Stoecker's (2005b) review of the emerging discipline of Community Informatics raised the question, "Who gains from Community Informatics: the academic, the market or the community?" There are many stakeholders in a community project, such as academia, business, industry, people who live in the community, and community workers. Community involvement and empowerment is seen as central to community informatics, although strategies to initiate and sustain empowered communities have been elusive (Unwin 2009).

Bradley's (2006) vision of Community Informatics is that it increases well-being and the quality of life for all. Many communities do not have the infrastructure or training to develop and engage in information technology. In the first major work on community informatics, Gurstein (2000) observes,

"Community Informatics is concerned with developing strategies for precisely those communities unable to take advantage of some of the opportunities which the technology is providing" (online text).

Within this definition there is a clear role for local communities to become empowered and to engage with technology, thereby having access to information which would increase their communal life experience, and social technology is often seen as a catalyst for social change (European Commission, 2010). De Moor (2008) suggests that for Community Informatics as a discipline, community empowerment may be enhanced though the use of action research within the 'Living Labs model.'

This paper investigates the concept of stakeholder in community projects through:

a) Presenting a case study of an African Living Lab, a community-driven technology project aimed at empowering youth in its locality.

b) Describing the secondary roles of other stakeholders in the project.

c) Discussing factors that helped or hindered the success of the project.

A key concept within any community project is the stakeholder, and there are two classical definitions. First, in capitalist business, stakeholders are those who deposit money in a venture and expect a return (Oxford Dictionary, 2010). A second, broader, definition was proposed by Freemen (1984), as those who had a vested interest and who can affect or are affected by the organisational project.

The difference in these definitions reflects a difference in attitude between those who see development as a business paradigm with definite funding, commercial aims, and commercial ends, and those in civil society who are interested in creating an effective community.

In community development, stakeholder roles are those that 'act' as stewards for the institution. Stakeholders have "a latent or expressed interest in the organization accomplishing its mission or goals and do not see it as something to be mined for personal gain and then discarded when convenient" (Avglin, 2000).

Stoecker (2005a) investigated the planning of research by 'elite' funding groups in a community project and noted that their interaction with agencies and institutions involved a top-down approach. Stoecker suggested that such an approach could cause conflict with the community workers and community members, who may not have been seeking financial or business project outcomes, and who were more passionate about its continuing success. Part of the challenge within Community Informatics is to enable the community to be a major stakeholder in regeneration and the creation of innovative digital technological solutions (Morris, 2006).

A working definition of Living Labs is:

"Functional regions where stakeholders have formed a Public Private Partnership of firms, public agencies, universities, institutes and people, all collaborating for creation, prototyping, validating and testing of new services, products and systems in real life contexts" (Core Labs, 2008).

Living Labs are a real life interactive space where technology, communities, and commercial interests engage in qualitative action research which changes as necessary with reflection and analysis facilitating the generation of working models and theories.

Eriksson et al (2005) identified commercial, technological, and societal actors and their interactions as essential components for Living Lab research. Where technology is new, it may be uneconomical for society and not commercially viable and thereby excluding the broad public from the opportunities offered by the technology.

The aim of Living Labs is to create a collaborative work environment, where:

"integrated and connected resources providing shared access to contents and allowing distributed actors to seamlessly work together towards common goals" (Hribernik, 2005).

Living labs' core belief is community empowerment. As Bergvall-Kareborn (2009) state in evaluating a Living Lab project, "community influence is key".

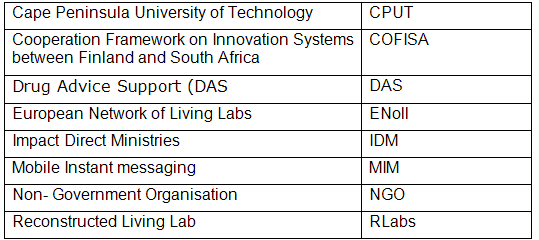

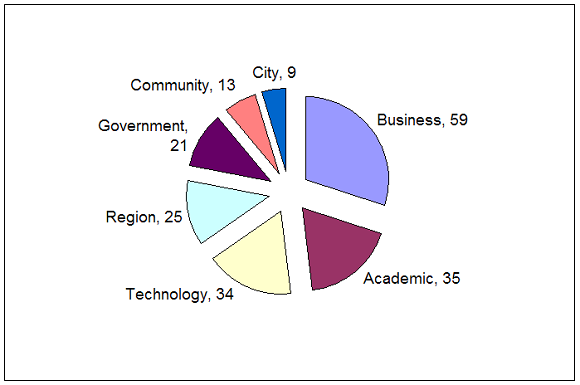

A concept analysis was undertaken of the summary public documentation of Living Labs funded projects in 2009. There were 97 projects analysed, the stakeholders mentioned in the projects were classified under the headings of: Business and Tourism, Region, Government, Community, City, Technology, and Academia. The results suggested that although community is central to the Living Lab concept, partners from the community are named as stakeholders in the project descriptions only thirteen times, less than business, academia, technology, region, and government (Figure 1).

Dutilleul et al (2010) analysed the social dimensions of the European Living Lab. The participation of community or 'users' was perceived to need further investigation; in particular "how can we prevent knowledge asymmetries from making the role of the user in the innovation process a subordinate one?" (p.80). They noted that user interests have not been well researched and identified a number of factors which make user-driven Living Labs difficult to achieve. A second factor highlighted in the article was that the user groups: users as individuals; user mobilisation and user co-operation needs stronger motivation than just the technology in order for them to engage in the project. Thus there was evidence of top-down management in Living Lab practice, rather than an approach to generating community empowerment.

Addressing the difficulty in making the community central to the development process, Mirijamdotter et al., (2006) suggested developing a community-based Living Lab model. Their model is need-oriented, rather than product-oriented, as needs were considered more sustainable, more likely to energise, and more likely to be raised by the community. In this model, the community would explore different ways to fulfil their needs and avoid being monopolised by one business, project, or provider. A civil community group in South Africa became a Living Lab by identifying the community's needs and helping the community address those issues; it is called RLabs.

This case study is explored through the narrative of the founder, his presentations, and documentation from the stakeholders. RLabs' features are unique in the Living Lab model, being community designed, community driven, and with its innovative technology developed at the grass roots level. Athlone is a district of Cape Town and is situated on a region known as the Cape Flats; where RLabs originally started, its community can be described as a Community in Tension due to it being "socially deprived and characterised by violence, drugs and gangsters," (Parker et al 2008).

In 2007, a group of ex-gangsters and drug addicts gathered at a community NGO, Impact Direct Ministries (IDM), with a desire to use their past experiences to improve the life choices of others in the community. These individuals were not a sample of the community, but were social champions in that they were people who were motivated to change the culture of their communities. They had limited academic qualifications but were prepared to take some action themselves and be agents for change in their communities.

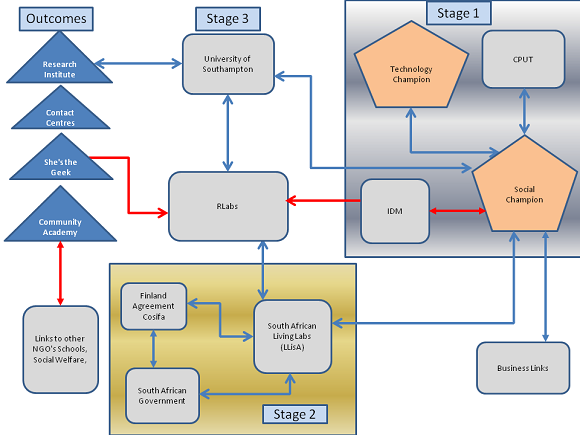

Stage one of the development of RLabs grew out of a collaboration project between IDM and Cape Peninsular University of Technology (CPUT). . Through further links with government and academic stakeholders, in its second stage RLabs piloted action research through the Living Lab model, being the first Living Lab in the Western Cape region of South Africa.

In stage three, RLabs officially registered as a social enterprise and is currently managed by a board of directors consisting of local community members, and by an advisory non-executive board consisting of representatives from business, academia, community, and government agencies. RLabs' three stages of development are shown in Figure 2.

RLabs aims to increase the empowerment, encouragement, and development of community members who may be or are headed for difficulties through the creation, dissemination, and application of knowledge. It aims to do this through the use of innovative ICT solutions to facilitate the health and social care of residents , looking to empower the residents to change their community themselves.

South African mobile phone subscribers in 2008 were 45 million, an increase from the year before. Compared to fixed land-line subscriptions of 4.4 million, it can be seen that the mobile phone is the telecommunication tool of choice in South Africa (Economic Watch, 2010).

According to Nitsckie & Parker (2009:8), "Mobile Instant messaging (MIM) is technology which provides communication between one or more participants over a network or the internet. Instant Messages conversations initially used text-based methods but have recently also added sound or voice, video and images. Extended functionality now includes file transfers, group chat and conference services. Instant Messaging, as opposed to email, happens in real-time". Instant messaging is also very cheap in comparison to text messaging in South Africa.

RLabs developed a mobile instant messenger aggregator that can be used to manage multiple mobile chat conversations, providing real-time support as a counselling medium. The community provided development space for innovation of the new product (Parker, et al., 2010).

Secondary stakeholders were essential to RLabs development. Academia, government, and industry have produced tangible tools, help, advice, and inputs which have enabled the community to achieve RLabs' aims. A summary of the role of stakeholders and their place in the RLabs project are (Parker 2010):

A) Academic stakeholders

The Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT) partnered with Impact Direct Ministries when RLabs started out as a community project. The University of Southampton, UK, and Aalto University, Finland, joined the project with advisory and research support. The academic partners are an important element in providing training to the community in skills which are essential for technological innovation. The academic partners were prepared to invest in people in deprived communities. This collaboration between academia and community is necessary to move theory into practice.

B) South African Government and Innovation partners

The Government of South Africa is leading African technological change. Its aim is that through innovation, communities can address fundamental issues such as health and education, to enhance economic growth and improve the quality of life. The government describes its plan to innovate as different from both the indigenous tradition and the imported Western business models. The Living Lab model was chosen by the South African government, noting 'the start of the project is community-driven' (Living Labs in South Africa, 2009).

Demonstration of the South African government's support for localised innovation initiatives is shown by its partnership with Finland to enhance South Africa's innovation development through the Cooperation Framework on Innovation Systems between Finland and South Africa (COFISA). The overall objective of the COFISA Programme is to enhance the effectiveness of the South African National System of Innovation contributing to economic growth and poverty alleviation. This led to the foundation of the Living Labs in Southern Africa network, of which RLabs was one of the founding members. The initial stage of RLabs, including its feasibility study and business plan, was funded by COFISA. This funding and strong networking was important in enabling RLabs to move to a social enterprise organisation.

The importance of the social champion is highlighted through this project. Unwin (2009) notes that "Successful ICT4D initiatives...require visionary champions who are able to generate the necessary commitment to drive them forward" (p.366). The social champion, a university lecturer was essential in networking with organisations to set up the living lab pilot study and the Living Labs in South Africa (LLisA) network.

C) Business links

By developing technology in-house, RLabs was not reliant on an external product and imported technology. The role of industry in RLabs has been to adopt innovative technological ideas, and to support the piloting and production of the Jamiix platform. The industrial and academic champions were from the local community and were willing to invest in community regeneration. COFISA enabled meetings with international business groups who became important partners in the project.

The following contact support centres using RLabs' MIM solution have been set up and supported from the lab.

MIM has been patent protected and used by projects in Europe, Asia, and South Africa, and brings an income to the Living Lab project which increases its sustainability. In 2010 the mobile counselling application was a finalist in the international Bees Award for best use of mobile social media1 .

The RLabs Academy offers a series of courses to the community including Advanced Social Media, Online Safety and Ethics, Entrepreneurship, and Leadership. RLabs also runs training for the community with classes in social media; as well a mobile phone service for the unemployed in the region is provided through job advertisements by means of text messaging.

RLabs has generated an income through employing people from the community to provide consulting services to other community groups, individuals, and businesses interested in social media for innovation. One of the projects that was developed out of this services and empowerment programme is She's The Geek2 which specialises in the use of technology to empower vulnerable women and also focus on digital marketing for well-known brands.

The RLabs social franchise has been licensed in Asia, Europe, and South America. As well, RLabs partnered with the World Bank at the official social media Innovation Fair in South Africa in 20103 .

Further development plans include establishing RLabs in Brazil, Finland, Kenya, Portugal, Malaysia, Namibia, Nigeria, and Tanzania. Plans for further research and evaluation will include the measurement of community outcomes, including the sustainability of the project.

In areas of social deprivation and under developed educational achievement, such as small communities in South Africa, projects presenting technology alone are unlikely to transform a community (Stoecker, 2005a; Castells, 1996). Looking at the Ikamva Youth organisation in Cape Town, Evoh (2009) noted that

"a combination of ICTs, proper training of teachers and the involvement of community-based organizations such as Ikamva Youth, will help to realize the greatest social and economic returns to investments in educational technologies"

Evoh (2009) goes on to suggest that the sustainability of projects relies on sponsorship from government and private agencies. A major weakness of community empowerment is its dependence on external funding (Schuurman, et al., 2009). Being controlled by those with funding was a situation which the RLabs community wished to resist. It was envisioned that selling its innovations and services to non-government groups world-wide would enable the community to sustain itself. By 2011 this has begun, but the marketing of community developed products has not been straightforward.

Part of the challenge to Community Informatics is to enable the community to be the innovator of new technology (Morris, 2006), and to be the major stakeholder in their community's regeneration. Sustainable change has to be led by the community (Bell, 2004).

In theory, the Living Lab model requires the community to be the main stakeholder. However, the content analysis results of Figure 1 suggested that this is not the situation with the majority of projects. This adds weight to Folstad's argument that co-creation is an ambition rather than a realized approach (Folstad, 2008: p.108).

In its active approach to co-creation, RLabs identified five essential elements as important.

After three years, some of the challenges that RLabs faced and lessons that other initiatives taking a community-driven approach to Community Informatics could learn from are as follows:-

RLabs is testament to a bottom-up approach to social innovation. It supports Stoecker's view that the community is interested in projects and being co-creative in innovation. It also increases the likelihood that Living Labs can provide transferable theoretical modelling that is of use to the field of Community Informatics., Further work is required, however, to ensure the transferability of good practice to other situations.

RLabs has required the community to be the main stakeholder in the project and has sought a sustainable model of social transformation. This fulfils the criteria of Bradley for Community Informatics as how it benefits socially excluded groups. This can only be possible, however, in a social context where governments, businesses, and academic stakeholders are prepared to work with communities in a long-term, sustainable, educational, and capacity-building relationship. Although academia and industry were involved in RLabs, the key academic actors and software developers were from the Athlone community. It would have taken longer for people from outside to gain entry at a level that the community would trust.

For Community Informatics to benefit the community in an empowering way, RLabs has demonstrated that it is important that key stakeholders come from the community as far as possible. Outside stakeholders can assist, train and refine: they can also provide barriers to growth by reducing community capacities or enhance growth by giving opportunities to community members to network in different circles. For sustainable empowerment, however, innovative technology needs to be community driven, designed, and owned. Further investigation is needed as to the groundwork necessary for such a symbiotic relationship to develop.

1 http://memeburn.com/2010/10/local-ngo-nominated-for-prestigious-international-social-media-award/

2 http://shesthegeek.co.za)

3 http://blogs.worldbank.org/category/tags/rlabs