Integration of ICT Into Curricula in Western Cape Schools: The Activity Theory Perspective

- Associate Professor, IT Department, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa. Email: mlitwan@cput.ac.za

- Masters Student, IT Department, FID, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa.

INTRODUCTION

Information and communication technology (ICT) and its continuous innovations have improved efficiencies in various domains of modern living. Efficiencies through e-Government (Dwivedi & Bharti, 2005; Gupta, 2011), e-Commerce (Goel, 2007), e-Health and e-Learning solutions are such examples. Access to quality education in particular, is enhanced through web-enabled educational software, systems and networked applications (Jhurree, 2005; Bunt-Kokhuis, 2012). Educational software aids in simplifying difficult concepts, making learning fun and easy (Simkins et al., 2003). Most significantly, Mobile (M) and Electronic (e) Learning in particular, allow learning to be done anywhere and at anytime (Goi & Ng, 2009).

With access to ICT, all learners in South African (SA) schools can benefit from these efficiencies. However, access to educational technology in SA is still limited to the advantaged few in the more urban areas whilst many learners in disadvantaged areas remain on the periphery during the time of writing this work (Mlitwa & Nonyane, 2008; Nonyane, 2011). For this reason, the government has undertaken, through the e-Education policy of 2004, to equip schools with ICT. The goal was to empower schools with ICT facilities to improve the quality of education so as to improve learning outcomes (Eom, et al., 2006) in all schools. This policy provides for the deployment of educational hardware and software to every school in SA, and for a full integration of ICT into curricula, including the e-skilling of teachers (by integrating ICT skills programs into the teacher-training curriculum).

Research Problem

The main problem was that whilst policy provisions are inspiring, schools in rural areas remain under-resourced, lacking basic infrastructure including ICT resources. Even in urban areas with notable initiatives such as the 'Khanya Project' and 'Gauteng Online', universal success remains elusive, as many schools are yet to be catered for (The Khanya Project, 2010; Gauteng Online, 2010). It is also unclear why a number of schools remain under-resourced, with the majority of teachers still computer illiterate. Unless the situation is clearly articulated and understood, learners in affected schools may continue to be marginalized, with bleak chances of being competitive in their future careers and ultimately, of improving the quality of their lives.

Research Objective

The aim of our research was to understand the challenges in the integration of ICT into schools and schools' curricula in disadvantaged areas of the Western Cape, so as to inform possible solutions.

A research question "how can the discrepancies in the deployment and integration of ICT into curricula in disadvantaged schools in low income communities in the Western Cape be addressed" was raised as a basis for the investigation. The following sub-questions were also identified:

- How is ICT being deployed into disadvantaged schools?

- How is ICT being integrated into school curricula in these areas?, and

- Why are teachers not integrating ICT into curricula in disadvantaged areas?

METHODOLOGY

The work of the paper is predominantly qualitative, in that data is descriptive and explanatory rather than statistical. Given the appropriateness of a case studies for in-depth insight into social phenomena (Yin, 1994), a case study method was used. In this respect, the interpretivist paradigm was followed, using both secondary (literature) and primary (semi-structured interviews) data sources. Content analysis in conjunction with a theoretical framework - the e-Schools Activity Theory Framework, was used to analyse and interpret data.

Since the aim of the study was to identify specific cases with conditions typical to the problem under investigation, a purposive method of sampling was used to select participant samples in 4 schools (i.e. Kulani Secondary, Sithembele Matiso Secondary, Macassar Secondary and Marvin Park Primary in the Western Cape (WC)).

Purposive sampling is a technique used to select a sample from a research population, purely according to the intentions (judgment) of the researcher as guided by the purpose of the study (Babbie, 2010). This technique is most appropriate when a researcher has "clear characteristics of the participants needed" (Mlitwa, 2011), and where a sample can be selected upon which conclusions about the targeted population can be drawn (Babbie & Mouton, 2001). In this instance, the researcher can approach only the members of the population that are ready and willing to offer data (Kumar, 2005).

The WC province was selected in acknowledgement of progressive efforts of the Khanya project where all schools are expected to be equipped with ICT resources. The province was also selected on the basis of its close proximity to the researchers. The Provincial Department of Education (DoE) list of schools was used to identify and select school for our sample. One school was selected from an informal settlement and one from a formal township among traditionally black (African) residential settlements. Another school was selected from a low income Suburb and from the traditionally Coloured informal settlement area of the WC. The idea of this mix was to draw insight from the variety of underprivileged contexts in the region.

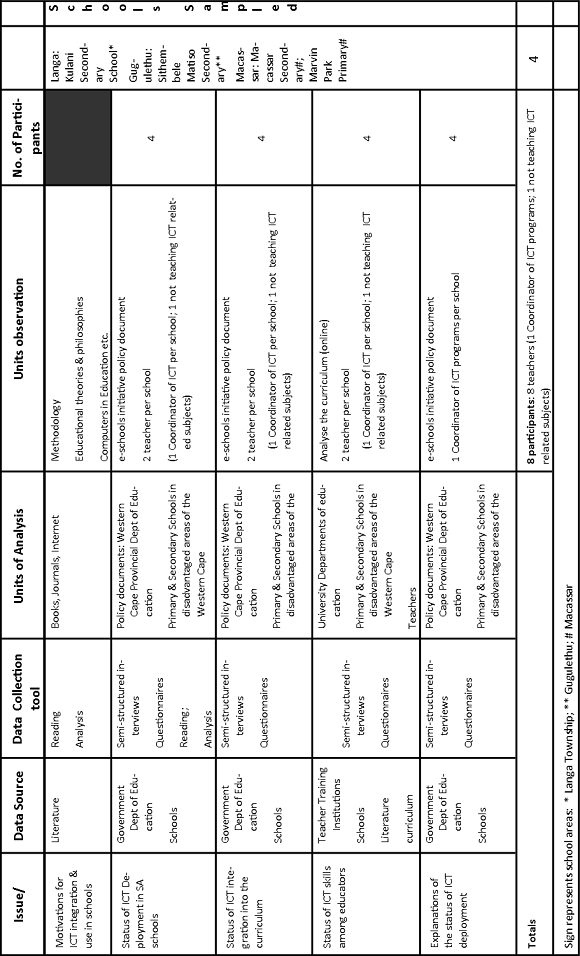

As outlined in Table 1 below, coordinators of ICT programs in the WC DoE, and in schools (e-schools coordinators) as well as educators were the population from which research samples were selected.

Guided by the literature background, our research question/s and research objective have been translated into five issues for investigation, (1) Motivations for ICT integration and use in schools; (2) Status of ICT Deployment in SA schools; (3) Status of ICT integration into the curriculum; (4) Status of ICT skills among educators, and; (5) Explanations as to the status of ICT deployment (see Table 1).

ICT as a Tool and a Catalyst for Development

ICT is said to improve educational efficiencies, and is a significant means to address educational shortcomings in the developing world (Mlitwa, 2011; Gutterman, et al., 2009). Against this background, world governance structures committed through the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to exploit ICT in redressing social inequality among world populations, by halving the poverty, disease and illiteracy rates by 2015 (MDG report, 2008). Achieving universal access to primary education is presented as the second highest priority (after poverty reduction) in the MDGs, with ICT as the major enabler (Nonyane, 2011). Similar undertakings have also been instituted by multinational institutions and in continental structures. At multi-national level, the Global e-Schools Communities Initiative (GeSCI) i emphasizes the deployment of ICT in schools, to improve teaching and learning in developing countries (GeSCI, 2009).

Continental structures in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, have also turned to ICT for solutions in advancing the quality of, and access to education (IDB, 2000). The Policy Forum ii on the Integration of ICT into Education by ten Asian countries in 2007 (World Links, 2007) is an example. In the same light, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) also established the UNESCO SchoolNet project in 2003. The goal was to improve teaching and learning outcomes through teacher training as well as the integration of computers into school programs (ASEAN, 2010). In Africa, the New Partnership for African Development (NEPAD) also established the e-Schools initiative with the objective of providing computers to every school on the African continent (The Nepad e-Africa Commission, 2010). Through this initiative, NEPAD also undertook to advance ICT skills to primary and secondary school students as well as educators. Through this initiative, NEPAD also undertook to coordinate ICT curriculum and content development in all schools in Africa, so as to enhance the quality of schooling across the continent (ibid).

Within individual countries, South Africa also established the e-Education policy in 2003 (DoE, 2003). In this policy, ICT is viewed as a resource for teaching and learning, and an enabler of the development of the school as a whole. On this basis, the e-Education policy aims to equip schools with ICT to improve management and administration; to facilitate the incorporation of ICT into the curricula; and to improve communication and engagement as well as collaboration between teachers and between learners (DoE, 2007). The goal is to ensure that every learner is able to use ICT confidently and creatively and to develop the skills and knowledge needed to achieve personal goals. In this quest, further provisions are to integrate ICT into all South African schools by the year 2013 (DoE, 2003).

The idea is to push for universal access to ICT, through the deployment of networked computers, educational software and online learning resources to all schools in South Africa. The intention is to enable the development and distribution of electronic learning content so that every learner, teacher, manager and administrator has the knowledge, skills and support needed to integrate ICT into educational processes. Guidelines to integrate ICT into the teacher pre-service and in-service training programmes are also outlined in the policy. To facilitate implementation, the policy provides for the assigning of a "dedicated teacher to manage ICT facilities and to champion the use of ICT", and the provision of technical training for teachers in every school (DoE, 2003).

ICT facilities and ICT skills are important, but need to be productively integrated into the curriculum if they are to make a positive impact in education (Mlitwa, 2010). A Curriculum entails the philosophy, the content, the approach and the assessment of a learning programme (Harvey, 2004). Integrating ICT into the curriculum therefore, implies the alignment of educational technologies with pedagogy.

Given that the e-Education policy was put forward in 2003, it is logical to expect that reasonable progress in the integration and deployment of ICT into the school curriculum, should have taken place by the year 2012.

This study investigates the dynamics of the e-Education policy implementation, with emphasis on its goal to deploy and integrate ICT into curricula, in all South African schools. Selected schools in underdeveloped areas of the Western Cape were chosen as case samples. Activity theory (AT) was used to provide an analytical framework for the study.

A Theoretical Framework: Activity Theory (AT)

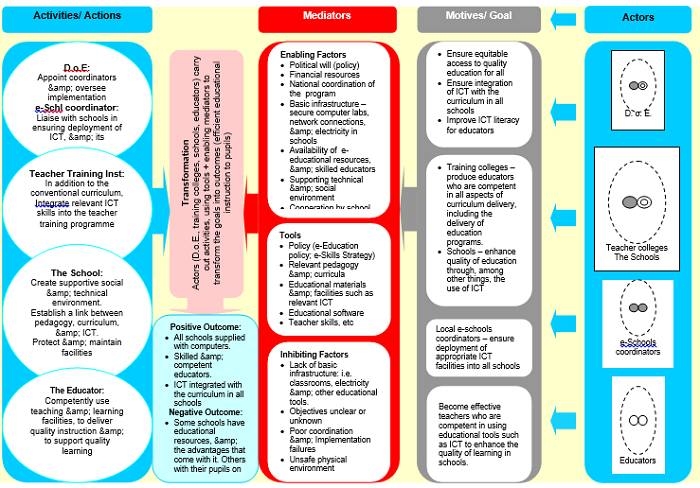

AT is used as a framework for examining and transforming networks of interacting activity systems (Hardman, 2005). The activity systems transform one condition to another, hence are considered to be the instruments of re-organisation (Engeström, 1987). The basic components of an activity system are comprised of the subject, object, mediating artifacts (i.e. tools), rules, community and division of labour (ibid). The subject is an individual or entity (actor or actors) from whose perspective an object is to be viewed (Daniels, 2004). In the case of this study, actors are the Government (DoE), teacher training institutions and schools at the institutional level, as well as Provincial e-Schools co-ordinators, schools ICT coordinators and individual educators. An object is the reason for an action or the goal (Engeström, 1987). As detailed in Figure 1, the goals of the DoE, and the provincial and school level implementers vary in terms of roles, though overlapping in the main goal of achieving full integration of ICT into curricula, and in improving the quality of learning outcomes.

Mediation refers to the use of tools to mediate human activity (Vygotsky, 1978). The tool is the artifact to be created and transformed during the development of the activity itself (Uden & Damiani, 2007). Rules are the norms and regulations that are either implicit or explicit, but influential in the activities that take place (Engeström, 1999). The community represents groups, rules and arrangements such as the division of labour (Owen, 2008). The problem with goal implementations in a multi-level and complex activity system such as the e-Schools process is that it needs clear rules and guidelines across different actors if it is succeed. Whilst implicit guidelines may be ambiguous, subject to misinterpretation and manipulation, the worst situation would be a complete lack of rules or guidelines and enforcement procedures.

Rather than a predictive theory, AT is a descriptive framework, a concept and a theoretical approach or a viewpoint (Mursu et al., 2007). In most instances AT is used to analyse human activity from a needs-based and goal-oriented viewpoint (i.e. people are driven by needs and therefore have specific goals to achieve) (Mlitwa, 2011). Consequently it is used to understand human interaction through mediated tools and artifacts (Hashim & Jones, 2007). An activity is seen as a factor that ties the actions to the context, hence an activity is a basic unit of analysis in Activity Theory (Engeström, 1987). Since human actions derive their meaning from the context, "actions without context are meaningless" (Mursu, et al., 2007:6). Thus actions must be viewed within a context (Leont'ev, 1978). As outlined in Figure 1, different functions (activities of different actors) in the policy implementation process investigated in this study are such units of analysis.

The Use of Activity Theory in this Research

As indicated in Figure 1, the AT work-activity concepts are used to present the e-Schools programme as an activity system. An actor is an individual, a group of people (Engeström, 1987) or even an entity/institution (Mursu, et al, 2007). The motives/goals refer to the DoE policy undertaking to deploy and integrate ICT into curricula in all school. This goal is associated with relevant activities such as budget provision, communication with relevant stakeholders, monitoring and enforcing the implementation. At a teacher training institution, the goal is simply to see the teacher training programme integrated to include ICT, and to produce ICT literate (and competent) teachers. At a school level, coordinators want to see full deployment, maintenance and use of ICT for educational purposes in their respective centres of operation. Under this framework, the goal of teachers is to competently use ICT to improve learning outcomes.

Mediators are factors that can enable or inhibit the successful achievement of a goal (Vygotsky, 1978). For example, it is unhelpful to have clear goals, actors and rules, but lack financial resources; coordination of activities and of the integration process; basic infrastructure such as classroom and electricity; or to not have ICT literate teachers. The transformation process combines the enabling factors, the tools and the activities, in order to achieve a positive outcome (Uden & Damiani, 2007).

The relevance of AT in this study is that it provides a holistic operational view of phenomena at hand. From an AT perspective the e-School Activity Theory Analytical Framework (Figure 1) aids in understanding the factors affecting the successful realization of the government's e-Education policy goal (i.e. universal access to ICT for teaching and learning).

Information flows and linkages between the components of the activity system are important in the success of the work-activity.

Without duplicating the content of Figure 1 and the preceding discussion, the framework was useful in clarifying the context of the investigation, to frame the concepts, work-flows between actors, and to clarify mediators (including tools) as well as activities in this project. In conjunction with the content analysis tool, the framework also informed the identification of themes towards the analysis and most significantly, the interpretation of data. To this end, findings expose the current status of ICT integration into schools and schools' curricula.

FINDINGS

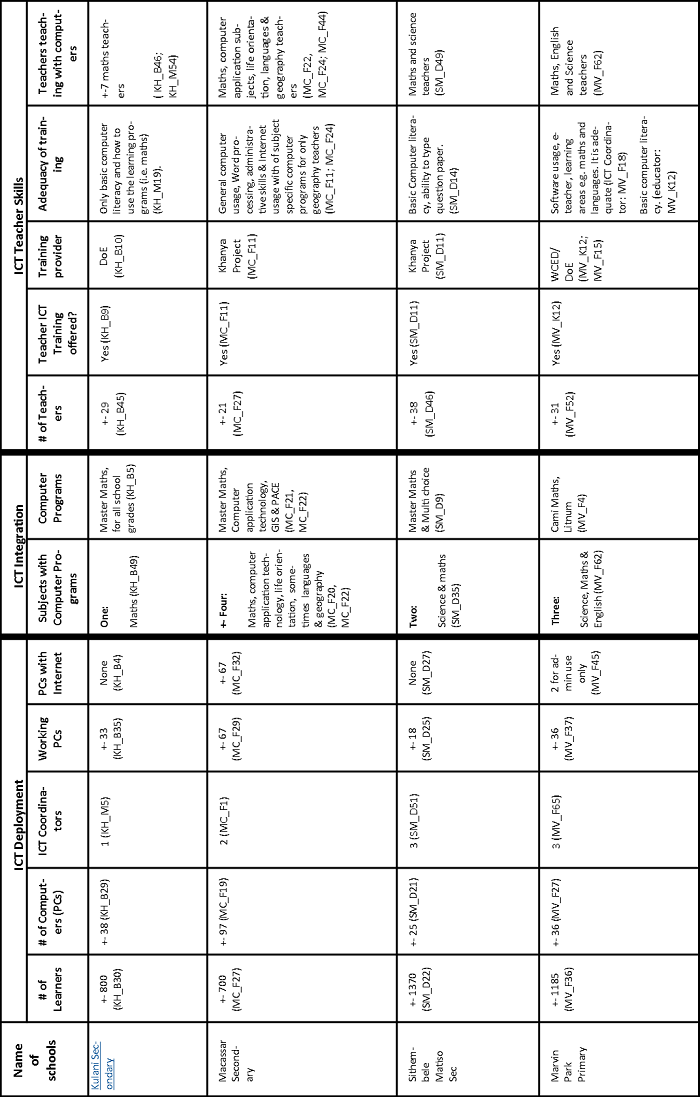

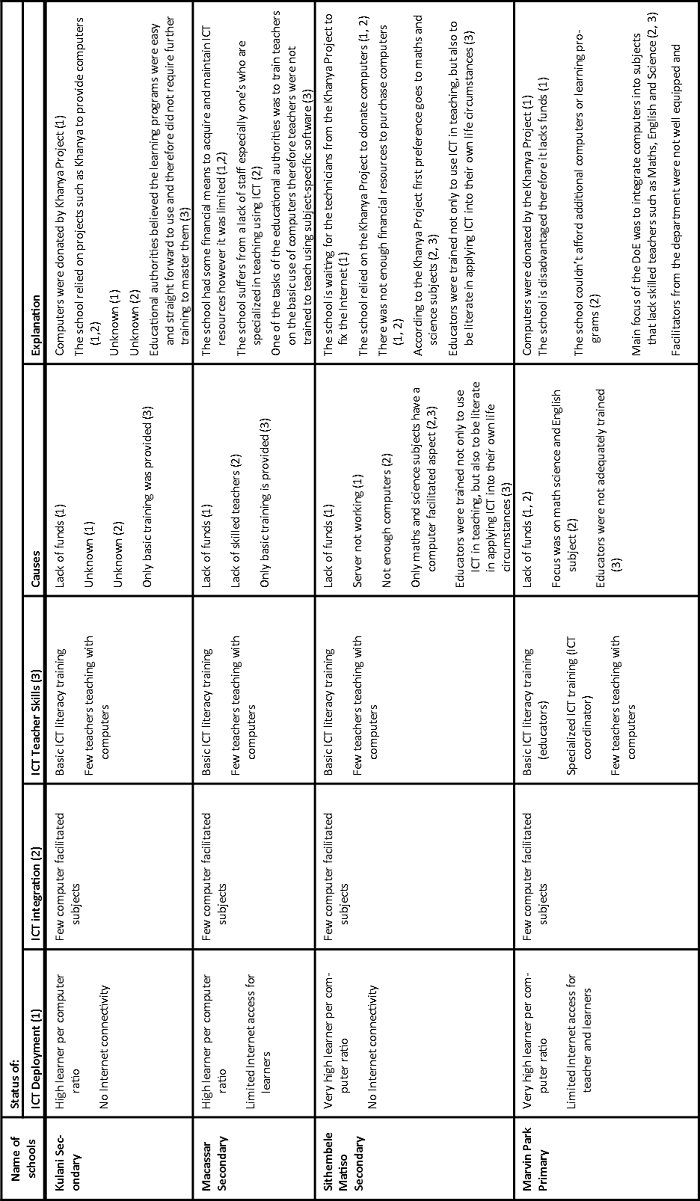

Findings are presented in Tables 2 & 3 and discussed in sections that follow.

DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS

Deployment of Computers into Schools

The goal of the main actor (the national DoE) according to the theoretical framework in Figure 1 was to ensure that all schools are equipped with physical infrastructure in the form of computers, internet and computer-based educational programmes. Secondly, the assumption in the theoretical framework is that success in this endeavour is dependant on a positive interaction between this intention (goal), the responsibilities of each actor in the framework, the enabling environment in terms of the presence of all enabling mediators, and the correct implementation of all activities by respective parties. However, findings (Table 2) reveal a disappointing learner-to-computer ratio. That is, out of the 4 schools, Macassar Secondary has the lowest ratio of 10 learners per computer (MC_F29), followed by Kulani Secondary with a ratio of 24 learners per computer (KH_B35). Although Macassar had the lowest learner computer ratio in comparison to the other 2 schools in the sample, the ratio is still not practically ideal.

Whilst a ratio of 1 learner per computer is preferable, such an expectation would understandably be utopian in a context of a developing country. On this basis, a compromise standard of 5 learners to 1 computer has been adopted in developed countries (USA DoE, 2000). Despite the policy support however, the situation is disappointingly sub-marginal in sampled schools. Whilst the learner per computer ratio is 10 learners per computer at Macassar (MC_F29), and 24 learners per computer at Kulani secondary schools (KH_B35), the situation is worse at Marvin Park Primary and Sithembele Matiso Secondary. Marvin Park has a ratio of 33 learners to 1 computer (MV_F37), and 76 learners per computer at Sithembele Matiso (SM_D25). The reality of these 33 learners sharing one computer can lead to non-completion of individual learning tasks, and ultimately, stagnation in academic progress.

On the other hand, although the ratio of 33 and 76 may be numerically lower than the ratio of 312 learners per computer in many underdeveloped countries, a better situation would have been expected in 2011, given that the policy had been in place since 2003. Given the pressure of assignment deadlines for learners, the practicality of 33 learners sharing 1 computer is questionable. At 76 learners per computer, it is even harder to imagine the integration and application of ICT into curricula that require learners to complete tasks individually.

Although both Macassar Secondary and Marvin Park Primary had Internet connectivity, access to the Internet was limited (MC_F32). For example, only Macassar had a full Internet connection. In this instance, both teachers and learners were using the Internet. It is regrettable as well, that learners were only allowed to do so after school hours (MC_F33). Even then, learners need to apply for permission before they could be granted access (ibid). During the period of access, a learner is granted only a few minutes, which is hardly adequate to complete an assigned task (MC_F33). Though the school seemed to have full Internet access, time restrictions meant that access was not full and thus limited for learners.

As if the limitation of Internet was not inhibiting enough to educational processes, two additional schools - Sithembele Matiso Secondary (SM_D27) and Kulani Secondary (KH_B38) - did not have any form of Internet connectivity, whatsoever. As a result, some of the teachers had to travel to nearby schools to access the Internet (SM_D27). If the main goal of ICT integration is to improve teaching, learning, and ultimately, learning outcomes, limited access reduces such benefits to learners. In this unfortunate situation, both teachers and learners are deprived of the benefits associated with the use of the Internet (i.e. fast information distribution, anytime anywhere access, communication, administrative assistance, accommodation of various levels of learning, increased learners understanding, distribution of learning materials and so on).

In terms of the analytical framework in Figure 1, deployment and integration of ICT into schools' curricula are the goals that depend on key mediators to succeed: enabling policy, finance, availability of basic infrastructure such as electricity and classrooms, competent coordinators, skilled educators and effective communication between all stakeholders. Discrepancies in mediating factors, including unclear communication channels between all stakeholders, are correlated to the negative status quo.

Integration of Computers into School Curricula

Findings indicate that very few courses/subjects were facilitated with computers in the sampled schools. Only 3 out of 9 subjects in Marvin Park (MV_F59; MV_F62) and 3 out of 12 subjects in Macassar Secondary (MC_F20; MC_F21) had a computer-facilitated aspect. Sithembele Matiso only had 2 out of the 12 subjects (SM_D35; SM_D40) whilst Kulani Secondary had only 1 out of 13 subjects (KH_B5; KH_B51) that had any computer-facilitated elements. Mediating factors towards this end according to Figure 1 would be the presence of infrastructure, computer-based educational programmes, clear curricula and skilled teachers, supported by activities where trainers provide adequate training to the teachers, suppliers provide resources and coordinators do their part. Findings reveal a clear discrepancy in these respects, which suggest significant gaps in the e-Education policy implementation process.

ICT Skills Amongst Educators

As has been mentioned, very few subjects in these four schools were taught using subject specific learning programs (MC_F22; MC_F24; MC_F44). In Macassar Secondary, 3 subjects out of 12, maths, computer application and life orientation (MC_F20; MC_F21). In Marvin Park, 3 subject out of 9 English, maths and science (MV_F59; MV_F62). In Sithembele Matiso, 2 subjects out of 12, maths and science (SM_D35; SM_D40), and in Kulani Secondary, one out of 13 subjects maths (KH_B5; KH_B51). In addition to a lack of educational software for the rest of the subjects, a lack of relevant skill and access to training opportunities among the majority of teachers is also a strong limiting factor. With regards to training, most educators in sampled schools had only received basic computer literacy training (KH_B13; MC_F11; SM_D14; MV_F18), which did not help improve competency in using educational software.

Findings reveal a bleak picture in terms of the student to computer ratio, and the progress in terms of ICT integration into curricula in schools. Limited ICT literacy among educators in sampled schools emphasizes this point. These three aspects are the key objectives of the policy. Given the period in which the policy has been in existence (since 2003), the status suggests clear failure in the policy implementation process. The framework (Figure 1) suggests that successful deployment and integration of ICT into schools, and a high computer literacy among teachers would depend on a number of mediating factors: an enabling policy environment, the appointment of competent coordinators, clarity in the ICT component in teacher training institutions, clear channels of communication between all stakeholders in the activity system, basic infrastructure at school and a continued provision of relevant education software in schools. Whilst the policy, the will and some promising initiatives are is in place, there seem to be contradictions in terms of implementation priorities among national, provincial and school-level stakeholders. For example, most coordinators were aware of what they should be doing when there are no facilities, or when facilities are inadequate or malfunctioning. The case of schools with facilities (computer and internet) but restrictions on learners using them demonstrates this point.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Considering the findings, we conclude that the goal of the e-Education policy to ensure universal access to ICT, full integration of ICT into school curricula, and that teachers are competent and able to teach using ICT has hardly been achieved. If the inhibiting factors are not addressed, learners in affected schools will continue to lack ICT access and the associated opportunities towards quality education. This can hinder their progress in life and their future contributions to the country's economy.

With a policy having been in place for over a decade, it would be expected that supporting factors such as financial resources would be available for this purpose. However, financial issues continue to be cited as the main hindrances in schools. Within school budgets, ICT related facilities also appear to have a very low priority. Given clear policy pronouncements however, this can be more attributed to poor coordination of human and financial resources than to a lack of political will.

At the time when the quality of school education is in dire need for improvement, it is clear (unfortunately so) that the current model of deploying ICT resources into schools is not working. A recommendation therefore, is that authorities should review the efforts made to deploy ICT into schools and possibly appoint personnel to audit the process, including the funding model.

However, the problem in the sampled schools is larger than just financial limitations. There is also a clear lack of common understanding between school communities and policy makers, with teachers and ICT coordinators not knowing the ICT deployment details for their schools. The Work Activity Framework in Figure 1 presents this aspect as key mediating factors whose presence or absence would determine whether the outcomes sought are achieved or not. On this point, we recommend a revised communication process between the national, provincial and local (school) coordinators on the full details of ICT deployment in schools. In other words, school principals and coordinators must be aware, and be clear about the number of computers, maintenance needs and procedures as well as specific software and connectivity details required in their schools.

The supporting technical and social environments (Figure 1) are also necessary. A supporting social environment is a secure environment where facilities are not vandalized, and there is a willingness of teachers and learners to make use of ICT in education. The actual delivery of tools: computers, Internet, educational software, printers, scanners and copiers etc) and its integration into educational programmes are also emphasized in the framework.

The causal factors for the poor status of ICT integration according to the educators were a lack of educational software and relevant ICT (KH_B49; MC_F29; SM_D53; MV_F21). Furthermore the organisations involved in deploying ICT into schools mainly focused on specific subjects and not into the full curricula (The Khanya Project, 2010). In this regard there seems to be a misunderstanding of priority needs in support of e-Schools programs Teachers tend to limit ICT relevance only to maths and science subjects (KH_B5; SM_D9; MV_62), with a complete neglect of other subjects.

With the e-Education policy advocating for a full integration of ICT into school curricula it would be expected that funds have been allocated to achieve this goal. However, funds allocated for the acquisition of ICT resources (i.e. education software) are cited as inadequate, lacking, or completely unheard-of, which suggests unclear guidelines in this activity system. Nonetheless the problem seems to be bigger than poor coordination of financial resources.

There also appears to be a lack of clear guidelines for implementation. We recommend that stakeholders in the e-Schools activity system (authorities and e-Schools coordinators) liaise with schools to ignite the implementation process. Educational authorities should also invest in teacher training programs and ensure that competent facilitators are appointed to train educators. Also the training programs provided should be constantly revised. Further, whilst tools are important, the work activity framework presents a need for technically skilled teachers as a basis for a successful integration of computer technology into curricula. In other words it is only when teachers are skilled that they will be able to use educational technology to facilitate teaching, thus emphasis should be placed on helping teachers to master subject specific learning programs, before expecting them to use these in their classes.

Considerations for Further Research

A theoretical framework in Figure 1 offers a practical approach to viewing a complex socio-technical phenomenon such as the deployment of ICT, and its integration into schools' curricula. Practically, the work offers analytical tools that can assist planners, policy makers and other interested parties make sense of the underlying factors surrounding the implementation of technology policies in the societal settings.

A replication of a similar study in other provinces, as well as a comparison of ICT deployment efforts between technologically developed and disadvantaged schools in future studies, is also recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the people and institutions that contributed to the successful completion of this study: the Western Cape Department of Education (WCED), the sampled schools, the interview participants, your time and contribution is appreciated.

ENDNOTES

i The Global e-Schools and Community Initiative

(GeSCI) is based on the consensus belief within the

United Nations, that education in developing countries

needs critical attention. Funded by Ireland, Sweden,

Switzerland and Finland, GeSCI has undertaken to invest

in, and deploy ICT to improve teaching and learning in

developing countries (GeSC, 2009).

ii This forum develops policies to ensure a successful integration of ICT in the classroom. The I-Schools Project (to develop open content to enable the equal access to education for learners), and the Smart Schools Program (that promotes access and use of ICT for teachers) are some of the collaborative initiatives of the forum (World Links, 2007).