On the basis of case studies in Finland, this paper describes and analyzes how the museum community has designed, integrated and implemented ICT in its organizations. The museum community has participated in the development of a conceptual framework for ICT services as well as the resources required to put them to use. Due to the similarity between this sort of work and the tasks performed at living labs, I believe that museums could benefit from dialoguing with living labs about their methods, networks and new technologies, indeed their entire ecosystems.

Living labs include the public, private and civil sectors as key actors as they generate and test new products and services. They are spaces of innovation that engage these actors at the different phases of development. But most importantly, the use of living labs' user-centered design methods is becoming much more widespread.

Museums create and use products and services to further their mission of conserving, researching and communicating our common cultural heritage. This paper addresses how museums can make use of and benefit from living labs in their attempts to open their institutions to new audiences and enhance audience participation. This paper also discusses how communities can actively participate in the creation of museum programs and activities.

The existing literature (Eriksson, Niitamo, Kulkki & Hribernik, 2006; Eskola, 2011) describes the work carried out at living labs and contrasts it with work done in museums in Helsinki where interactive pieces have been produced and implemented through a co-design process involving external collaborators, audience and museum staff.

My hypothesis is that if cultural institutions like museums, exhibition halls, libraries and cultural centers acted like living labs, or took part in their activities, they could begin a dialogue with other strategic partners, including an array of research units, and the civil and private sectors. Rather than fostering innovation in their own spaces and based on their audiences' needs, museums currently use technological solutions designed for other contexts, adapting theme to fit their needs. By changing the way that museums refer to themselves and their partnerships, it might be possible not only to shed light on possible collaboration strategies but also to review the role of museums in society and the future. Though the term "living lab" might be a fad, in the context of this publication it may help facilitate participation in and collaboration with the museum community. This paper also contrasts museums and living labs to highlight their common interests and possible points of convergence.

As a result of my research, I believe that museums need to renew themselves in order to better incorporate ICTs into their communities with a user-centered design approach. User-centered design (UCD) is an approach and a process that heeds the needs, desires, and limitations of a product or service's end users at each stage of the design process. UCD has been widely applied due to its ability to help people appropriate and incorporate new technologies. UCD is a design philosophy and a process.

The concepts underlying living labs could be useful to the museum community as it attempts to develop research tools that enable active participation in the development of technology and in innovation by means of products and services tailored to their own needs. Museums today are constantly changing and assessing their role in society and, as a result, their possible partnerships. They must take a proactive approach to financial and social challenges, and thus ensure that a museum visit continues to be a favorite outing for youth. If museums begin to consider their audiences as major players in experimentation with products and services, a new generation of tailored solutions for the cultural sector will appear. Once museums become partners with living labs or position themselves in living-lab ecosystems, they will become creative spaces of social and technological innovation.

First, I would like to analyze three projects in museums in Finland in which I have participated. I will then describe projects in which interaction designers have worked with museums to open up the discussion while developing products and services for museums. I will go on to present a description of some of the most important and well-known international museums that have invested in the development of technology adapted to their context. Museums like the Indianapolis Museum of Modern Art, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the San Jose Museum of Technology are exploring social technologies (3D environments, videoblogs, photoblogs, weblogs, microblogs, etc) and developing open-source software. In these cases, designers working in the museums' media teams have taken the initiative in integrating technologies. Such media teams are generally speaking part of the museums' marketing or communication departments, though on occasion--at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, for instance--designers work in conjunction with the education department. Only very seldom is the media team involved in the development of an exhibition from the very beginning. When that does occur, the aim is to understand the possibilities offered by ICT as a way to conceive of a different exhibition or a different relationship with the audience. Likewise, rarely are the design concepts developed within the museum community.

In my previous research in the museum domain (Salgado, 2009), I collaborated with museums and exhibition halls in Helsinki whose staffs did not include interaction or IT designers that could be involved in the conceptualization and implementation of digital services for their specific needs. For these museums, then, the possibility of working with an external partner capable of co-designing tailored digital services was new. In these cases, the projects I worked on not only entailed providing digital services and co-designing implementation with the museum community, but also co-creating a concept geared towards motivating visitors, collaborators and museum personnel to interpret exhibitions. All three of these experiments took place in Helsinki from 2005 to 2008.

This approach to design in the context of museums was the result of understanding not only how technology facilitates these processes but also the concepts and frameworks that ICT is bringing to cultural institutions. The free- or open-source community, for example, has been introducing concepts such as non-market production and peer production (Blenker, 2006, p. 90). To successfully bring these concepts to traditional cultural institutions like museums requires paying attention to exactly how they can be integrated.

In the experimental projects in two museums and one exhibition hall in Helsinki, Finland I was part of a team of design-researchers introducing interactive pieces that facilitated and motivated community-created content and sharing. All three projects took place in art and design museums where traditionally the only ones authorized to comment on and interpret the exhibited works are curators. In my interactive pieces, other people in the museum community (museum guards, docents, external collaborators, visitors and cleaning personnel) were able not only to interpret the collection but also to make suggestions on the re-design of software and then to test out those suggestions.

These three projects served to create a concept and to develop strategies for its implementation in the context of museums. They are presented in chronological order. The analysis of the findings in each of them was used to give shape to the next project. In these cases, the back-and-forth between making and reflecting on what had been made enabled the development of the central concept: designing museum-community participation through the interpretation of art and design work.

These three cases demonstrate how institutions can benefit if they encourage and guide the production of community-created content in order to bring new interpretations to their collections. In this paper, the term "museum community" refers to the staff working in the museum; external collaborators contributing to the museum, and the audience. These actors constitute a community insofar as they have common interests regarding the content of the museum and relate to a common space and way to explore that space. Moreover, as creators of content they also envision a common goal: to contribute to the museum experience by adding their own insights.

In working on these interactive pieces in different museums, the need to integrate ICT and its concepts and frameworks into the daily practices of the museum became clear. Peer production of content, which was central to these cases, proved a way to genuinely democratize the content of the exhibition and its interpretation. At the moment, however, art and design work at museums is interpreted mainly by curators and experts.

2.1 Sound Trace in Ateneum Museum (2005-2006)

This project took place at the Ateneum Museum, which is part of the Finnish National Gallery. The aim was to design a participative audio tour and a website for the visually impaired and their community. The development team1 gathered and shared digital comments--"sound traces"--online and onsite that discussed the pieces in the permanent exhibition as well as how to navigate the physical premises. Our aim was for the website to contain all existing information on the services Finnish museums offer the visually impaired, as well as audio traces on the exhibition that had been left at the museum by the visually impaired (Salgado, 2009).

Sound Trace attempted to provide greater access to Finnish museums and to enhance the visit experience. It also attempted to create a platform for collaborative sound gathering. Visitors and pieces in the exhibition were to open up a pre-existing,2 dialogue by making it audible. The Sound Trace project demonstrated both the challenges and benefits yielded by audio content produced by the entire museum community; it also shed light on new possibilities for the visually impaired community.

The concept behind the service was developed in conjunction with visually impaired people at a series of workshops and meetings. We also designed a prototype for a texture-touchable screen for a PDA (Portable Digital Assistant), a logo, and the layout for the website. We tested the prototype on the museum premises with various encounters with visually impaired people.

In the context of art museums overwhelmingly geared towards perception and interpretation, the inclusion of the visually impaired community was particularly significant. Through tactile perception, the visually impaired have another point of view on artwork, and sharing that point of view with sighted people was a way to build a bridge to this marginalized community.

2.2 Conversational Map in Taidehalli (2006)

As part of the Young Art Biennale Exhibition a participative installation called Conversational Map was set up in the main entrance hall of Taidehalli (Kunsthalle exhibition hall in Helsinki, Finland). The aim of the piece was to test how well a participative digital board for comments would function at an art exhibition. In addition, Conversational Map also set out to establish a dialogue between visitors who were not at the exhibition hall at the same time. I tried to collect digital comments about the works or about the exhibition as a whole. A two-dimensional compiled image of the exhibition was used to form a map. Visitors could locate specific parts of the exhibition space and the pieces in it, since their positions were analogous to where they were in the real exhibition space. (Salgado, 2009)

Through Conversational Map, it was also possible to include in the conversation supporting comments with links to external resources in the Internet. Inspired by the software ImaNote (Image Map Annotation Notebook), digital comments took the shape of audiovisual material related to the objects in the exhibition. Developed at the Media Lab (housed at the University of Art and Design at that time and now a part of the Aalto University, Helsinki), the software was used to navigate the map and to annotate the pieces in the exhibition. Due to the nature of this software, visitors' comments, which took the form of text, could also include external links. Although the primary purpose was not to test the software, some initial ideas for a new version of ImaNote came from the observations of how Conversational Map worked in the exhibition hall.

While this interactive piece was up in the exhibition, I collected material on the visitor-created content found on the map and on the notes taken about the conversations in the exhibition venue. This idea of encouraging various members of the museum community to leave their comments in a common interactive piece was re-defined in the next project, The Secret Life of Objects. In this second project, I spent more time attempting to motivate and include more people, such as the museum's designers and guides.

2.3 The Secret Life of Objects in the Design Museum (2008-2009)

The aim of The Secret Life of Objects was to develop services for the permanent exhibition at the Design Museum Helsinki. The people working on the project were from the Media Lab and the Design Museum 3 , as well as an external sound designer (Salgado, 2009).

The goal of my research was to further develop the concept of a participative digital board by co-designing practices and content material with museum staff and visitors. What was admissible as digital content was expanded to include material in the form of image, video, sound and text that came from workshops and events held in the museum. This material was included as links on the map of the exhibition; these links were intended to encourage visitors to make comments on the exhibition.

Visitors could join in conversations that had been started by participants in workshops or other events. I tried to demystify the role of the expert curator by presenting comments made by children and teens. In this project, there was a clear intention to elicit visitors' creativity by showing multimedia artistic comments such as poems, videos, and pieces of music. Furthermore, this project tried to show how, by means of digital technologies, it was possible to use intangible digital cultural heritage (recordings of poetry readings and children's workshops, for instance) to enrich tangible cultural heritage (the design and pieces in the exhibition).

The Secret Life of Objects explored creative uses for the Museum's collection by forging partnerships between artists, on the one hand, and children and teenagers who play music and do creative writing, on the other. As with Conversational Map, the use of a participative board with an exhibition map as an interface that could be navigated with the ImaNote software proved successful.

Participatory design approaches like those described above could be used to involve those who do not currently play a part in the group of decision-makers. Museums need to understand the potential of participatory projects if they want to strengthen the dialogue with their community.

Both the development of new technology and the shift to a collaborative peer-to-peer culture were taken into account in thinking about future designs for the museum. Practices such as tagging, commenting, voting systems, or even bookmarking will likely be a part of the museum-visit experience in the future. These practices serve to open up the visit experience and to provide opportunities for dialogue on the exhibition. However, if one truly wants to forge an open museum in constant dialogue and collaboration with the community, it is necessary to involve all actors in setting the agenda.

Participatory approaches have spearheaded the development of innovative discourse of the sort carried out at living labs. In the following chapters, I present the hypothesis that making museums a part of the living-lab ecosystem is a way to activate the museum community as creators of concepts for exhibition spaces. Museum-community driven innovation could be a way to open a path towards expanding the limits of these lifelong educational spaces.

Our understanding of living labs is riddled with contradictions. Some researchers state clearly that living labs are actual living environments (Oliveira, 2011; Schumacher & Feurstein, 2007; Eriksson, Niitamo, Kulkki & Hribernik, 2006) where users co-create and test new ideas for products and services. This definition is in line with the pioneer MIT living lab created by William Mitchell. In that project, the challenges of living environments and the everyday life of people were understood as a source of new ideas for research (Niitamo & Leminen, 2011). Later researchers have understood the living lab to be a research and development methodology (Feurstein, Hesmer, Hribernik, Thoben & Schumacher, 2008).

Researchers in the areas of Science and Technology Studies, Business Studies, Computer Sciences and Design Research have contributed to a theoretical understanding of living labs. As a research concept, the living lab refers to a process of developing and investigating a common space for creating and testing products and services. Living labs are joint, trans-disciplinary research environments in which stakeholders from both the private and public sectors are involved. The widespread use of the phrase and its evident importance as a research concept in so many fields suggests the need for a common and flexible vocabulary capable of fostering collaborative projects.

Though their strategies and methods may vary, all those involved in living labs understand the key role of users as drivers of and/or participants in the innovation process. Indeed, certain organizations are calling themselves "living labs" to foster a particular understanding of their possible partnerships and their relationships to end users. For example, the Department of Industrial Design at the Technical University of Eindhoven has branded its integration of education and research as a "living (learning) lab." These "living learning labs" attempt to combine several areas of research in a multiple and open system that enhances lifelong and self-directed learning (Hummels, 2010).

The Technical University of Eindhoven is far from the only educational institution to house what it calls a "living lab." Another example is the group of students that run a cafeteria at Laurea University of Applied Sciences in Espoo, Finland. BarLaurea is a learning environment for the service sector which has operated since November 2002. It provides students with the opportunity to study, learn about and develop service processes. The environment and approach of BarLaurea contribute to the daily studies of the students who work there and participate in all the project's processes. (BarLaurea, 2011)

Sami Isomäki and Hanna Haapanen (2009) have analyzed the possibilities of using living-labs methods for libraries in the context of the Helsinki Living Lab. Though they do not suggest using the term "living lab" to refer to all libraries, they do recommend the living-lab framework as a way to introduce possible future actions in libraries.

These examples provide an understanding of the limits of living labs. Can any organization that includes its end users in the design processes and develops ideas in collaboration with the private sector be called a "living lab"? In my view, the notion of the living lab can be used to help organizations analyze their possible collaboration with end users, developers and funding bodies. What is the benefit of understanding different organizations as "living labs"? It is a trendy concept that serves to help obtain research and development funding. In some countries, supporting living labs is even part of the national agenda (see, for example, Eskola, 2011 in Finland). But living labs are not only about fundraising; they are also about how to turn end users into decision makers in organizations. Living labs could provide key actors in organizations with research methodologies and concrete tools that enable them to incorporate end users in their daily practices and design processes.

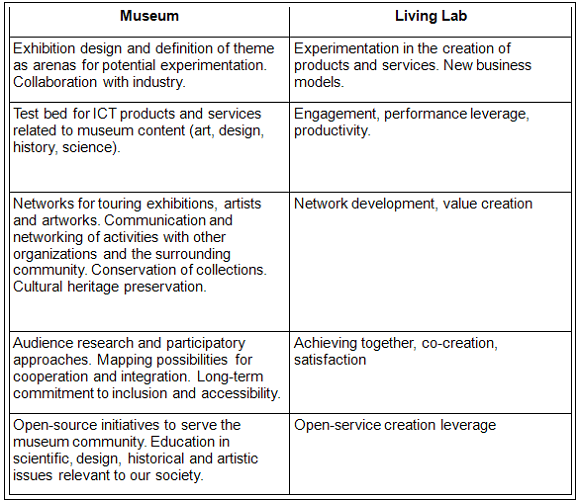

In section two, I used case studies to describe how certain museums have been implementing participatory approaches and methods to engage visitors. In the previous section, I provided the definitions of living labs, and then offered an overview of the organizations that have decided to apply that term to themselves. In this section, I will explain how museums and living labs share not only methods, but also sustaining values. A comparison of the values of living labs and museums demonstrates how they are related and how much they have in common.

The goal of a museum is to acquire, conserve, investigate, communicate and exhibit the tangible and intangible components of humanity's cultural heritage for purposes of education, study and enjoyment (ICOM, 2007). The goal of living labs, on the other hand, is to provide an arena of experimentation where products and services are co-created by civil, private and public sectors. Museums could be the real-life environments in which the products and services that further their goals are co-created.

The column showing the values of living labs was taken from a presentation by Alvaro De Oliveira (2011), current president of the European Network of Living Labs.

In art and design museums, experimentation is mainly focused on exhibition design or the development of themes for exhibitions in a way that offers a new perspective on the permanent collection. Even though in some cases museum shops make a profit from exhibitions, the display and marketing strategies (even at the shop venue) are not conceived as a whole. In certain cases, visitors are included as co-creators of exhibitions (see, for example, LaBar, 2006), or even as curators. But this is a new trend that goes against standard museum practices.

Museums could act as test beds and spaces for user-driven innovation of services and products. For this to happen, it is necessary to identify and communicate the advantages to the museum community of conceiving products and services on these premises. Experimentation, and even failure, must be permitted in the process of developing designs for the museum context so that the museum community can participate actively in the elaboration of concepts and technology for their own use. Museums should aim to build collaborative networks with other research units and other sectors of society in order to better understand what they have to offer.

The preservation of cultural heritage through its artifacts has been one of the core functions of museums and their collections. Part of their mission is to communicate to and educate society through their collections and experts. To that end, they must always expand their network of collaboration in order to accommodate touring exhibitions, artists and artworks. Living labs have been offering their services mainly to regional networks, though there is ongoing research on how to export their services (for example, Ballad, 2011; Apollon, 2011) and how to integrate them into networks (for example, ENOLL, 2011). Museums can benefit from other established networks, like the ones in which living labs operate.

Historically, museums have engaged their audience in a number of meaningful ways, and audience research has been a core activity even though it is not necessarily related to the museum content, but to the provision of services, for example. Not until recent years have experimental proposals attempted to include museum visitors as content creators. Museums have also been increasingly committed to inclusion and accessibility in relation to both their physical premises and their content materials, such as brochures and websites. Many publications and events evidence this concern (for example, the International Journal of the Inclusive Museum, 2008 and the Inclusive Museum Conference).

A number of museums have engaged in open-source initiatives. One example is the Artbabble project (2011), developed by the Indianapolis Museum of Modern Art and currently used by over 35 museums. It is intended to showcase video art content in high quality format from a variety of sources and perspectives. The creation of services, like ArtBabble, which can educate about scientific, historical or artistic issues relevant to our society, is a pivotal concern of museums and their programs. Furthermore, collaboration with other partners (for instance, living labs) that provide services that support or enrich museums' educational endeavors can benefit all participants (users, developers and other stakeholders).

In synthesis, the chart shows how museums and living labs have traditionally used different vocabularies to address similar issues. Indeed, living labs and museums share many core values. Changing the terms in which museums speak of their own research and development might enable them to become key players in the future ecosystems of living labs.

Living labs are collaborative networks based on the understanding that users must be included in research and development processes. Living labs are the result of collaboration between public, private and third-sector organizations. Indeed, the strength of living labs resides in the intersection of people, areas of expertise and value creation. The varying roles that specific organizations occupy in living-lab ecosystems include: enabler, end user, beneficiary, and developer. According to Minna Fred, Mika Kortelainen and Seppo Leminen (2011), who identified and described these different roles, the most successful living lab experiences are the ones that are started and continued by the beneficiaries of the living labs.

Even though the work of living labs sometimes benefit private companies more than communities (Kommonen and Botero, 2012), they have contributed to spreading the word about the importance of users in innovation processes. Experts and museum curators must understand the methods and research tools used by living labs in order to better include their whole community--visitors, external collaborators and all the members of the staff--in the decision-making processes.

As early as 2006, Lizzie Muller and Ernest Edmonds opened Beta_space in Powerhouse Museum in Australia to explore the idea of the exhibition as a public laboratory for interactive art. Beta_space is an iterative approach to creating and displaying interactive art that aims to break down the boundaries between art, science, and technology.

Museums are centers of innovation that, in some cases, have a user-centered approach to design. But this is not enough. If the mission of museums includes communicating and conveying knowledge to the communities to which they belong, they must identify ways and models for doing so. Living labs, which work to enhance partnerships with a range of research units, companies and citizens' organizations, could facilitate this transfer of knowledge.

Most museums concentrate on a certain age group that they have traditionally served and, hence, are familiar with. However, not reaching younger generations especially in art museums might be a problem in the long run. Innovation must be nurtured in every organization. Reaching new audiences might be a starting point for new dialogues and ideas.

Many science centers call themselves "living labs." Traditionally, science centers have been pioneers in making their facilities available for experimental work and in testing different kind of displays and interactive systems. Art, design and history museums can also be places of experimentation, with the risk of failure that that implies, and, in the process, renew engagement with their audience.

The three case studies presented here evidence the possibilities for innovation once a museum community takes part in the design process. Innovative ideas can come into being when the audience and non-curatorial members of the staff are allowed to participate in the creation and testing of concepts for the museum. In the case studies presented, the museum community is a key collaborator in the development of a concept and the shaping of software for its specific needs. As a design-researcher aware of the possibilities offered by Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and the ideas of the community working with them, I was offering tools for co-creating services in the museum context.

Many organizations seem to call themselves "living labs," "city labs," or "centers of creation and experimentation with ICT from a human-centered design perspective." The need to create these new living-lab-type platforms for collaboration is due to the fact that we have not updated and reinforced traditional centers of collaboration, like museums. Combining what cultural institutions like museums have to offer with the services proposed by living labs might get new people involved in said cultural institutions and give rise to innovative ideas.

At the same time, museums must open their spectrum of influence to become centers for innovation and experimentation. New spaces for innovation are necessary as they involve resources and participants other than those associated with established institutions. Old spaces must also engage in innovation in order to incorporate ICT with a user-centered design approach as smoothly as possible. Living labs could be a research tool capable of providing the museum community with the means to actively participate in the development of technology for their own needs. It is necessary to appropriate the vocabulary of other sectors of society, like "living labs," in order to motivate collaboration and plan future strategies jointly.

Communities at cultural institutions (personnel, visitors and external collaborators) do not tend to be technology-oriented, so it is important to take advantage of opportunities to facilitate the appropriation of ICT (including social media and digital services). This appropriation happens slowly and not without tensions and negotiation. Living labs offer methods and tools for aiding end users as they appropriate ICTs.

Museums today could take the initiative in fostering participation in living labs and their ecosystems; they could take on different roles (users, developers, researchers, enabler, etc) or make their own physical spaces and audience available to co-create products and services that make use of living-labs methodologies. Other cultural and educational institutions, such as the universities of applied sciences in Finland (Neloskierre, 2011), have already defined their roles in living-lab ecosystems. Museums, though, are still not part of this equation. Museums must begin to act like laboratories, that is, sites for experimentation. To this end, museums might begin to call themselves "living labs" and to participate in living-lab-type work. If museums positioned themselves as sites of experimentation within living-lab ecosystems, they could better achieve their mission. Otherwise, museums will continue to serve an aging population and fail to engage the concerns of current society. Only by listening and trusting the community is it possible to understand the movement of our society towards openness, collaboration and sharing. Living labs could provide methodologies, tools and networks that help achieve these goals. Living labs could also benefit from collaboration with museums because of their well-established reputation as trusted and knowledgeable institutions with a clear focus on cultural heritage. Museums are a stimulating environment for creativity and innovation, and they should take part in living-lab ecosystems.

1 Mariana Salgado, Anna Salmi, Arto Kellokoski and Timo Londen

2 It is a pre-existing dialogue because visitors and museum pieces are in a constant dialogue, even before the interactive pieces appear.

3 The direct participants in the project were: Svinhufvud, Leena; Botero, Andrea; Krafft, Mirjam; Kapanen, Hanna; DeSousa, Diana; Eerola, Elina; Louhelainen, Anne; Vakkari, Susanna and me. External experts that worked with us: Atte Timonen, Lily Díaz, Jukka Savolainen, Marianne Aav, Tommi Jauhiainen. Other collaborators were the teachers of the groups that participated in the workshops: Rody Van Gemert, Nana Smulovitz-Mulyana, Outi Maria Takkinen and Onnela Päiväkoti.