Can The NINTENDO WIITM Sports Game System Be Effectively Utilized In The Nursing Home Environment?

Keogh, J.W.L.1,2, Power, N.3, Wooller, L.2,4, Lucas, P.4 & Whatman, C.4

1 Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Australia

2 Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition Research, AUT University, Auckland, New Zealand

3School of Interprofessional Health Studies, AUT University, Auckland, New Zealand

4 School of Sport and Recreation, AUT University, Auckland, New Zealand

Introduction

The population is aging in many developed countries, with this predicted to involve a disproportionately large increase in those aged over 80 years (Shalala, Satcher, Koplan, & Sondik, 1999). As the age-related decline in independence and functional ability become greater after 80 years (Frontera et al., 2000), many more older adults may require aged care services and ultimately move into nursing (rest) homes. Although nursing home staff strive to provide a nurturing, caring and stimulating environment for their residents, many nursing home residents may not perform sufficient physical and social activities to maintain their health and wellness (Brown, Allen, Dwozan, Mercer, & Warren, 2004; Nelson et al., 2007).

Many studies have sought to examine the benefits of a variety of physical and social activities for older nursing home residents (Brown et al., 2004; Fiatarone et al., 1994; N. L. Hill, Kolanowski, & Kurum, 2010; MacRae et al., 1996). While a variety of physical (e.g. muscular strength and endurance, mobility and walking speed) and psychosocial (e.g. quality of life, loneliness and social integration) benefits were reported, there can be many barriers preventing the performance of these activities in nursing homes. Such barriers may reflect the lack of time the nursing home staff have to lead such activities, management’s reluctance to pay additional money to external qualified instructors for exercise or art classes, environmental constraints relating to the space and equipment required or perceived (or real) concerns regarding resident safety (Chen, 2010; McKenzie, Naccarella, & Thompson, 2007).

Therefore, cost, space and time-effective strategies allowing more opportunities for nursing home residents to engage in physical and social activities are warranted. Several information and communication technologies (ICT) may help address this problem (Hedström, 2007). Although ICT developments and marketing have traditionally focused on younger e.g. adolescent and young adult segments of the population, advances in the accessibility and the reduced price of ICT mean that various sub-groups of older adults may now access these ICT (Burmeister, 2009, 2010; Hedström, 2007; Shankar, 2010). One type of ICT-like device that has been suggested to offer physical and psychosocial benefits akin to more traditional forms of physical activity for a variety of inactive or disabled groups are active video games like the Nintendo Wii SportsTM (NWS). These games can be played standing or sitting and involve a hand-mounted controller to perform simulated sporting movements. Evidence exists that indicate these active video games require significantly more energy expenditure and levels of physical activity than regular video-games or watching television (Epstein, Beecher, Graf, & Roemmich, 2007; Graves, Stratton, Ridgers, & Cable, 2007; Maddison et al., 2007; Unnithan, Houser, & Fernhall, 2006). These games would also appear to require the integration of sensory and motor systems, require both fine and gross-motor control and (in some games) the ability to quickly respond to what is observed on the television screen.

There are now many anecdotal reports of the NWS being promoted as a form of physical activity for older adults in countries like Australia, the USA and the United Kingdom, with a small number of studies investigating their benefits. The paucity of peer-reviewed literature indicates the NWS can significantly reduce depressive symptoms and improve health-related quality of life and cognitive performance in community-dwelling older adults. Trends for improved physical function as assessed by muscular strength, sit to stand and 10 m gait speed tests were also observed (Rosenberg et al., 2010; Vestergaard, Kronborg, & Puggaard, 2008; Wollersheim et al., 2010). Two case reports involving nursing home residents; an 89 year old female with an unspecified balance disorder and a history of multiple falls (Clark & Kraemer, 2009), and an 89 year male stroke survivor (Drexler, 2009) have also reported positive effects. These case studies reported that therapist-supervised NWS play over the course of several weeks resulted in substantial improvements in balance (Clark & Kraemer, 2009) and fine-motor control of the stroke-affected upper limb (Drexler, 2009). A qualitative study by Higgins and colleagues (2010) also highlights some of the benefits of the NWS. Higgins et al. (2010) interviewed one staff member from each of the 53 high and low-dependency care centers (including nursing homes, personal care, respite care and therapy centers) using the NWS for 3-6 months. The views of the staff in these centers were generally positive, with purported benefits of the NWS including physical activity and mobility, social interaction, self-esteem and connection with former self.

Of particular interest to this pilot study are older adults living in nursing homes. These individuals may have poorer health and functional ability as well as less opportunities for socialization and ICT access than many other demographic groups (Newman, Biedrzycki, & Baum, 2010; Peri et al., 2008; Van Leuven, 2009). Further, the possible benefits of the NWS for nursing home residents are poorly understood with only two quantitative case studies and one qualitative study conducted in this area to date. The purpose of this pilot study was to examine three separate, but complementary questions regarding the potential use of the NWS in nursing homes. These three questions focused on: 1) documenting self-selected patterns of NWS use by nursing home residents; 2) determining the effect of the NWS on the residents’ dynamic balance, health-related quality of life (QOL) and fear of falling; and 3) using informal conversations to obtain staff and participants’ views on the feasibility and benefits of using the NWS system in the nursing home context.

Activities were done in a community setting, with nursing home staff and residents in a group or community. The benefits of technology use in a group or community setting are used for added benefit'

Methods

Design

A quasi-experimental mixed-methods design involving an experimental and no control group was used in this study. Quantitative data was obtained using log books to assess the residents’ self-selected patterns of NWS play; and through pre- and post-intervention testing, the effect of this NWS game play on the residents’ dynamic stability, health-related QOL and fear of falling. Qualitative data was also obtained from field notes made by members of the research team throughout the course of this pilot study.

Participants

A sample of 11 older adults (5 males and 6 females) with a mean age of 81 ± 6 years living in one nursing home in Auckland, New Zealand gave written informed consent to participate in this study. These residents were approached to participate in this study based on nursing home staff’s recommendations, as the staff believed that all of these individuals had sufficient physical and cognitive ability to successfully use the NWS. All residents had to be > 70 years of age, have sufficient dexterity to manipulate the controller and cognitive ability to understand instructions, verbally communicate and complete the questionnaires. The majority of these participants had moderate mobility limitations, with one being a wheel-chair user. Two nursing home staff also participated in this project, with their involvement limited to providing their opinions of the feasibility, benefits and limitations of the NWS in the nursing home context. Ethical approval was granted by the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee.

Intervention

The NWS game system remained at the nursing home for the duration of the five week intervention so that the participants were able to play any of the five games (Baseball, Bowling, Boxing, Golf and Tennis) at any time. This allowed us to gain some insight into the preferred usage of this technology for this population, a question yet to be investigated in the literature. While the participants were encouraged to play these games standing upright, about half of the group did so seated. Participants were also encouraged to perform flowing upper limb movements involving rotations about the shoulder and to a lesser extent the elbow and wrist joints while playing these games. However, as it was still possible to play these games via predominantly wrist joint motion only (Pasch, Berthouze, Dijk, & Nijholt, 2008), many of the participants chose this option. All participants kept a personal log book so to allow quantification of the frequency and duration of each game played per week. A research assistant visited the nursing home for an average of 2-3 hours each day in the first week so to assist the participants and staff to learn how to operate and play the NWS games. She also taught the residents how to complete the NWS usage log book. The length of these visits by the research assistant was reduced over the following weeks, so to facilitate greater independence of the residents and staff in using the NWS.

Procedures

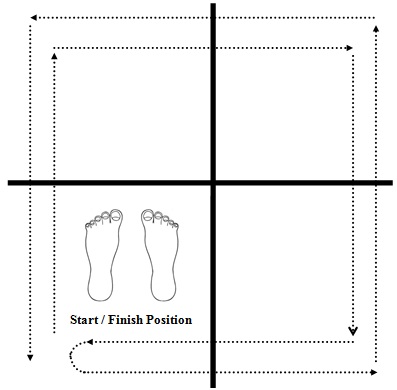

Dynamic Stability: The Four Square Step Test (FSST) was selected as the test of dynamic stability (functional ability) for this study as it has been shown to better predict falls than other common tests including the Timed Up and Go, Step Test and Functional Reach Test (Dite & Temple, 2002) and have excellent test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.93-0.99) (Dite & Temple, 2002; Whitney, Marchetti, Morris, & Sparto, 2007). The FSST required the participants to step over four pieces of foam (each ~ 1m long) that are laid on the ground at 90° angles to each other (like a “plus” sign) (Dite & Temple, 2002). Participants started in a standing position in one square facing forward, and are asked to keep facing the same direction for all eight steps. They were then required to move clockwise around the “plus sign” by moving forward, to the right, backward and then to the left (i.e. returning to the starting square). At this point, the participants reversed their path and moved in an anti-clockwise direction back to their starting position. A schematic of this test is provided in Figure 1. Three trials were performed with the mean of the best two used for statistical analysis.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the FSST (adapted from Whitney, 2007).

The position of the feet relative to the two large bold lines that represent the canes indicates where the participant begins and finishes the FSST. As the dashed lines indicate, the participant begins the FSST by stepping forward, laterally to the right, backwards and laterally to the left, which positions them back at the starting position. From there, they go in the opposite direction back to the Start / Finish position.

Health-Related QOL: Health-related QOL was assessed by the SF-36. The SF-36 is a validated and very commonly used questionnaire to assess the physical and mental health-related QOL of older adults (McHorney, Ware, & Raczek, 1993). The 36 questions of the SF-36 allow the calculation of eight scales scores that ultimately produce two summary scores (physical and mental) health-related quality of life, respectively. Only these two summary scores will be used in this study. The SF-36 exhibits high reliability (ICC = 0.65-0.92) across all scale and summary scores. Its validity is demonstrated by its ability to distinguish between frail and non-frail older adults (Masel, Graham, Reistetter, Markides, & Ottenbacher, 2009) and to be sensitive to change in older adults living in residential care as a result of physical activity interventions (Peri et al., 2008).

Fear of Falling: Fear of falling was assessed by the Modified Fall Efficacy Scale (MFES) (K. D. Hill, Schwarz, Kalogeropoulos, & Gibson, 1996). The MFES has been shown to exhibit very high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.95) and to have very high retest reliability (ICC = 0.93) (K. D. Hill et al., 1996). The validity of the MFES has been demonstrated by the significant differences between healthy and frail frequent older fallers (K. D. Hill et al., 1996). All of MFES questions asked the participant “How confident/sure are you that you do each of the activities without falling” for a different activity. Each of these questions was scored out of 10, with a 1 being “Not confident at all of not falling over” and a 10 being “Confident of not falling over” (K. D. Hill et al., 1996; Tinetti, Richman, & Powell, 1990). The mean score of all questions was then used as the outcome score, so that a score of 1 indicated a very high fear of falling and a score of 10 no fear of falling.

Nursing Home Staff and Residents Comments

The views of key staff who worked closely with the residents and participants were obtained in the final weeks of the study. This was done to gain some feedback on their observations of the possible benefits, safety issues, barriers and motivations to use the NWS in the nursing home context. Staff were also asked for their thoughts and experiences of managing the NWS within their working environment. This included recruitment of suitable participants and the practicalities of housing the equipment. Feedback was elicited in a conversational manner with the aim of putting the participants and staff at ease. Participants discussed their experiences with a member of the research team (NP), whilst the two primary staff members involved in the management of the NWS spoke to the research assistant (LW).

Statistical Analysis

An intention to treat analysis was conducted for all quantitative data, whereby all participants who enrolled in the project were included in the pre- and post-test analyses. Group means and standard deviations were calculated for all quantitative variables relating to NWS usage by the residents as well as the effect of the NWS play on the measures of dynamic balance, health-related QOL and fear of falling. The effect of the NWS intervention on the quantitative outcome measures was assessed with paired T-tests (with unequal variance) and Cohen effect sizes (d). Statistical significance was achieved when p < 0.05. The feedback from the participants and staff was recorded in field notes. These field notes provided the basis from which themes were derived.

Results and Findings

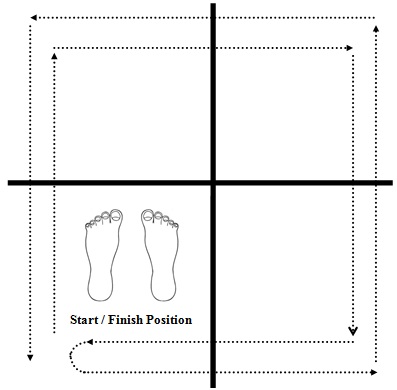

On average, each of the 11 participants played the NWS for ~28 minutes each week across the duration of the study. This mean duration was relatively consistent across the five weeks, with four of the five weeks recording weekly means of 25-33 minutes per participant. The only exception was Week 3 where ~18 minutes per participant were performed (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mean (±SD) weekly Nintendo Wii SportTM play time per participant for each of the five weeks.

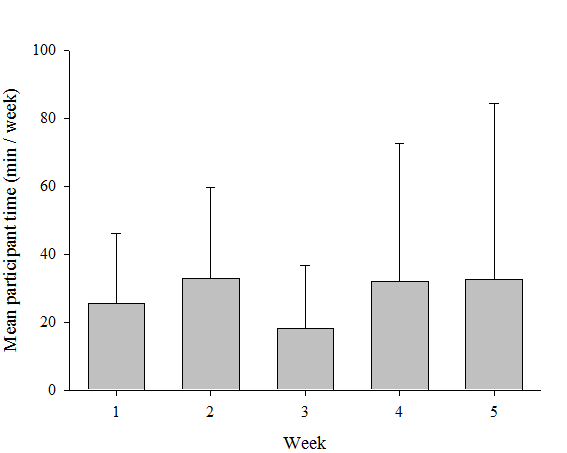

While there was relatively little within-group variability in NWS game time, there was considerable inter-participant variation in the amount and type of NWS game played every week. Five individuals (Participants 7-11) averaged between 44-69 minutes of NWS game time per week, while the remaining six participants (Participants 7-11) averaged 1-21 minutes per week (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Mean (±SD) overall weekly Nintendo Wii SportTM games playing time for all 11 participants.

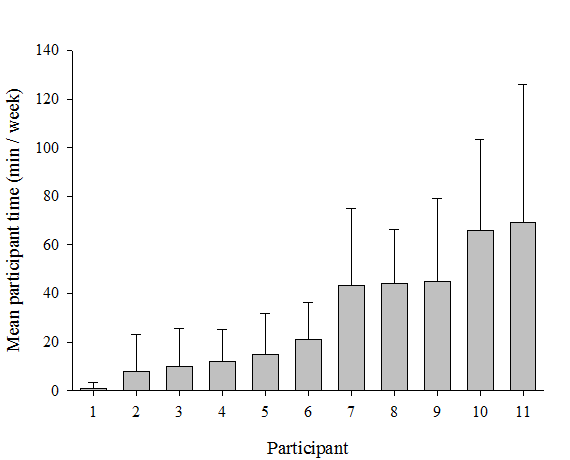

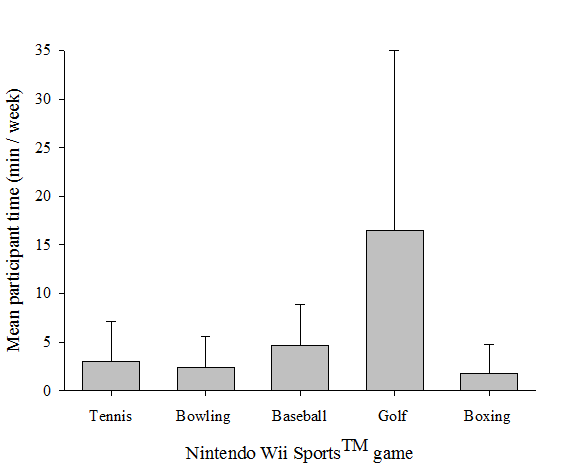

The average participant weekly time spent playing each of the five games is presented in Figure 4. It can be observed that of the five games, golf (~17 minutes per participant week) was played more than the other four games, each of which were played on average 2-5 minutes per participant per week.

Figure 4: Mean (±SD) participant weekly time playing the five different Nintendo Wii SportTM games.

Changes in the FSST, SF-36 and MFES scores are given in Table 1. While no significant changes were observed for any of these variables (p = 0.185-0.841), a moderate effect was observed for the SF-36 Physical component, suggesting an improvement in physical health-related QOL.

Table 1: Changes in outcome measures after five weeks of Nintendo Wii SportsTM games availability (n = 11).

|

Outcome Measure |

Pre-Training |

Post-Training |

Pre-Post Change |

P Value |

Effect Size |

|

FSST(s) * |

21.98 ± 3.24 |

21.55 ± 6.99 |

-2.0% |

0.841 |

-0.085 |

|

SF-36: Physical |

54.5 ± 11.9 |

61.8 ± 13.9 |

+13.3% |

0.185 |

0.563 |

|

SF-36:Mental |

49.5 ± 6.0 |

50.6 ± 7.1 |

+2.2% |

0.608 |

0.176 |

|

MFES |

2.2 ± 1.4 |

2.7 ± 1.9 |

+19.9% |

0.273 |

0.430 |

All results are mean ± SD. Improved function is represented by a decrease in the FSST and an increase in the MFES and SF-36 scores. * Only 8 of the 11 participants were able to complete the FSST.

Participant and Staff themes

Although there was overlapping and interconnection of some commentary, several themes became evident. All the participants spoke of similar experiences which gave rise to the themes of ‘Fear’, ‘Fun’ and ‘Confidence’.

Initially there were tangible feelings of fear expressed by the participants due to their inexperience with ‘technology’ and concern that they may look foolish when unable to use the Nintendo Wii unit. However, it was the themes of ‘Fun’ and ‘Confidence’ that were expressed with more conviction.

Most of the participants’ stated that using the NWS on a regular basis provided a focal point to their day. They enjoyed not only the fact that their ‘activities’ evoked laughter both from other participants and those that were observing, but also the new and strengthening friendships that this facilitated. For some male members of the group the competitions that evolved between each other provided another element of ‘fun’.

Both male and female participants reported the confidence they had gained from having the experience of using the NWS. This confidence was primarily about being capable of using modern technology and feeling pride that they had overcome their initial fear.

At the start of the project, some nursing home staff, while excited about the possibility of the NWS enriching the lives of their residents, had some reservations about the feasibility of the NWS in the nursing home context. However, by the end of the five week intervention they felt that the NWS was an activity that could be relatively easy to incorporate into the nursing home environment, provided there was sufficient space to accommodate the NWS and television, and that there was someone who was able to operate the system and teach the others. Furthermore, the staff stated that most participants appeared relatively confident in operating the NWS at the conclusion of the five week study.

Many notable positive changes in the behavior of the residents were observed by the staff. Prior to commencement of the study several residents were causing concern for staff regarding their reticence to interact and engage in nursing home activities. Nursing home staff indicated that after a short time of interaction with the NWS these residents increased their desire to socialize with their peer group and take part in other nursing home activities. Improved self-confidence, specifically between the study participants was also noticeable. One male participant who had no prior experience or inclination to use any mode of modern technology became confident in the use of the NWS, eventually challenging his grandchildren to participate as well. After several challenging weeks of adjusting to life in the nursing home, another participant found using the NWS a reason to leave his room and interact with other residents. Prior to this he had become depressed and reclusive, spending many hours without interaction with people in the nursing home. Following some encouragement from staff to engage in the NWS he became more positive about his new environment and developed friendships from within the participant group. This enthusiasm was evident when he began greeting the research assistant on her arrival each day.

It is also worthwhile noting that the nursing home management team was significantly impressed with the psychosocial changes in their residents that they purchased a NWS unit after the completion of the study.

Discussion

The present study was conducted to address three separate, but complementary questions relating to the benefits and effects of having the NWS available in nursing homes as previously mentioned.

Limitations affecting the generalisability of these findings included the small sample of 11 participants, no control group, a relatively short intervention phase of five weeks and the use of an informal interview process, with field notes taken rather than direct quotes from a transcribed version of the recorded interview. The use of a self-selected amount and type of NWS playing by the residents instead of a set amount and type of NWS play per week would also be a limitation in determining what amount of interaction with the NWS is required for a given effect. However, by selecting a quasi-experimental design in which each participant was allowed to play any amount and combination of the five NWS games they wished rather than a set amount of play per week, we felt we were able to gain some insight into how this technology might actually be used by nursing home residents in the real-world. Further, we felt that by allowing the residents to play the NWS seated, we demonstrated that nursing home residents who may be unwilling or unable (at least initially) to perform these exercises standing, may still be able to play and gain psychosocial benefits from the NWS.

Nintendo Wii Usage

Inspection of the NWS usage log books revealed some interesting findings. For example, there was a relatively consistent number of mean minutes of NWS played for the entire group of 11 residents across the five weeks of this study. Such a finding suggested that the residents could fit playing the NWS games into their regular weekly schedule and that they did not become bored with this activity over the 5 weeks. Although some studies have involved NWS interventions of 12-22 weeks with community-dwelling older adults (Rosenberg et al., 2010; Vestergaard et al., 2008), the current study is the first to examine patterns of self-selected NWS usage in nursing home residents. Thus, it remains unknown that if given the choice to play the NWS games, would older adults in nursing homes continue this activity in the medium- to long-term and if so, what benefits might be obtained.

Log book data also indicated that there was considerable variation in the amount of NWS played by the 11 participants and the most commonly played NWS game. The inter-participant variation in weekly NWS was quite large, with five participants averaging 44-69 minutes per week and the remaining six participants averaging 1-21 minutes per week. It was also very clear that golf was the most commonly played of the five games. The relative popularity of golf may reflect several factors. The first is a connection to former self (Higgins et al., 2010; Wollersheim et al., 2010), whereby more participants played golf than the other four sports in their younger years. Limitation in the participants’ visual acuity and dexterity could also have been a factor, as games such as tennis and boxing that require faster reactions may prove more difficult for those individuals with reduced visual acuity and dexterity (Wollersheim et al., 2010). Future research should further examine these and other factors so to determine what aspects of the different NWS games most appeal to these older adults. Such data may enable the manufacturers of these games to develop active video games that better meet the wants, needs and abilities of older adults, as well as assist nursing home staff to encourage their residents to play these games on a more consistent basis.

Physical Response

Consistent with the relatively modest amount of self-selected NWS usage by the nursing home residents, no significant quantitative improvements in their dynamic balance or fear of falling were observed. The lack of significant change in the dynamic balance and fear of falling measures were somewhat in contrast to previous NWS studies involving community-dwelling older adults (Vestergaard et al., 2008) and a nursing home resident (Clark & Kraemer, 2009). Our lack of statistical significance may have reflected a variety of differences in our study’s design compared to this literature. Specifically, the studies that reported significant improvements in balance or falling risk measures had therapist supervision, a greater NWS playing duration (6-26 hours) and were played in a standing position rather than seated posture (Clark & Kraemer, 2009; Vestergaard et al., 2008). Therefore, our results are still important as they suggest that if a nursing home purchases a NWS, it will not automatically lead to physical improvements for the residents. Comparison of our results to the literature would suggest that these games need to performed standing and for a minimum weekly frequency, duration and intensity if such results are to occur. What these minimum thresholds are is not currently known. Nevertheless, even self-selected usage of the NWS by nursing home residents could act as a “primer” thus helping to develop their self-confidence. Perhaps some mild-moderate physiological and functional ability improvements are indicated that better enable them to engage in other , efficacious forms of physical activity (von Bonsdorff & Rantanen, 2011).

Psychosocial Response

Although no significant change in the SF-36 QOL scores were observed in the present study, effect size analyses indicated that the 13.3% increase in physical health-related QOL was of a moderate magnitude. Further, this physical health-related QOL response was greater than the 7% significantly greater between-group difference reported in a randomized controlled trial involving the performance of functionally-based activities by nursing home residents (Peri et al., 2008). While no other NWS studies have yet quantitatively examined changes in the QOL of nursing home residents, our results exhibit similar trends to the significant increases in overall (Vestergaard et al., 2008) and mental (Rosenberg et al., 2010) health-related QOL reported for community dwelling elders, and to two qualitative studies (Higgins et al., 2010; Wollersheim et al., 2010) involving predominantly nursing home and community-dwelling older adults, respectively.

The views of the nursing home residents and staff at the conclusion of the intervention were most encouraging as they both expressed some concerns at the start of the project. Specifically, some residents spoke about a fear of technology or of looking foolish in front of their peers when playing the NWS, whereas the staff had some concerns regarding the amount of time and effort they may need to assist the residents in using the NWS. By the conclusion of the study, both the residents and staff felt that the NWS game system could be relatively easily utilized in the nursing home context without too much staff involvement and that its usage led to a number of psychosocial benefits for the residents. Such findings have important implications for both nursing home residents and staff.

The development of competency by the nursing home residents’ in a novel task like the NWS has the potential to increase self-confidence in other aspects of their life (O'Sullivan, 2005). Increases in the residents’ self-confidence and pride in their achievements were some of the themes that emerged from the informal interviews, with their use of the NWS becoming a fun rather than fearful activity. Some of the residents also felt that by playing the NWS they improved their friendships with the other residents and developed an interest to share with their grand-children. The perceptions of the nursing home staff in the present study were also consistent with this view of O’Sullivan (2005), with it felt that a number of residents became more social and self-confident after using the NWS. Somewhat similar findings of improved socialization and/or self-confidence after using the NWS have also been reported by Higgins et al. (2010) for residents and patients in high- and low-dependency care centers (including nursing homes) and by community-dwelling older women (Wollersheim et al., 2010).

The positive reactions of the nursing home staff to not only the psychosocial benefits but also the feasibility of the NWS in the nursing home context was also encouraging. This is important if activities like the NWS are to become a part of usual care practice in nursing homes, as the nursing home staff have a great deal of say in what practices and services the nursing home will provide to, and support for their residents (Chen, 2010; McKenzie et al., 2007). For example, activities that may be considered risky or time-consuming by the staff or that have environmental restrictions regarding space, equipment, costs etc are unlikely to be supported. As the staffs’ views in the current study and that of Higgins et al. (2010) suggest that such concerns regarding using the NWS in nursing homes are relatively modest, the NWS could become a more common aspect of usual care practice in this context in the near future. This may also pave the way for additional ICT to become more commonly available and used in nursing homes.

Conclusions

Overall, the results of this study add to the emerging literature on the possible benefits of physical video games like the NWS for a variety of groups of older adults. Although exploratory in nature, the results of our study suggest that the use of the NWS is feasible in the nursing home context and that the residents may experience some psychosocial benefits after only five weeks of a self-selected amount of NWS game play. This suggests that even short-term unstructured use of this technology may be of some benefit to some nursing home residents. Future research in this area should use randomized controlled trials and examine a larger range of quantitative and qualitative outcomes to gain a greater insight into the benefits, risks, barriers and motives of use for this form of technology with various sub-groups of older adults including those in nursing homes. Such studies would also benefit from following the participants for several months post-intervention to determine if the frequency and duration of NWS changes over time and if this is associated with any alterations in unsupervised and supervised physical activity and other physical and psychosocial outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Health Technology Interface Summer Studentship, AUT University for funding Leslie Wooller to complete this study.

Justin Keogh is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University , Australia, email: jkeogh@bond.edu.au

Nicola Power is the Associate Head, Learning and Teaching in the School of Interprofessional Health Studies, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand, nicola.power@aut.ac.nz

Leslie Wooller is a PhD student in the School of Sport & Recreation, for Auckland University of Technology Auckland, New Zealand, email: leslie.wooller@aut.ac.nz

Patricia Lucas is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Sport & Recreation, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand, email: patricia.lucas@aut.ac.nz

Chris Whatman is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Sport & Recreation, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand, email: chris.whatman@aut.ac.nz

References

Brown, V. M., Allen, A. C., Dwozan, M., Mercer, I., & Warren, K. (2004). Indoor gardening and older adults: effects on socialization, activities of daily living, and loneliness. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 30(10), 34-42.

Burmeister, O. K. (2009). What users of virtual social networks value about social interaction: The case of GreyPath. In N. Panteli (Ed.), Virtual Social Networks: Mediated, Massive and Multiplayer (pp. 114-133). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Burmeister, O. K. (2010). Virtuality improves the well being of seniors through increasing social interaction. In J. Berleur, M. D. Hercheui, L. M. Hilty & W. Caelli (Eds.), What Kind of Information Society? Governance, Virtuality, Surveillance, Sustainability, Resilience (pp. 131–141). Berlin: Springer.

Chen, Y.-M. (2010). Perceived barriers to physical activity among older adults residing in long-term care institutions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(3-4), 432-439.

Clark, R., & Kraemer, T. (2009). Clinical use of Nintendo Wii bowling simulation to decrease fall risk in an elderly resident of a nursing home: a case report. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 32(4), 174-180.

Dite, W., & Temple, V. A. (2002). A clinical test of stepping and change of direction to identify multiple falling older adults. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 83(11), 1566-1571.

Drexler, K. (2009). Case history: Use of the NintendoWii to increase fine motor dexterity post cerebral vascular accident. American Journal of Recreation Therapy, 8(3), 41-46.

Epstein, L. H., Beecher, M. D., Graf, J. L., & Roemmich, J. N. (2007). Choice of interactive dance and bicycle games in overweight and nonoverweight youth. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(2), 124-131.

Fiatarone, M. A., O'Neill, E. F., Ryan, N. D., Clements, K. M., Solares, G. R., Nelson, M. E., et al. (1994). Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. New England Journal of Medicine, 330(25), 1769-1775.

Frontera, W. R., Hughes, V. A., Fielding, R. A., Fiatarone, M. A., Evans, W. J., & Roubenoff, R. (2000). Aging of skeletal muscle: a 12-yr longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Physiology, 88, 1321-1326.

Graves, L., Stratton, G., Ridgers, N. D., & Cable, N. T. (2007). Comparison of energy expenditure in adolescents when playing new generation and sedentary computer games: cross sectional study. British Medical Journal, 335(7633), 1282-1284.

Hedström, K. (2007). The values of IT in elderly care. Information Technology & People, 20(1), 72-84.

Higgins, H. C., Horton, J. K., Hodgkinson, B. C., & Muggleton, S. M. (2010). Lessons learned: Staff perceptions of the Nintendo Wii as a health promotion tool within an aged-care and disability service. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 21(3), 189-195.

Hill, K. D., Schwarz, J. A., Kalogeropoulos, A. J., & Gibson, S. J. (1996). Fear of falling revisited. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 77(10), 1025-1029.

Hill, N. L., Kolanowski, A., & Kurum, E. (2010). Agreeableness and activity engagement in nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 36(9), 45-52.

MacRae, P. G., Asplund, L. A., Schnelle, J. F., Ouslander, J. G., Abrahamse, A., & Morris, C. (1996). A walking program for nursing home residents: effects on walk endurance, physical activity, mobility, and quality of life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 44(2), 175-180.

Maddison, R., Mhurchu, C. N., Jull, A., Jiang, Y., Prapavessis, H., & Rodgers, A. (2007). Energy expended playing video console games: an opportunity to increase children's physical activity? Pediatric Exercise Science, 19(3), 334-343.

Masel, M., Graham, J., Reistetter, T., Markides, K., & Ottenbacher, K. (2009). Frailty and health related quality of life in older Mexican Americans. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(1), 70.

McHorney, C., Ware, J. E., Jr. , & Raczek, A. (1993). The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care, 31, 247-263.

McKenzie, R., Naccarella, L., & Thompson, C. (2007). Well for Life: Evaluation and policy implications of a health promotion initiative for frail older people in aged care settings. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 26(3), 135-140.

Nelson, M. E., Rejeski, W. J., Blair, S. N., Duncan, P. W., Judge, J. O., King, A. C., et al. (2007). Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 39(8), 1435-1445.

Newman, L. A., Biedrzycki, K., & Baum, F. (2010). Digital technology access and use among socially and economically disadvantaged groups in South Australia. Journal of Community Informatics, 6(2). Retrieved from http://ci-journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/639/582doi:http://ci-journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/639/582

O'Sullivan, G. (2005). Protocols for leisure activity programming. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 52(1), 17-25.

Pasch, M., Berthouze, N., Dijk, B. v., & Nijholt, A. (2008). Motivations, strategies, and movement patterns of video gamers playing Nintendo Wii boxing. In A. Nijholt & R. W. Poppe. (Eds.), Facial and bodily expressions for control and adaptation of games (ECAG 2008) (pp. 27-33). Enschede, The Netherlands: Centre for Telematics and Information Technology, University of Twente.

Peri, K., Kerse, N., Robinson, E., Parsons, M., Parsons, J., & Latham, N. (2008). Does functionally based activity make a difference to health status and mobility? A randomised controlled trial in residential care facilities (The Promoting Independent Living Study; PILS). Age and Ageing, 37(1), 57-63.

Rosenberg, D., Depp, C. A., Vahia, I. V., Reichstadt, J., Palmer, B. W., Kerr, J., et al. (2010). Exergames for subsyndromal depression in older adults: a pilot study of a novel intervention. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(3), 221-226.

Shalala, D. E., Satcher, D., Koplan, J. P., & Sondik, E. J. (1999). Health, United States. 2002, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus99cht.pdf

Shankar, K. (2010). Pervasive computing and an aging populace: Methodological challenges for understanding privacy implications. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 8(3), 236-248.

Tinetti, M. E., Richman, D., & Powell, L. (1990). Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. Journal of Gerontology, 45(6), P239-243.

Unnithan, V. B., Houser, W., & Fernhall, B. (2006). Evaluation of the energy cost of playing a dance simulation video game in overweight and non-overweight children and adolescents. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 27(10), 804-809.

Van Leuven, K. A. (2009). Health practices of older adults in good health. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 36(6), 38-46.

Vestergaard, S., Kronborg, C., & Puggaard, L. (2008). Home-based video exercise intervention for community-dwelling frail older women: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 20(5), 479-486.

von Bonsdorff, M., & Rantanen, T. (2011). Progression of functional limitations in relation to physical activity: a life course approach. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 8(1), 23-30

Whitney, S. L., Marchetti, G. F., Morris, L. O., & Sparto, P. J. (2007). The reliability and validity of the Four Square Step Test for people with balance deficits secondary to a vestibular disorder. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(1), 99-104.

Wollersheim, D., Merkes, M., Shields, N., Liamputtong, P., Wallis, L., Reynolds, F., et al. (2010). Physical and psychosocial effects of Wii Video game use among older women. International Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society, 8(2), 85-98.