Participatory Development of ICT Entrepreneurship in an Informal Settlement in South Africa

- Head of School: School of Information Technology, Monash University, South Africa. E-mail: jacques.steyn@monash.edu

- Senior Researcher: CSIR Meraka Institute, Pretoria, South Africa. E-mail: mrampa@csir.co.za

- Principal Researcher: CSIR Meraka Institute, Pretoria, South Africa. E-Mail: mmarais@csir.co.za

1. INTRODUCTION

The research question addressed in this project was whether it would be possible to equip some individuals in a poor and disadvantaged community with entrepreneurial skills to start Information and Communication Technology (ICT) related businesses. In order to avoid the shortcomings of top-down approaches to development projects, a participatory action research methodology was followed. Individuals with rudimentary ICT knowledge were chosen to participate. The project was implemented in an informal settlement (Zandspruit) north-west of Johannesburg, South Africa and was called Participatory Entrepreneurship Development (PED). The project included a diverse mix of stakeholders: the School of Information Technology (IT) of Monash University (South African campus), Ungana-Afrika (a NGO focusing on using technology to develop under-served communities), the Meraka Institute of the CSIR (a technological R&D institute reporting to the South African parliament), Medupe (one of Zandspruit's Community-Based Organisations, orCBO's), which offers advanced ICT training courses combined with business skills training), and Zandspruit community members. Medupe was the main source of participants that wanted to become local ICT entrepreneurs.

The selection of tools used within the participatory action research framework was: Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) (Cavestro, 2003), Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA), IDEO's Human Centered Design Toolkit (IDEO, 2008), and Ethnographic Action Research (EAR) (Tacchi et. al., 2007). Based on the assumption that knowledge of how a new business is established and operates is a fundamental requirement, participants received training in basic business concepts. Through conversation and brainstorming, participants (as representatives of the Zandspruit community) had to identify community needs, and how new businesses could address those needs. It was hoped that with their knowledge of ICT, ideas would be generated for the establishment of new businesses (run by local entrepreneurs) that could harness the potential of ICT.

2. BACKGROUND

Entrepreneurship

There is no consensus on the meaning of "entrepreneurship" and there is no settled single theory of entrepreneurship (Anderson and Starnawska, 2008; Swedberg 2007). Robinson (2002) indicates a range of meanings, from what might be called high-level entrepreneurs to low-level entrepreneurs - although he does not use these terms. Definitions of high-level entrepreneurs build on Joseph Schumpeter's framework with "revolutionary innovation" as the fundamental notion. Schumpeter assumes productivity and efficiency as the major drivers, characterized by the introduction of innovative products, services, processes, or organizational systems. Such entrepreneurs are highly creative individuals, and they typically constitute a minority of a population, while they have a significant impact on large-scale economies, such as national or large geographical regions (the USA, European Community, Japan, Hong Kong and Taiwan).

Low-level entrepreneurs are of the kind presented by Israel Kirzner's "alertness" approach to entrepreneurship (1973), which focuses on imitation. In this class of entrepreneurs it is not the big innovative ideas that are in focus, but low product novelty, and the re-allocation of the factors of production. For Kirzner it is not technological innovation which is the crux of entrepreneurship, but about being alert to discover profit-making opportunities, that is, spontaneous discoveries to make money. Gunning (2000) offers a useful summary of Kirzner's theory of entrepreneurship. Kirzner's definition "is commonly adopted by emerging economies in an attempt to catch up to more developed nations" (Robinson, 2002:8). Low-level entrepreneurs are local and small-scale, and the entrepreneurial activity not characterized so much by innovation as by filling a gap in a local market.

This project takes the Kirznerian route, and not the high road of Schumpeter. Our operational definition of entrepreneurship is localized to include anyone starting a new neighborhood business to meet a local need. It is not Schumpterian novelty that we are concerned with, but filling a gap by replicating business ideas that have been successfully implemented in other locations.

The broad context within which this research was conducted is within the framework of social activism. Self-generated economic activities in poorer communities are mostly limited. Without getting involved in the critical debate whether ICT might contribute to the economic empowerment of such communities, for the purpose of practical implementation, it was assumed that whatever the answer is to this question, it is a worthwhile exercise to expose this community to the possibilities and potential of ICT. Being researchers as well as social activists, our basic driving value is doing something rather than nothing in order to equip the poor with self-empowering tools.

Participation in the PAR Approach

Initiating, deploying and implementing Information and Communications Technology for Development (ICT4D) projects in developing communities has proven to be very challenging as shown by the large number of unsuccessful projects over the past decade. Such failures are often not reported. These projects rely on donor agency funding, and in order to ensure continuous funding, reporting often highlights the positive experiences. In South Africa, telecenters in particular have been hugely unsuccessful (Snyman and Snyman 2003). The situation has not changed over the past decade. These failures have been described by Heeks (2008) as suffering from the limitations of what he calls the first phase of ICT4D. Participants in the field of ICT4D have realized this and sustainability has now become an important element in project planning. Heeks calls this more recent approach ICT4D 2.0, which not only refers to newer technologies (such as social media) but also to different approaches to managing projects and initiatives.

Participation in itself is not sacrosanct however. The term has been used for a variety of approaches as an easy solution to the criticism of top-down development projects. There are levels of participatory approaches, which vary from "co-option" to "true participation" where local people and development workers operate as equals. Sherry Arnstein (1969), a social worker, working in the area of citizen participation, proposed a ladder identifying eight levels of participation, which we number for the purpose of easy referencing:

- Manipulation

- Therapy

- Informing

- Consultation

- Placation

- Partnership

- Delegated power

- Citizen Control

The first two rungs (manipulation and therapy) essentially are non-participatory: they are flawed efforts that substitute for real participation, since in reality they aim to cure or educate the participants or the public to 'realize' that what the power holders propose needs to happen.

The next three rungs form important steps towards genuine participation but lack the characteristic of enabling decision-making power by participants. They are described as tokenism. "Informing" too often constitutes one-directional communication; no feedback channel being provided. "Consultation" provides participants with a platform to express their views, but no guarantee is given that these views will be taken into account in the decision-making process. In "Placation" participants will be formally consulted, but decision-making power still exclusively lies with the power holders.

Rungs six to eight can be interpreted as proper participation or proper citizen power. "Partnership" allow participants to truly negotiate with the traditional power holders. Decision-making responsibilities are shared. In both "Delegated power" and "Citizen control" the have-nots hold the largest share of decision-making power. "Citizen control" extends this since the participants here also hold full managerial power.

Bradley and Schneider (2004: 9) also describe different levels of participation, depicted in a scale of participatory approaches, from extractive to empowering. Rapid expert analysis, questionnaires, and key informants are put in the extractive methods category. Under the intersection of extractive and empowering, Bradley and Schneider write that "Opinions are shared, but power is not" and "Empowering methods (are) used for extractive purposes". Empowering methods are in-depth, joint analysis, learning and actions, as well as visual diagrams and group discussions.

Expressed informally, PAR is about "making a difference" - not what the implementers think that "making a difference" entails, but informed by the participating community, or more precisely, their representatives. Through conversation, mutual understanding and agreement is reached about what the appropriate ICT implementation would be. Conversation does not mean negotiation. In negotiation, parties compromise based on their potential power, which has the possibility of unequal power relations. Conversation is a two-way dialogue, and in the case of PAR, of ideal equal conversationalists, but driven by the community rather than by the initiators. Hence in PAR the community is the power player, and the implementers are in the service of the community.

Ideally, but not very realistically since implementers are almost always project funders and initiators, the only power implementers have is technical knowledge of ICT systems - and of course theories and models of knowledge. Such knowledge-power is shared, not for the sake of gaining control, but to serve; to suggest technologies that will enable the participating community to reach whatever goals they might have. The assumption is that ICTs deployed through a participatory approach will benefit communities by more accurately reflecting the actual needs of community members, rather than the perceived needs of external researchers. PAR therefore requires a significant degree of collaboration between various internal and external stakeholders: researchers, community representatives, and implementers (which may be a government, a donor agency, or an NGO). All parties should learn from the project. Communities will learn new technologies and organizational practices, while researchers will adapt their hypotheses and theories by drawing on techniques such as grounded theory (Baskerville and Pries-Heje 1999; Gregory, 2010).

Interpreters of ICT4D projects have identified a number of challenges associated with participatory approaches and reflect similar issues to those identified in the field of development studies. Bailur (2007) found that villagers lacked time to participate in a community radio and IT project in India where other priorities are more critical to their daily survival. Frohlich et al (2009) report on a research project in India that sought to democratize content creation and pursue a user-centered design approach to the creation of digital stories on a camera phone. Some stakeholders in the project questioned the quality of content being created by community members and sought to take greater control over the process, whilst the selection of participants became a political issue, pointing to a need for deeper recognition of power distributions in the community. In many cases, participation is used to co-opt community members where external actors (consciously or unconsciously) limit the scope of community responses and actions (Bailur, 2007). In reality, participatory projects are typically still initiated by outside actors and therefore take place within the context of a significant power imbalance. Prominent ICT4D and development scholars such as Avgerou (2010) have emphasized the importance of a more politically aware, critical perspective on participation (also see Hickey, 2005).

The Zandspruit Community

The Zandspruit informal settlement located in the north-west of Johannesburg (South Africa) has an estimated 42,500 inhabitants (Maluleke Luthuli and Associates, 2008) of which 26,250 are in informal households and 16,250 in formal households. The population growth rate of the informal households is estimated at 17% per annum. According to the latest available formal figures (the national Census of 2001, as the 2011 Census reports had not been released at the time of the research) the area mainly houses men between the ages of 20 and 39, which suggests that the population predominantly consists of migrant laborers. In general the residents' educational levels are low. Twelve percent have received no schooling, 27% completed primary school, 50% completed secondary school and 11% obtained some form of higher education (6% a diploma and 5% a degree).

Zandspruit is a relatively stable community in that three quarters of its population have lived there for five years or more. Formal unemployment in the community is high at 28%, but informal trading seems relatively active compared to other known regions, although no formal analysis was done on this. On average, based on the very old 2001 Census figures (no recent figures could be found), individual income within the Zandspruit Region ranged between R1600 (US Dollar 190 approx., depending on the exchange rate) and R3200 (USD 380) per month. According to Euromonitor International (2012), South African household incomes (on the lower end of the scale) increased by 14.4% on average over the decade period ending 2011. If this is also true of individual income of members of the Zandspruit community, income at the time of the research project ranged from R1824 to R3648. Euromonitor gives the poorest 10% a household income ofUSD427. A large number of households (more than 1000 of the 6537 households recorded in 2001) reported no income (Maluleke Luthuli and Associates, 2008). Whatever the exact numbers, income is very low and at subsistence levels.

As with many other similar communities in South Africa, there is limited access to ICT services beyond mobile telephony and a number of smaller (two or three seat) and a larger (eight seat) internet café. There is no community radio station serving the Zandspruit community directly. As far as possible, the project looked to leverage existing technologies within the community, including mobile telephones and a Digital Doorway installed at the Emthonjeni Community Center (Digital Doorway, no date; Stillman et al., 2012). The Digital Doorway is a robust computer kiosk, based on the hole-in-the-wall concept (Mitra 2003), with educational content and applications designed to be very rugged and low-maintenance in order to be deployed for public access (Smith, Cambridge and Gush, 2006).

Zandspruit's Socio-Political-Techno-Economic Environment

Except for one participant, all involved in the project were from the Zandspruit community. Some of the participants were also involved in the running of the Emthonjeni Community Center where the majority of PED workshops were held. Emthonjeni is socially situated between two relatively distinct sections of the community, and funded by religious organizations (predominantly Christian churches) and NGOs rather than by government or by community members themselves. Emthonjeni might be physically "embedded" in the community, but being funded externally, it is not "owned" by the community, and thus to some extent it is politically and socially separate.

A significant number of government departments, external NGOs and researchers from various universities are active in the community. As a result, there is some degree of fatigue experienced by the community, being over-exposed to all these external players, especially as all this involvement has led to very little socio-economic impact, despite many promises. The Zandspruit community has had several civil protests because of poor infrastructural service delivery. The community is dissatisfied with government bodies. One participant noted (reaffirmed by other participants) that conducting research - as participants in our project were required to do - is a politically sensitive issue and can be dangerous. It was pointed out that interviewing people in the community about possible solutions to local problems might create expectations, and if not realized, might lead to further dissatisfaction. Early on in the project this was identified as a risk. Through discussions with participants the project was de-politicized, while the research team emphasized the 'neutrality' of the project by making no promises, and by making explicit that what is important for us is to better understand their lives, as well as by inviting community members to attend the "needs analysis" presentations. About fifteen interviewed individuals attended the presentations.

Finally, whilst there is relatively limited access to ICTs in the Zandspruit community, there are nevertheless a number of existing information and communication technologies and services in use within the community. There is a free service provided by the Digital Doorway, mobile phone access is available through paid services offered by national mobile operators, and mobile phone devices and SIM cards are readily available. Yet, there is low local ownership, access to, and understanding of the technical and business aspects underpinning these services. Due to the lack of understanding of the full potential of ICTs and related business opportunities, there was relatively little interest in the creative appropriation of specific technologies or technology features to serve specific community needs. Most of the suggested business ideas considered only the very basic and general use of ICTs.

3. METHODOLOGY

Several qualititative methodological tools, such as formal and informal discussions, interviews, brainstorming and group interaction were used. The main methodological paradigm used was Participatory Action Research (PAR).

Participatory Action Research

The research team was sensitive to the shortcomings of top-down approaches, and as change agents followed the guidelines of Participatory Action Research (PAR), operating "from the middle" (Stoecker, 2005: 47). However, the research team, with ample experience of working with such communities, was also well aware that communities in developing regions (at the so-called bottom of the pyramid) often do not have the required knowledge or skill sets to act as change agents, and therefore needed to be equipped to participate effectively in the project. Such knowledge also includes knowledge about what it means to be active participants.

One major drawback of earlier ICT4D approaches was that many projects were implemented from the top downwards. Donor agencies, governments and others in positions of power decided what communities needed without performing needs analyses or consulting with communities. With the move towards ICT4D 2.0, more inclusive methods of project implementation and management such as Participatory Action Research (PAR) have become significant.

Action research may be a relatively novel approach amongst ICT4D practitioners and researchers, but the method has been in use amongst development scholars, business analysts, and social scientists for more than half a century. There is no single definition of action research, as pointed out by Cronholm and Goldkuhl (2004), who approach the method from a business perspective. They state that "action researchers are researchers that intervene in a business change process." (2004:47). Action research in ICT is not limited to business processes, but may be applied to any ICT project, or product development, such as community radio and internet cafés, or mobile telephony applications. ICT4D is not only interested in business processes, but also in the social domain and knowledge and skills distribution.

Participatory Action Research was introduced to counter the difficulties of quantifying human behavior as attempted by scientists within the framework of positivist science. PAR as applied in this project is a qualitative approach (Creswell, 1998; Reason and Bradbury-Huan, 2001; Whyte, Greenwood and Lazes, 1989).

One of the major originators of PAR was the Columbian sociologist Fals Borda (1925 - 2008) who encouraged the adopting of a perspective on problems from the periphery or bottom-up (Borda, 2001). If researchers one-sidedly influenced the kind of ICT system deployed or managed, we would be imposing a top-down approach. The "target" audience or community for whom a system is designed or implemented should be actively involved in the technology design and operation. This involvement may be on many different levels, and in any or all of the phases of a project including, ideally, at the project conceptualization phase. Mostly due to time and cost constraints, such detailed involvement is not always possible in practice. It should also be obvious that entire communities cannot be involved, but preferably legitimate representatives. In many cases engaging with a community involves "working from the middle" with intermediaries or brokers bridging between researchers and research participants. Selecting representatives is a complex process, but it is a necessary approach for community involvement. As long ago as the 1970s Manfred Max-Neef (1982/1992) identified this as a critical issue for development projects.

In ICT4D the importance of community participation is also touched upon by, among others, Bala (2011), who argues that relationships and trust between communities and other role players are essential for success. Ramírez (2011) argues that even measuring the success of a project should be participatory. These ideas link up with a more social approach to ICT projects (in line with the notion of ICT4D 2.0) as opposed to the more classic technologically-deterministic approaches of earlier ICT project implementation. More recently the trend has been that researchers are skeptical about the "universal" benefits of ICTs and seek out the human factors affecting the sustainability and impact of ICT4D projects (Avgerou, 2010).

Within the PAR framework there is a wide range of available applications and tool sets, and as mentioned in the Introduction, PRA (Cavestro, 2003), RRA, IDEO, EAR (Tacchi et. al., 2007) toolkits have been used.

4. THE PED APPROACH

Building Entrepreneurship Through Participation

The PED project pursued a relatively radical participatory approach to ICT services development within a marginalized community. The approach sought to overcome many of the challenges of traditional (and existing) participatory methods to ICT project implementation. The PED project aimed to develop ICT-based solutions to community problems by stimulating entrepreneurship amongst community members -- i.e. to develop awareness of entrepreneurial opportunities, based on needs assessment by a selected group of community members. The project may have been facilitated and initiated by outsiders, but it was completely shaped and implemented by the community.

It was designed to facilitate real participation by following empowering methods in order to achieve rungs six, seven, and eight of Arnstein's participation ladder (as mentioned previously). Possible ICT solutions in this context could be completely novel ICT applications, or an adaptation or application of existing ones that would benefit under-served communities. First, by adopting and promoting a participatory approach to service development, the action researchers sought to ensure that the services accurately reflected the needs of citizens in the area, and thereby ensure sustainability through ongoing demand. Second, by stimulating a strong entrepreneurial, 'business' orientation to service development, the project aimed to incentivize participation (and bottom-up needs identification) by local actors looking for a potential source of income/ employment whilst also ensuring long term financial sustainability of the services developed when initial donor funding is completed.

The PED Project

As mentioned above, a PAR method was followed. During the lifetime of the project, continuous sensitivity to the bottom-up approach was important - to such an extent that the community participants performed the community needs assessment, analyzed the results and were part of a creative participatory idea generation session, as well as further developed - and in some cases implemented - those business ideas. The project sessions themselves were also conducted according to participatory principles.

The community nominated participants who, after receiving some training, created their own list of possible ICT services that could be deployed for the benefit of their community. Participants were exposed to participatory methods as well as to possible ICT solutions as inspiration for innovation, and were guided through a process of business development including needs assessment, business idea generation, business modeling, feasibility analysis, and business plan writing. Additionally, participants were supported in establishing their own ICT businesses to meet the needs of the local community.

This project, designed by Ungana-Afrika in close consultation with the Meraka Institute and Monash University, used participatory methods to facilitate bottom-up innovation and local ownership. The PED project employed a participatory approach on two levels: the participants used participatory methods to include other community members in their ICT needs assessment and Ungana-Afrika employed participatory methods in working with the participants to collaboratively identify and develop business ideas. This approach resembles (and was to some extent influenced by) the Living Lab philosophy (Følstad 2008).

The conceptual process flow followed in this project consisted of two main stages:

- Development of needs-based business ideas (phase 1-3 below)

- Incubation of business ideas (phase 4-7 below)

These two stages were further sub-divided by the project team into the following 8 phases:

Stage

Phase 1: Contextual Analysis

Phase 2: Needs Assessment

Phase 3: Participatory Idea Generation

Stage 2

Phase 4: Conceptualization and Business Modeling

Phase 5: Feasibility Study & Analysis

Phase 6: Business Plan Development

Phase 7: Start-Up & Implementation Support

Phase 1: Contextual Analysis

The first phase of the project included site selection (Zandspruit was chosen because of the Monash University link to this community); gathering of demographic data on the area; identification of other initiatives and organizations operating locally; stakeholder identification; meetings with local stakeholders (Monash community liaison and community leaders); the search for potential participants with entrepreneurial potential and ICT knowledge (suggestions for several individuals who fitted this description were provided by different community leaders); and ultimately the selection of the participants by Medupe.

Medupe combines an ICT training course (based on the International/European Computer Driving License) with business skills training. A total of sixteen people, with slightly more women than men, had taken these classes. All members of Medupe were free to apply to join PED if they wanted to, but were in no way obligated to do so. Based on their response to an application form that asked them about their motivation for joining the project they were included as PED participants. In our selection, gender balance was an important criteria for selection. Finally a total of nine participants (five women and four men) were identified for the project.

Phase 2: Training for Community Needs Assessment

In a workshop PED participants were trained on how to use participatory methods for ICT needs assessments. A diverse mix of methods was taught by drawing on the techniques previously mentioned (PRA, RRA, IDEO and EAR). These methods were converted into practical guidelines in the form of a hands-on reference manual (Van Gendt-Langeveld and Makuru, 2011). The logic behind the choice of this approach was to enable the project to operate on principles of equal footing and collaboration with community members and to ensure that the outcome was not one-sided but rather of mutual benefit. The benefit to the community was envisaged as being socially relevant ICT services, as determined by community members, and entrepreneurial opportunities. These members, the participant entrepreneurs, were to identify viable business opportunities within the community, while the role of the external researchers was to facilitate the process of empowerment and knowledge transfer on needs assessment methods (and business development) and eventually develop new models for ICT-enabled solutions specifically geared towards the identified opportunities.

Participatory methods were also used in teaching the methods workshop. For example, a method was used to facilitate "interactive introductions" (UNDP, 2006), which is an exercise that demonstrates the value of listening. In this workshop the participants also received an inspirational talk on social entrepreneurship; 'the possibility of doing good and living well', and on their power as individuals to achieve.

To ensure that participants had sufficient knowledge of socially beneficial ICT possibilities, they were sensitized to the broad potential of ICTs in general; and, because of their local potential, of mobile applications and the Digital Doorway (DD) option in particular. The intention here was to give the participants a frame of reference in order to stimulate their innovative thinking while performing their community needs assessments.

Two workshops were held to teach participatory methods for needs assessment. PED's hands-on participatory methods manual (Van Gendt-Langeveld and Makuru, 2011) provides details of 43 different methods. It was distributed and the participants practiced a selection of methods. The workshops also covered explaining and practicing the participatory attitude of observing, listening and non-interference, and dealing with gender and as well as with sensitive political contexts. PED's participants decided on their own needs assessment goals and drafted detailed plans on which methods to employ, when and with what means, to reach those goals. One-on-one mentoring sessions supported the participants during the two-month period when they were creating and executing their individual Needs Assessment Plans. The one-on-one mentoring sessions included site visits, and telephone calls initiated through Please Call Me (PCM) messages in order to minimize costs for the participants.

Phase 3: Participatory Idea Generation

In this project the participants were supported in developing entrepreneurial ideas that they could implement in their community. The creative process in which business ideas are crafted from identified needs can be stimulated by non-steering and non-critical means, but encouraging participatory approaches. In PED this was done in Phase 3, where the ICT needs assessment results from Phase 2 formed the input for a participatory business idea generation process involving individual potential entrepreneurs and Ungana-Afrika staff. During a workshop the participants shared their Needs Assessment results and partly individually, partly collaboratively, they subsequently generated business ideas. Adaptations of the following participatory facilitation methods were used from the IDEO toolkit: 'participatory co-design', 'empathic design', 'find themes', 'extract key insights', and 'create opportunity areas' (IDEO, 2008). In the empathic design element Empathy Maps (Gray, Brown, Macanufo, 2010) were used to map out the needs, desires and environment of target customer groups. The goal of this process was to truly understand community members' needs and use this knowledge to envision beneficial products and/or services.

Phase 4: Conceptualization and Business Modeling

Once ideas were discussed, a quick screening of the potential for the generated business idea was conducted in the Conceptualization and Business Modeling stage. The techniques and methods used in this phase were explained in a workshop setting, whilst participants were assisted in applying them through one-on-one engagements. One of the main tools employed here was the Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder, 2010). This tool, consisting of nine building blocks, involves the mapping out of a first vision of the business model, based on the needs identified in the previous phase.

Phase 5: Feasibility Study & Analysis

Participants conducted their own feasibility study and analysis, which consisted of the following components:

- Environmental Analysis: External factors impacting on the business model were assessed in order to understand how environmental dynamics could affect the business. These factors include market forces, industry forces, key trends and macro-economic forces.

- Pricing and Market Determination: The pricing of similar products and services in the market was analyzed, and a target price was determined for their own offering set, based on its differentiation value and the price sensitivity of their own customers.

- Legal and Operational Structure: The most appropriate legal framework for the enterprise was discussed; whether it was to be operated as a sole proprietor, partnership, or some form of company. The operational structure was also determined, along with key personnel requirements.

- Financial Analysis: Financial spreadsheets were prepared to evaluate the financial potential of the business. Sales projections and cost structures were used to do a break-even analysis and cash flow forecasts, and to determine funding requirements and identify possible funding sources.

- Technical, Social, and Management feasibility: This was assessed where applicable and included the social and technical context of the future business and potential tensions as well as the background and suitability of the people placed in management positions.

- SWOT analysis: A Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis was employed to evaluate all aspects of the business idea, identify risks, and draw conclusions in terms of overall feasibility.

For each of these components, tools and tips were provided on how to go about generating the information.

Phase 6: Business Plan Development

Information generated through Phases 1-5 provided all the necessary input for the participants to produce their business plans. In a workshop Ungana-Afrika demonstrated its business plan template which guided the participants through the business planning process. Ungana-Afrika's one-on-one mentoring continued in this phase as well.

Phase 7: Start-up & Implementation Support

The participants were, and at the time of writing still are, supported with any difficulty they encounter starting their businesses.

5. FINDINGS

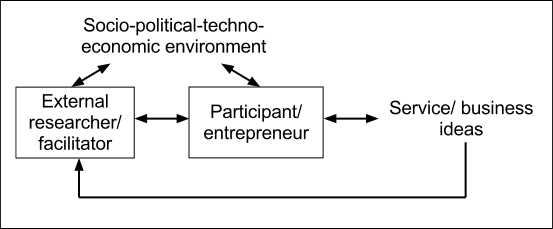

Data was collected through three different questionnaires at different phases of the project. The main purpose of the questionnaires was to monitor and evaluate PED's approach. Data was also collected as comments by participants in a feedback workshop, and from personal reflections of Ungana-Afrika researchers involved in facilitating the PED process. The findings can be presented in three main categories: the relationship between researcher/facilitator and participant/entrepreneur; the relationship between participants/entrepreneurs, researcher/facilitator and the wider environment/potential service users/community; and the main outputs of the process including the evolution of business or service ideas in response to the environment and the PED process.

Relationship: Researcher/Facilitator and Participant/Entrepreneur

Through its community engagement initiatives, Monash University played a major role in community liaison. At a meeting with Zandspruit Community Leaders, Medupe was selected as a good source for participants with sufficient prior ICT knowledge. It was assumed that their relatively strong ICT interest and level of proficiency (ICDL/ECDL) would enable the participants to make suggestions on the type of required ICT applications. Results of the baseline evaluation showed that the participants rated their own ICT knowledge as adequate. On a five point Likert scale, six out of nine rated their knowledge as Average, one as High, and one as Very High, while one did not answer the question. The community regards most of Medupe's members as young/future community leaders which provides them with easy access to a broad base of the community and an advantaged position for performing a community needs analysis. As such they formed good 'intermediaries' (see section on Participation in ICT4D projects).

The Medupe members were invited to participate in the PED project and twelve applications were received, of which nine joined the project while three applicants were unable to commit the time and effort required. The average age of the participants was 27.5 years. About half of the participants had finished high school (Grade 12), the remainder had completed Grade 11. Only one participant had any entrepreneurial experience. Eight of the group participated through all the phases of the project, although some completed only part of their (extensive) business plan. One participated until phase three, but then had to drop out due to other obligations. Only one participant was not a Zandspruit community member. Five of the participants were female, four were male. Participants generally spoke seTswana amongst themselves, so English was at best a second language. Some of the participants were involved with the Emthonjeni Community Center and were involved there in providing various social services to the community.

Results and Responses

The goal of the PED project was the development of entrepreneurial capabilities and culture amongst participants, while the primary envisioned output was generating specific business ideas that could be targeted for more detailed elaboration and commercialization.

With regard to entrepreneurship, participants acknowledged several benefits. For example:

- At the beginning most [of us] thought 'I don't want a business', but now [our] attitude is different.

- Now there is light, I might want to start a business

- We can use what we learned, not only by starting a business ourselves, but also helping others who want to start a business

- I learned from the Needs Analysis that you have to think of the people you are working with

All respondents indicated that the PED process had helped them to come up with their business ideas.

The scope of topics of conversation between participants was broad, and covered general business concepts, and as such stimulated ideas beyond ICTs. In one session, participants discussed types of possible businesses and one respondent noted that:

- Through the Needs Analysis I realized I did not want to run an internet café

Even though this self-discovery in a sense defeated the ICT-entrepreneurial angle of the project, at least in a more general sense it opened up vistas for participants. Some way through the project, one participant felt that not finishing high school severely limited her potential, so she went back to school.

Despite the participants having had exposure to ICT (their ICDL/ECDL training using regular desktop computers and via their cellphone), the lack of in-depth understanding of ICT was a major limitation on their ability to make suggestions and identify opportunities for new services. The implication of this is that for generating truly innovative ICT applications, entrepreneurs require ICT knowledge of much more depth and breadth than was possible to convey during the lifespan of this project.

During feedback on the ICT sensitization workshop one participant suggested that "the information on ICT was too complicated". The diversity and complexity of the technologies being used in the community was therefore a challenge for the participant-entrepreneurs. This resulted in a dilemma. If researcher-facilitator input was too intense and involved, the proposed solutions might not have reflected the real needs of the community. A very fine balance is required to lead community participants to useful solutions, but those solutions cannot be created by solely by the researcher-facilitators, otherwise the project would end up following the top-down approach, defeating the purpose of following a participatory approach in the first place.

Responses to the question "What do you think the Digital Doorway can do?" were generally positive in the initial phase. Here are some examples of suggestions from the participants (copied here without language correction):

Views on the Digital Doorway during the initial phase of the project:

- It can help develop computer skills

- It can help the other people to develop in terms of ICT

- It can help the community via information of anything they search for

- It helps when you want to do research or for playing games etc.

- Advertise Government bursaries, jobs (info) including the universities and private sector

- Enhance people's knowledge regarding technology.

- Entertainment

- Help educate computer literate people

- Help with communication, research

Views on the Digital Doorway during the mid-term evaluation were the following:

- It can develop people one on one and help them to understand what they are doing and to help the kids with their homework

- Research is the only one to assist us

- Can help the community with information, service provided by government, entertainment

- Can help people to do research about their business or anything that they want to research

Interestingly, about half the answers relate to developing skills for using ICT; which incidentally is one of the primary goals of the Digital Doorway project.

Participants viewed the potential use of mobile phones during the initial phase of the PED project as follows:

- Mobile phones can be used for internet transactions

- Networking and communication

- Calling, networking with people and also Google information

- Internet & to contact friends, family and a lot more

- SMS info

- telecommunication, Internet, banking

- sending emails, sms, direct calls

- sms, emails

Views on mobile phones during the mid-term evaluation were the following:

- Communication and knew to send messages to the other and use network communication

- To communicate

- Interaction e.g. communication, research

- Internet banking, communicating, Facebook-ing, MxIt-ing, emailing documents

Generated Business Ideas

Participants were required to generate business ideas on three occasions during the lifetime of the project. The first was as part of the baseline questionnaire, taken before the participants had performed their needs analysis. The second was part of the mid-term evaluation which directly followed the needs assessment phase, and the third occurred after the needs analysis and business idea generation workshop.

The possible business ideas collected before the needs analysis was done, as well as those reported by the participants right after they had finished performing their needs assessment, revolved around popular and commonly known ICTs. No novel suggestions were made. The suggestions were on the level of technology propagation (Perez 2002) rather than high-level entrepreneurial innovations of the Schumpterian kind. Suggestions focused on the ICTs themselves, rather than on possible services that could be rendered by ICTs. After the business idea generation workshop, which seems to have opened the minds of participants, almost all business ideas now reflected community needs in general. Beyond ICT-specific businesses only one idea (internet café) was ICT specific.

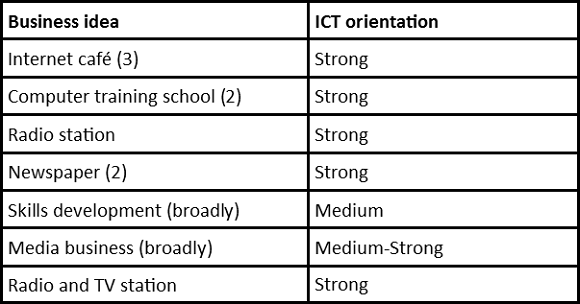

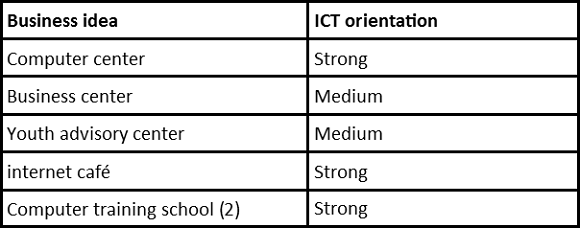

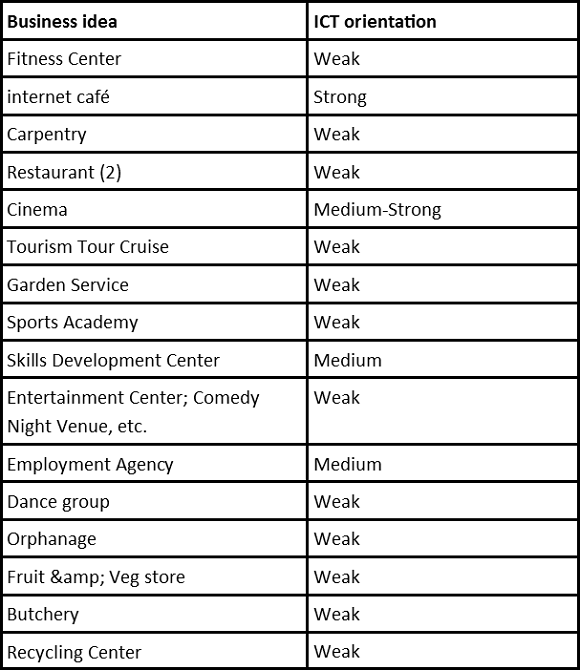

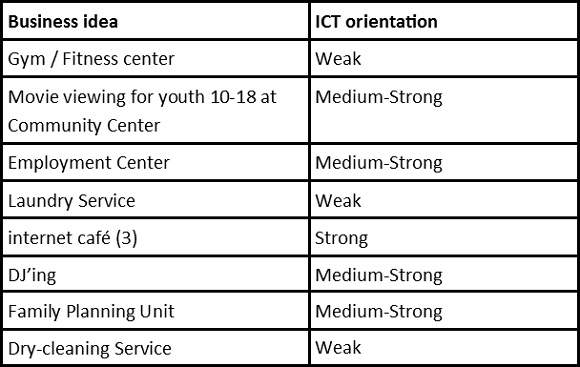

The following business ideas were created. The numbers indicate the number of participants suggesting the kind of business. The ICT orientation column indicates whether the business would predominantly be an ICT business (strong), ICT-dependent (medium), or the core business not being ICT-related, but supported by ICT (weak).

Initial set of business ideas

The initial set of business ideas had a strong media focus. Media is driven by ICT, but the core business of media is information rather than ICT itself. However, an entrepreneur could make money by creating the necessary ICT channels and support. Skills development does not necessarily imply ICT skills, although ICT could be used in the development of the skills.

Intermediate set of business ideas

With the exception of ideas relating to a business center and a youth advisory center, halfway through the project the set of ideas were still strongly ICT focused, and not yet on the use of ICT as support tools.

Final set of business ideas

The final set of business ideas is surprising, and indicates that participating community members do not consider ICT as valuable tools to assist in meeting their primary needs.

Apart from the internet café, cinema, skills development center and employment agency, none of the business ideas relate to ICT. From an expert ICT position, we would have expected many more proposals of how ICT could assist even in the proposals for other, non-ICT kinds of businesses. For example, surprisingly, no proposals were made along the lines of, say, using ICT to show different kinds of exercises in the Fitness Center or exercise class schedules, or the use of ICT design tools for Carpentry and even 3-D printing. The exception was for the Fitness Center business plan for which office IT equipment and internet access were budgeted for.

There were, however, no explicit references to innovative ways in which ICT would be utilized for these businesses. For example, the suggestions for the Tourism Tour Cruise and the Garden Service did not include any reference to ICT, such as web-presence for these businesses, or of ICT as management or business support tool. As there are no gardens in Zandspruit, such a business would serve communities in other neighbourhoods where there are gardens. The only benefit for the Zandspruit community would be income generated elsewhere, while the service itself is of little direct value to the local community. The very limited extent of such suggestions points to a lack of proper understanding of the power of ICT and of business processes in general, most likely due to the fact that participants' ICT skills and business knowledge are not advanced, and their knowledge restricted to the user level.

PED's spreadsheets for financial analysis that were distributed for the purpose of feasibility analysis are now used by one of the start-ups.

Business Ideas Eventually Implemented

An internet café was established, the implementation of the fitness center is in progress, and movies were shown for children at the community center. The other proposed businesses are not ICT-related (although by some stretch of imagination, DJ-ing might be squeezed into this mold if a computer is used for the playlist).

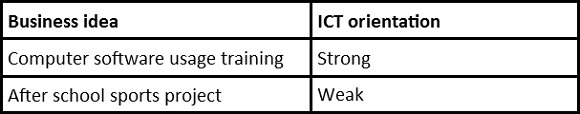

Additional Business Ideas Implemented After Completion of The PED Project

Since the completion of the project the following ideas were generated as business opportunities. The "Computer software usage training" idea which was implemented is aimed at skills development.

6. DISCUSSION

The aim of the PED project was to encourage (and utilize) a relatively strong and radical participatory approach to ICT service development. It was important for the project to ensure that the proposed technologies and services met the needs of citizens and could lead to sustainable solutions run by local entrepreneurs. This would be assured by encouraging the community-based exploration of ideas from the bottom-up, and to incentivize participation based on possible economic benefits, whilst ensuring long term financial sustainability when initial donors complete ther funding.

Unexpected consequences of the project included self-discovery and empowerment (e.g. one participant recognized her short-comings and decided to go back to school), and an increased entrepreneurial drive (by realizing that starting a business does not have to be an obstacle).

The expected outcome, that participants would generate novel ideas for implementing ICT solutions was not achieved. Regarding possible businesses, ICT was not regarded by participants as a primary tool that could assist in meeting the needs of the community. Generated business ideas focused on other perceived needs relating to health, sport, entertainment, jobs, and basic food supply shops (e.g. butchery, vegetables). Perhaps due to a lack of an understanding of ICT and of business, there were no suggestions on how ICT could serve in a supporting role for these possible businesses.

From a technology perspective it was found that participants were unable to effectively identify innovative opportunities related to ICTs. The expectation that ICT solutions would be proposed by participants for the many problems in the community was also not met. They seemed unable to relate the needs and demands of the community to innovative ICT solutions. Even though this project took the Kirzner's low-level definition of entrepreneurship as the point of departure rather than Schumpeter's high-level definition, results were nevertheless somewhat disappointing as apart from the internet café no ICT-specific opportunities were identified. There seems to be a lack of understanding of and disconnection from the broader ICT techno-business ecosystem.

In order to bridge this gap, a longer-term exposure to the potentialities of the broader ICT and business ecosystem environment is required before appropriate, workable ideas can be generated. However, there were outcomes that indicate individual (rather than social) empowerment, a more needs-based/ service-oriented outlook, and increased business acumen in our participants. After completion of the project, participants continued to use the skills and tools gained through the PED process, often in ways not previously envisioned.

Examples are:

- One participant is now pursuing a degree. She has used the community research processes as part of her studies, and found the market research aspects particularly useful.

- Prior to the project, innovative community members at the Emthonjeni Community Center would start projects as they themselves perceived them, but now they request input from the target members. An after school sports project was established based on community needs.

- Acquiring budgeting knowledge was useful as participants realized that short-term, such as month-to-month financial budgeting is not wise, and there was a shift to much longer term planning.

- One participant indicated that she felt more empowered, and had a stronger sense of self-esteem as a result of implementing the PED processes. When talking to people about her projects, she feels that people think "You know what you are doing!".

- Another participant has started his own business training people to use computer software. He is using PED's financial spreadsheets in his business.

From an entrepreneurship and idea generation perspective, it is clear that as participants became more familiar with the PED process and accepted the open nature of the engagement, they were able to explore a more diverse mix of business opportunities. This is a potentially valuable lesson in that it highlights the value of open participation in stimulating true entrepreneurship and identifying a wider mix of ideas than those initially proposed or suggested by the researchers/ facilitators. Although many of the ideas had a low ICT orientation, the PED process seems to have contributed to the development of an entrepreneurial awareness and capabilities which potentially feed into other existing and future projects, such as the internet café and Emthonjeni's activities. Nonetheless, this project also highlighted the difficulty in offering apparently strong ICT users an opportunity to become ICT entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, the project opened the minds of participants beyond the specific goals of the project.

From a politico-economic perspective, the adoption of an 'entrepreneurship' and strong business orientation tends to assume that the development of services takes place independent of the social and especially, political context. However, as participants observed, researching a new service has political undertones and can be potentially a politically explosive exercise. In many cases, the low income of citizens in marginalized areas (and especially high security costs to safeguard against theft) also means that ICT businesses may never be financially sustainable. Kuriyan and Ray (2008) examine similar contradictions involved in the "profit in the BoP" (Bottom of the Pyramid) approach to ICTs.

From a research funding perspective, the cycle of funding puts constraints on the efficient implementation of possible positive outcomes. In practice funding is typically available for a relatively short period of time, after which funders require feedback reports. This puts pressure on the initiators and reduces the time available to conduct deeper training and exploration of the technology. This in turn may lead to a focus on implementing the project rather than following the substantial body of evidence provided by the community participants that suggests that sustainability is only possible through strong, long-term participation. PED's participants are still supported by Ungana-Afrika on a support-request basis.

Although the results were mixed, some of the findings were informative. One important insight is that lack of in-depth knowledge is perhaps the most important inhibiting factor for pro-poor innovation and the establishment of innovative business ideas in disadvantaged communities. Complex technologies, such as ICT, require an understanding of their entire ecological landscape before innovative solutions could be generated. Understanding business in general needs to come first before support systems for those businesses could be understood. Perhaps, if the focus of this project had first been on business, as a follow-up, a project more focused on ICT results might have been different. Yet, having followed a phased approach, we think that we have addressed the priority of understanding business first.

Although community members know their local circumstances better than any outsider could, they lack the bigger picture as well as a vision of how ICTs would fit in the local setting.

Another insight is that communities do not necessarily regard their needs as ICT-related, and do not easily discover potentialities of how ICT might assist in meeting their needs. These findings have implications for ICT4D projects. The successful implementation of ICT4D initiatives that might lead to entrepreneurial business requires extensive background knowledge. Programs such as PED are one step in the right direction to equip locals with background knowledge, although ICT background knowledge was not the focus of the project.

7. CONCLUSION

The initial aim for PED (Participatory Entrepreneurship Development) was following a participatory approach, in order to stimulate bottom-up ICT innovation and ICT entrepreneurship in a disadvantaged community. Having completed the project, we have realized that the aim for innovation perhaps was not very realistic. The business ideas generated through the PED initiative certainly do not meet criteria of Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurship nor even the lower level expectation of Kirzner's definition of entrepreneurial imitation, at least regarding ICT-specific implementation. Most suggestions for innovation did not even have an ICT component.

For community members to participate sensibly in generating ICT business ideas, requires and demands levels of knowledge and skills the participants do not seem to have. They need to be business and tech-"savvy" in order to be innovative. The school system in South Africa in general does not stimulate such knowledge, while the quality of schools in informal settlement areas is generally worse than in established suburbs. The World Economic Forum ranked South Africa 133 out of 142 countries for Quality of the educational system and for Quality of math and science education 138th (WEF, 2011). Being entrepreneurial, in itself, already requires advanced skills that the education system fails to provide (Endeavor SA and FNB 2010:7). The deck of cards is stacked against the poor on many different levels. Easy solutions, such as ICT and specifically mobile technologies heralded especially by mass media to be the universal solution to all the problems of the poor, disregard the complexity of community life, and the vast amount of background knowledge and skills required to sensibly make use of ICT.

Even though results are encouraging from the perspective of entrepreneurship stimulation, empowerment, and sustainability of activities, the problem remains that innovation using ICT was not amongst the key results of the project - not even ICT as a support tool for other types of businesses. Strong participatory, entrepreneurial approaches might therefore not be suitable for Bottom of the Pyramid ICT design without also equipping participants with much more knowledge about business and ICT possibilities as well as an understanding of how ICT could support business practices.

Unless the scope of ICT4D projects is extended to include extensive relevant background knowledge, ICT innovation "by the community, for the community" will remain an unattainable dream.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by Monash University, South African campus, and is based on a report prepared by Marjolein van Gendt-Langeveld, to whom we wish to convey a special word of appreciation for her hard work on the project.