury) is based on the reasons for data collection and processing. Here, 'raw data' and 'value-added information' are used to highlight the distinction between data that are collected because they are central to government's core responsibilities ('raw data'), whereas information is 'value-added' when the use value of 'raw data' has been enhanced through, for example, manipulation, analysis, summarisation, and making it easier for end-users to use (Newbury et al, 2008, p. 10). These distinctions are therefore crucial to policy, and further research into their development would be beneficial.

[3] The 2009 MPs expenses scandal resulted from the release of information which evidenced the widespread abuse of the allowances and expenses Members of Parliament were entitled to claim. The Wikipedia article on the topic provides a good overview: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Kingdom_parliamentary_expenses_scandal.

[4] See the 'Challenging Openness' session in May 2011 at the FutureEverything Conference in Manchester (http://vimeo.com/25652682) and a small number of presentations at the Open Knowledge Conference in Berlin, June 2011 e.g. Chris Taggart, 'Global open data: a threat or saviour for democracy?' (http://vimeo.com/26390698) and Michael Gurstein, 'Open Data Louder Voices?' (http://vimeo.com/26414945)