Developing decentralised health information systems in developing countries -cases from Sierra Leone and Kenya

Introduction

The vast majority of communities in Africa, and in the developing world more generally, are plagued by poor health services and poor health status. Global efforts to improve this situation have recently gained momentum as part of the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDG) project, where three of the eight MDGs, MDGs 4 and 5 (reduce child and maternal mortality) and 6 (combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other killer diseases), are health related. The MDGs are addressing the need for changes and improvements at the community level and can only be achieved through active community participation. Framed within the global efforts to improve health in poor communities, this article address the issue of community participation through strategies to engage the community level in the design and development of Health Information Systems (HIS). Without reliable information on current situation and trends in health status, it is not really possible to improve the situation, as one would not even know whether the MDGs are achieved or not. With only few years left until the 2015 deadline to achieve the MDGs, global agencies such as the WHO are giving considerable attention to efforts to develop efficient HIS to measure progress made towards achieving the health-related MDGs (see for example WHO 2011). In this article we present a case study on the development of the HIS in Sierra Leone, a project initiated and initially funded by the WHO/Health Metrics Network as a pilot for how a Least Developed Country could take advantage of modern ICT and develop their HIS despite very poor infrastructure.

Illustrated by a case study from Sierra Leone, this article addresses the issue of strategies for developing decentralised bottom-up HIS in developing countries more generally, and for the development of community based HISs aiming at empowering local communities and their structures in particular. The project was following a community based participatory approach which we term 'cultivation' (Braa, Sahay, 2012) in contrast to 'construction'. Cultivation denotes a way of shaping technology that is fundamentally different from rational planning and engineering methods as it is based on the resources present in the local social system. Given the provision of technology components such as software, hardware and standards, the overall information system is regarded as something that grows into place, based on the potential in what is already present in the community. This community based approach is strongly linked to the central role given to community participation in the WHO's Primary Health Care (PHC) approach (WHO, 1978), which requires and promotes maximum community trust in the system and participation in developing and running the health services.

In terms of information systems and technology, the project has applied a strategy of integrating various smaller subsystems into a data warehouse. The resulting integrated data warehouse includes information of different types, such as data on health services, health statuses and demographic surveys needed to address equity in health services provision and health status and thereby the needs of disadvantaged communities. Important in this context is that striving for equity between poor and rich geographical areas and population groups will require an HIS that, for core components, is shared across a country, state or region to measure and monitor the extent to which equity is being achieved and to pinpoint areas where more resources and efforts are needed. Thus, for an HIS to best address the needs of local communities, it will need to be an integrated part of a larger area HIS framework.

This paradox, that locally based HISs that are addressing the needs of communities need to be part of something bigger in order to be useful, will be described and discussed in this paper using the case study from Sierra Leone. Important in this context is that Sierra Leone is a small West African country ravaged by a civil war in late 1990s. It is one of the poorest countries in the world and was ranked 180th out off 182 in UNDP Human Development Index report in 2009 (UNDP 2009). In order to complement the case study from Sierra Leone, where the infrastructure is still poor, with cutting edge infrastructure development currently being established in some parts of Africa, we give a brief description of an HIS implementation in Kenya, which is similar in content and aim but different in the infrastructure used. In Kenya the system is implemented using one central server and "cloud infrastructure" using Internet over the mobile network. While in Sierra Leone the traditional Chiefdom structure is using the HIS to address equity and document their demands for improved health services, in Kenya the significant issue is that improved Internet and mobile telephone infrastructure is enabling the community level to get access to their own information and to analyse and to disseminate it within a larger framework, and thereby, potentially, to be better able to address their demands.

The research presented in this article has been part of the Health Information Systems Program (HISP) research network, which started in South Africa in the 90's and has since then been engaged in action research, participatory design and open source software development in a number of developing countries (Braa et al. 2007). The development and application of the free and open source software called District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2) as a joint collaborative effort across countries and institutions have been an important part of the research in the HISP network. Development in both Sierra Leone and Kenya is based on the DHIS2.

This article will proceed as follows; the next section will provide some background on related research, then we will present the methods applied, before describing the case of Sierra Leone. Thereafter, the case and its implications are discussed using "snippets" from the Kenya case before the conclusion is finally reached.

Background

Trends in global health and the HISP project

The recent years have seen an increasing focus on HIS as important for effective and efficient health systems, especially in developing countries. The international community has also emphasized the need for better HIS to track the MDGs, and several initiatives have been set up to tackle the challenge. In 2005, the Health Metrics Network was created as "the first global partnership dedicated to strengthening national health information systems" (HMN 2005). At the same time, many of the challenges countries face with their HIS come from fragmented systems propagated by the diverse international organizations supporting them, leading HMN to become a strong advocate for the building of national HIS integrating data from the various health services and health programs as well as from various donor initiatives. Following the HMN initiative, many developing countries are in the process of strengthening and revamping their national HIS. On the ground, however, HIS development in developing countries has proved difficult due to organisational complexity, fragmented and uncoordinated organizational structures due to similarly uncoordinated donor initiatives all maintaining their own HIS (Braa et al. 2007), unrealistic ambitions leading to a "design-reality gap" (Heeks 2002), and more generally, due to the problem of sustainability (Kimaro and Nhampossa 2005, Sahay et al. 2000).

National HIS are including aggregate statistical data of various types from health services and the population served by these services. The primary aim of these information systems has, until recently, been to provide health management and service providers at all levels of the health services with timely and accurate data, based on which, for instance, resources can be allocated and epidemics can be monitored. As part of the HMN approach (HMN 2008), however, dissemination of information to community and political structures, media and the general public has been advocated as an equally important objective for national HIS, as a way to promote health advocacy, transparency, democracy and good governance. Following this, the HMN recommends countries to include free access to health information in their national legislation.

Communities, widely speaking, will have their interest linked to this latter outwards reaching aspects of the HIS. In this perspective, organized community structures will use information from HIS in their efforts to improve health services and for development of their communities more generally. The community is generally seen as a key level for social development in developing countries. Such development will rely upon community participation in decision-making for social development at the local level (Midgley 1986). Community based participatory design (Braa, 1996, Byrne, Sahay, 2006) is extending this perspective of social development to the field of information systems and the tradition of participatory design. Community based participatory design in health care in developing countries will most often refer to the design of systems for community health workers, or systems to support various outreach health services in the communities. In this article, however, we will use the term community participatory design in a much broader sense to address the design and development of systems aiming to serve and support the whole community, the organised community structures as well as the general population in the community. Furthermore, these systems are also addressing the needs of the health workers working in and for the community. In this way our perspective on community informatics is in line with de Moor and De Cindio (2007), who are arguing that the requirements for such systems are fuzzy and, as with the supporting ICT, in a constant state of flux.

The case studies from Sierra Leone and Kenya presented in this article are both reporting from development of HIS and software carried out within the HISP network. HISP started in three pilot districts in Cape Town at the advent of democracy in South Africa in 1994/95, as part of the new government's reconstruction and development program. Equity in service delivery and uplifting of those who had suffered during Apartheid, and the creation of a decentralised health system based on districts, were key objectives in the reform process. The role of HISP in this period was to identify information needs and to engage the community of end users and local management structures in the process of developing new health information systems supporting the decentralisation (see Braa, Hedberg, 2002, Braa et al. 2004).

It is important to note that the original key members of the HISP team in South Africa had background as social/political activists in the antiapartheid struggle and other social movements, or they had background from the Scandinavian participatory tradition. As a consequence of the background of the team members and the political context of South Africa during these formative years, HISP activists have always explicitly and implicitly seen themselves as political actors in a larger development process.

HISP, participatory design and the community based cultivation approach

The HISP participatory approach to action research and information systems design was initially influenced by the so-called Scandinavian tradition: a number of union-based action research projects carried out in Scandinavia during the 1970s and 1980s. The focus in the earlier participatory design projects was on empowering workers, who were affected or threatened by new technology, by exploring ways in which their influence over technological solutions could be ensured (Sandberg, 1979; Bjerknes et al., 1987). Later projects focused on more instrumental design issues and shifted toward producing technological alternatives by involving workers in cooperative design at the workplace (Greenbaum & Kyng, 1991). Adaptation of information systems to the local context, local empowerment through participation and practical learning, and the creation of local ownership through participative processes are central issues in the Scandinavian tradition, which, despite the differences in context, have been adapted to the contexts in Africa and Asia through action research in HISP.

The community based participatory approach to the design and development of information systems in developing countries developed within HISP may best be understood through the concept of 'cultivation'.

The concept of cultivation (Braa, Sahay, 2012), in contrast to construction, denotes a way of shaping technology that is fundamentally different from rational planning, engineering methods and the construction of technology. Cultivation is about interfering with, supporting and controlling natural organic processes that are in material; as the seeds sprout, they must be provided with proper cultivation; the soil must be prepared and the saplings cared for and nourished. The term cultivation covers these processes, and in our case, adapting the principles, tools and basic set-ups of the health information system, and then helps them grow into place within the local social system of work practices, culture and technologies, through processes of learning. The health information system being cultivated in this way may thus be regarded as a socio-technical system, or an organism, with a life of its own, with its ability to learn and grow. The spread of technology is therefore better understood as a process of technology learning, rather than 'technology transfer'. Technology, like institutions, is also shaped through such processes of learning and growing into place. Methodologically, cultivation is characterised by incremental and evolutionary approaches, described in terms of 'piecemeal engineering'.

The DHIS software

The key "organising" element in the HISP network has been the continuous and longitudinal development and application of the open source software platform called DHIS - District Health Information System. The DHIS is a software tool for collection, validation, analysis, and presentation of aggregate statistical data, tailored to support integrated health information management activities, but it can also be adapted to serve other areas. It is designed to serve as a district based country data warehouse to address both local and national needs. DHIS is a generic tool rather than a pre-configured database application, with an open meta-data model and a flexible user interface that allows the user to design the contents of a specific information system without the need for programming. The DHIS is developed to serve as a flexible tool in what is described as a cultivation approach above. The software is flexible and it can be easily tailored to particular needs and requirements.

DHIS development has evolved over two versions. The first - DHIS v1 - was developed since 1997 by HISP in South Africa on MS Access, a platform selected because it was, at that time, a de facto standard in South Africa. The second - DHIS v2 - is a modular web-based software package built with free and open source Java frameworks, continuously developed since 2004 and coordinated by the University of Oslo.

Methodology

This paper primarily describes a case from an ongoing action research project in Sierra Leone that the authors are engaged in. Action research is a form of participative research where the researcher takes part in the change processes in an organization, actively trying to improve some stated problem (Checkland and Holwell 1998; Avison, Lau et al. 1999), in this case, the poor provision of health services throughout Sierra Leone, in particular, at community level. Our research, then, centres on understanding the processes at work, while at the same time using this understanding to improve the current situation.

We are all, to various extents and changing over time, immersed in change-processes and working closely with the owners of the problems we try to solve. As such, we are involved in open-ended and continuous phases of design, development, implementation, and evaluation of interventions, with a stated aim at improving some given subject, as according to principles of action research (Susman and Evered, 1978). The authors of this paper have thus participated in most of the events described in the case description later.

Three of the authors have been involved in the project in Sierra Leone on an on-and-off basis, spending considerable time in the country through many visits of up to 2 months. The fourth author is a formal employee of the project and a national of Sierra Leone, working in the Ministry of Health there for the last 4 years. The fifth author is working in the Ministry of Health in Kenya and played a leading role in the project in Kenya, where also the third author participated.

The project started in 2006, with the authors given a mandate to improve data management through the establishment of an integrated data warehouse and build institutional capacity for data analysis. The background for this was a situation of fragmented data streams, duplication of data collection, and little use of information from community to national levels. The research approach was thus solution-oriented, without a clear formulation of hypothesis beforehand. Rather, the research part of the project was focused on the interaction between technology, organization, and community through a participative cultivation approach in reaching the above mandate. Over several engagements, research questions were formulated to help with the various practical challenges that would emerge. Central to these were the following two interrelated challenges, 1) to cultivate the system at local level in order to become relevant and useful to the local community, and 2) 'scaling' the system to multiple communities in order to ensure that local decision makers had access to not only their own, but data from across the country to allow for comparison and evaluation. Within the larger combined research area, local cultivation and scaling, research questions were open-ended and dynamic.

Over these years, all authors, apart from our co-author from the Ministry of Health in Kenya, have been repeatedly travelling through Sierra Leone, engaging in participatory design of software and data reporting forms, and training in the use of these. Furthermore, we have been actively engaged in promoting information use at all levels through preparing for and participating in review meetings.

The primary mode of engagement has been capacity building, at all levels. This has taken place not only as formal training workshops, but also as on-site training at district levels and in relation to national and district review meetings. These training sessions have all been used in the development process to include the users by getting feedback and inputs from them on how the system could be made more appropriate and relevant for them. Training has also been used to foster a culture of information use by discussing how districts could engage with their communities to improve health services. Thus it is fair to say that a clear-cut division between training and participative development, and research for that sake, did not exist.

In 2008, a three-week training for national and district staff was carried out, focusing on computer use (a large proportion was computer illiterate at the time), using the data warehouse application, and analysing data from an epidemiological point of view. All districts have later been given additional on-site training during their day-to-day work. Refresher trainings have been held when district supervisors were visiting the districts, and also as joint workshops for all districts. Training has also been an arena to engage with other actors; a workshop was held for representatives from international NGOs to look at their information needs and how they could get this information from the new system. All trainings were semi-structured, trying to promote informal discussions with the participants.

In addition, more quantitative research methods were employed, especially in relation to data analysis. Health data would be processed and analyzed to prepare for review meetings, both in relation to actual use of the data for health management, and for assessing data quality and areas of potential redesign of the reporting forms. For this we used two key data collection forms, for which we had data from most of the country's around 1000 health clinics. Data since 2008 were included in this work.

Kenya represents another action research project that is related to Sierra Leone in terms of technology, goals, strategy, and people involved. The same methodology has been applied in Kenya though the Sierra Leone involvement spanned more than 4 years compared to the about one and a half year research and implementation that took place in Kenya.

Community participation: the case of HIS development and use in Sierra Leone

This paper builds on events related to reforming the health information systems in Sierra Leone in the period 2006-2011; a process that is still ongoing. Sierra Leone is a small country in West Africa, with approximately 5 million inhabitants, and has, as recently as 2001, come out of a decade-long civil war. Picture 1 shows the innovative data collection tool for illiterate community health assistants, representing both the sorry state of the country and how this is often solved locally in communities. With this background, many international organizations have been present in the rebuilding efforts, and in 2006 Sierra Leone was selected along with a few other countries to be a "wave one" country by the Health Metrics Network (HMN), a Geneva-based partnership with the World Health Organization (WHO). This spurred the events described in this document, of which there have been many participants, from the local clinics and district health offices, to national authorities, NGOs and donors in-country, international organizations like WHO and HMN, universities, and other regional actors like the West African Health Organization.

Summary of events

The case is a longitudinal action research project spanning many years, and a full description of the process is beyond the scope of this paper, though a short summary is useful to put the discussion in context. First, from 2007, the HMN-led project focused on introducing software to handle aggregate health information from health facilities, with two early goals: geographical coverage of all 13 districts in the country, and content coverage by including as many monthly reporting forms in the software as possible. For this the HISP group was engaged for implementing a data warehouse, using the DHIS2 software, and build capacity related to this at national and district level. The first two years were thus about piloting and rolling out this software, with the majority of effort going into capacity building. Once geographical coverage had been achieved, the utility of the data increased, and expansion in this phase (2009-10) shifted towards creating the demand for the information, including capacity building at national level and for NGOs, as well as development of information products and active dissemination of both these and the processes behind making them. It was in this phase that information use at the community level became a priority, which will be described below.

System development

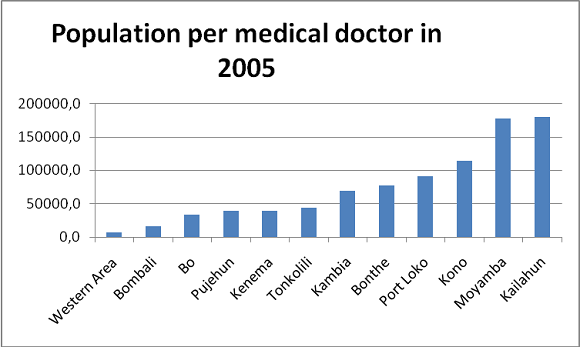

System development In order to design or customize DHIS2 as an integrated data warehouse (IDW) that fit Sierra Leone, a technical team was established. The team was composed of HISP members, Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) officers at national level and district levels, M&E officers from health programs, IT technicians, public health officers, and health workers. However, prior to the technical team creation, DHIS2 experts from HISP had created a prototype of the IDW showing how different data sources can be integrated together and enable a cross data analysis that would generate more meaningful information. The prototype contained the hierarchy of organisational units as given by the MoH: National level ? districts ? local councils ? health facilities. This geographical and hierarchical representation of the HIS matches with the MoH structures and channels of data reporting and use. In addition to this hierarchy, data from three different sources were integrated: namely population data, Extended Program for Immunization (EPI) and human resource data. Data available from 2005 was imported by district into the system for three reasons: show how data from different sources could be integrated, have data to perform training of the software with, and to give a base for comparing newly entered data. At that time, the system was able to generate automatically health worker distribution per population and per district. It was the first time such a graph was available from one system in Sierra Leone. This is shown in Figure 1 below. The prototype was purposefully designed to help stakeholders at different levels understand what an IDW is and thus enable their active participation. Having seen the potentials of this solution, the first concern of districts M&E officers was to be able to generate health information out of the system by chiefdom, local councils and health facilities. While generating health information and feedback reports by health facilities is obvious because data is captured by health facilities, there emerged a challenge to represent another sub-district level, the chiefdom. If health facilities can fit into chiefdoms and local councils, the hierarchical relationship between local councils and chiefdoms is not one "parent" to one or many "children". Local councils are hierarchically above chiefdoms but one chiefdom can belong to two local councils. The representation of such complex hierarchical relationship is not straightforward in the DHIS2 hierarchy logic. However, the participation of district M&E officers helped us understand their needs better and we used alternative hierarchies in DHIS2 to represent both local councils and chiefdoms. Through this participatory process we gradually integrated different data sources - HIV/AIDS, reproductive health, maternal and child health etc - and defined required indicators as well as feedback reports that would be used at different levels of the health system. Awareness meetings with local councils and other local stakeholders were conducted as part of this process.

The initial customization described above took place within a training framework so that the core national team was trained to learn the software which enabled them to participate in the customization. Training of the larger group of users, district information officers, health program M&E officers, and the like, was then initiated and has been a core focus for the project.

While the software DHIS2 was the natural subject of training, it was also a platform to cover issues such as data quality, analysis, and general epidemiology to decide what kind of data was important and what kind of information products should be created. From the onset of the project, a three-week intensive course was held for all district M&E officers, with the aim of preparing them as independent teams for districts, able to work closely with communities and civil society in processing and disseminating relevant data. This was also used to foster local participation, as the training was used to discuss information needs, problems with data quality, and how they saw the new system as being representative of their needs. The developers of the software participated at this training, and discussions about functionality with district staff provided important input to the development process. Many new functionalities in DHIS2, for instance reporting on data completeness, originated from this training.

A second phase of training took place at the local level around the country. In relation to installation of hardware and software in the districts, training was given on-site to M&E officers, and supervisory visits that were carried out regularly also included re-training. In these sessions, the core team would sit with only 2-3 people, focusing on the information cycle from collecting data (at facilities and district offices), processing it (in relation to planned monthly review meetings), presenting and analyzing it and making action plans (at the review meetings with participation from facilities and civil society).

Infrastructure and HIS architecture

The civil war that ended in 2002 had destroyed many infrastructures and when full-scale implementation started in 2008, roads, power supply, and internet availability were still major problems. Internet availability was very limited both in the capital and in the upcountry. The main source of power supply was generators, and getting power from the national grid was incidental. These settings made running a computerized information system very challenging. In addition to these infrastructural challenges, lessons learned from the implementation of software in 2007 showed that keeping the computers virus free and up and running was not trivial. The lack of connectivity made it difficult to update antivirus software in the districts, and consequently the entire MS Access based database was often corrupted or destroyed by viruses. Moreover, when district health offices called local IT service providers for troubleshooting, the solution they often offered was to format the computer without regard to the existing data.

Being mindful of the issues mentioned above, and keeping in mind that DHIS2 is a web based system, a decision was made to go for a replication of instances of the system in every district. In each district a local server, one client computer and a local area network were thus deployed. Both the local server and the client computer were low power based and able to run on car battery that can be charged with solar panel or a generator - when there is fuel to run it. The operating system (OS) adopted was Ubuntu Linux to make sure that they will be less sensitive to virus and thus not rely on inadequate local IT support service. However, existing computers running MS Windows OS were also included in the network as clients. So while the local server is Linux based and runs DHIS2, client computers in the local network area can access the same system and work collaboratively on the same database even if they have different operating systems. This networking aspect of the settings was quite useful for district people because they could now work from different computers on the same database. At the national level DHIS2 was also installed on a server running the same Ubuntu Linux OS. A local area network was also set up within the MoH to enable access to DHIS2 within the MoH.

At the end of every month, district M&E officers are supposed to capture data coming from health facilities within their district, generate an export file from DHIS2 and send it to the national level. The export file is sent via email when internet is available or very often in person on a USB pen drive. At the national level the administrator of the system collect the district export files and import them into the national instance of DHIS2.

On the one hand, although this organization and these procedures look more appropriate to the context, it was very challenging to maintain and keep updated all the local instances of DHIS2. For instance, any changes to the metadata in the national database have to be replicated in all other instances to keep them compatible. Obviously this requires travelling to all the 13 districts on poor roads.

On the other hand the low power computers were not very strong and parts had to be changed because of various failures in the warm, humid, and dusty environment. Fortunately, as the government was investing in infrastructure, power supply improved and the system moved gradually from low power computers to regular ones. However, despite the progress in road construction and power supply, internet availability and reliability is still weak and hampering the shift from distributed instances to one central server.

Information use

As the use of the new data warehouse was maturing, work began to start utilizing the data it produced. This is, of course, the reason for the introduction of the system in the first place, but it is also a strategy to improve data quality, as only by use and self-interest in the data the quality would come under scrutiny and new solutions be proposed. The project thus initiated the use of quarterly bulletins, a modest 4-page leaflet comparing all districts on a handful of health indicators, as well as some indicators on data quality. The first bulletin was released in May 2009 and disseminated widely, including all districts and members of a group of international health partners (WHO, World Bank, DFID, etc.).

The bulletin contained charts derived from DHIS2, ranking the districts from worst to best performers. Picture 2 shows the front page of one bulletin. While the data was of dubious quality, based on partly incomplete data, the effect was at least to start discussions about how to improve it. Shortly after, data reporting increased significantly, so that the next bulletin had more complete data.

In addition to the bulletin, a league table was developed, in which a few key indicators were used to give each district an overall score, ranking them based on data quality, institutional delivery rate, immunization rate, antenatal care coverage and the like. This league table was presented at the annual review meeting at the Ministry of Health, with participants from all districts. The league table raised much discussion especially in relation to a few indicators that had much variation among the districts. One such example is institutional delivery rate, an indicator directly linked to the Millenium Development Goals about maternal and child health.'

The development of the bulletin and league tables were initiated at the national level. The selection of indicators to include was based on relation to the MDGs, and data quality, such as institutional delivery rate (linked to infant and maternal health), and reporting rates of the main data collection forms that contained this data. Since the data completeness was an issue, only indicators for which there would be adequate data available were included.

In 2009 Western Area (mostly consisting of the capital Freetown) was one of the districts scoring very low in term of institutional deliveries. Being very concerned by the poor performance of his district, the District Medical Officer (DMO) in Western Area decided on two strategies to improve. First, to collaborate with private facilities (of which the district has many more than rural districts) to get their data on institutional deliveries, and second, to release a note in the newspaper informing the public that maternal and child health care was now to be free of charge in Western Area district. As shown in the Figure 2 below, institutional deliveries have increased steadily in the district. The free maternal health care policy could not alone explain this increase, the involvement of private facilities has to be taken into account, but in any case the results are remarkable and were soon distributed globally by the Health Metrics Network as a strong case for investing in health information systems. The new figures in turn help them plan well and advocate for adequate resources for the district.

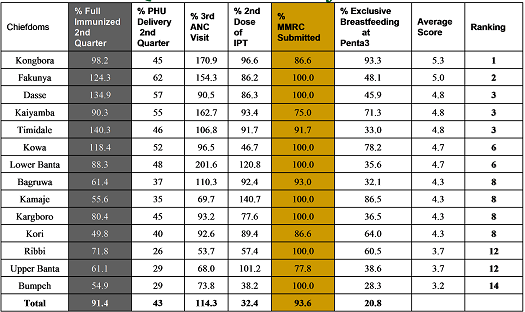

Districts also have their monthly review meetings, and following the example of the bulletin and league tables, several districts started to make chiefdom league table, ranking the sub-districts (chiefdoms) in a similar way. These review meetings are attended by all district stakeholders such as health partners, community counsellors, health providers, traditional and religious leaders, etc., and have led to a plethora of locally driven initiatives on improving service delivery in their respective communities. The development of a district and chiefdom league tables covering important health indicators, the active dissemination of these, and discussions with key stakeholders on how to improve on these indicators form the highlight of such review meetings. For instance, the use of the chiefdom league table showing performances of each chiefdom on key health indicators (such as institutional delivery, fully immunized children, etc.) in Moyamba district has raised a competitive feeling among the local communities. Table 1 shows an example of chiefdom league table.

In this case, Kongbora chiefdom, after coming last in the first quarter review, improved to take the first place in both the second and third quarter reviews. Fakunya Chiefdom was the sixth in the first quarter review, but improved to take second and third places in the second and third quarter reviews. Dasse Chiefdom was eighth in the first review meeting but took third and second places in the second and third quarter reviews. Certificates of this, provided to the paramount chiefs at the review meetings, were brought to local council meetings as proof of good performance, as shown in the Picture 3 below.

By comparing themselves and knowing more about health indicators, local community leaders decided to better organize health service delivery in their community and put more pressure on upper level for more resources and more support. In many communities, local counsellors are now putting in place bye-laws for the Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) to help pregnant women deliver in the health facility where they can have a clean and safe delivery with trained staff in attendance. The District Health Management Team also organized outreach activities eagerly requested by community leaders (Paramount chiefs) after the review meetings to increase the coverage for key health outcomes like childhood immunization. Some communities have also used these meeting to advocate for more resources (human, financial and infrastructure) in order to address the low uptake of services in their catchment areas. In some chiefdoms where institutional delivery rates are low, the paramount chiefs mobilized local resources to build birth waiting homes where pregnant women staying far away from health centres could stay until they delivered.

Involving the communities, including religious leaders, traditional health service suppliers, and the paramount chiefs, the districts are improving the institutional delivery rate, an efficient strategy to reduce infant and maternal mortality. The Moyamba DMO is very proud of the interest expressed by the community members who are now determined to improve service delivery coverage in their communities. "Using the data from the DHIS for the quarterly review meetings, the population better understand the health services performance and are happy and interested to be involved," claimed Dr Kandeh, the Moyamba DMO. "Without their interest, we could not move forward and have high performance". Being able to show improvement in service delivery by using health information at district level, and regularly share it with key stakeholders, led to a major change in prioritizing health services with the community involvement.

The possibility of being part of a larger set of other communities made it easier for local communities to compare themselves with neighbouring communities which in turn triggered the propagation of best practices leading to improvement of health services and high performance. While the data quality shown in table 1 is obviously an issue, as seen from the rather wild percentages for some of the chiefdoms, these problems have triggered a review into denominator data such as population figures which tend to be outdated and not take into account recent migration.

Online web based access in Kenya - Empowering rural communities

Participatory design in the cloud

Sierra Leone is one of the poorest countries in the world and the infrastructure is poorly developed. It has therefore not been possible to implement the DHIS on a central server, which would have been much easier and which is the "industry standard" of doing things in the industrialised world. As the Internet and mobile technology is spreading rapidly in Africa, we include a limited case study from Kenya, where the infrastructure is much better, and probably quite similar to what it will be in most of Africa relatively soon since it is driven by mobile network technology. DHIS2 is currently being rolled out in Kenya based on a central server solution. Initially, the plan was to implement standalone instances in districts around the country, the traditional African way, but during a field visit to Machako in October 2010, a district hospital not far from Nairobi, the course of action was changed. Testing the DHIS2 online server in the information office, everything went well until a power cut left the line dead. As it was a hospital, the generator started and power came back, but the Internet was gone as it would have to be restarted somewhere down the line. The team was just about to conclude that Internet was still not reliable when one of the staff suggested using his "dongle", the modem for the Internet over the mobile network, which, it turned out, worked fine as the mobile networks are not affected by local power cuts. Immediately after this revelation, Internet modems were tested around the country and found to work , and the decision was taken to go for a central server solution, probably the first time for such a country-wide public sector project in Africa. However, the server in the Ministry of Health could not be used as the connectivity was too poor in the building and the server setup not reliable. As a temporary solution therefore, a commercial server was rented through a London based company, meaning cloud computing, although politically it may not be accepted to locate national health data outside the country in the long run. The Coast province was selected as a pilot, and the system was implemented in all districts and hospitals there in January 2011. All users were provided a modem and a budget for airtime. The network was working, but the bandwidth was limited many places, and the cost of the airtime restricted the amount of time online. In order to address a multitude of problems the DHIS2 lab was literally moved to Kenya; the lead developer and others took part in building a local team and engaging in rapid prototyping cycles on site with the users in the Coast province. In fact, "rapid prototyping" changed its meaning; working on an online server meant that the system changed as according to users' input, if possible, on the fly, or overnight.

After the initial pilot and testing in the Coast province, the system was rolled out country-wide during March-September 2011. During a field visit in the western parts of Kenya, in Nyanza and Western provinces, and to remote areas, such as Homa Bay district, where two of the authors participated, the most surprising finding was that the users in districts and health facilities said they had easier access to their own data, as well as data from the rest of the country, than they had had anytime before. The argument was that they could access their data regardless of power-cuts (when they used their laptop), viruses or computer problems, because the data was "up there", always available, "in the Internet". Furthermore, they really appreciated the dynamic updates of data from around the country and the messaging system in the DHIS that was used for communication between users and the system support team to report bugs and to get help when having problems. "Just like Facebook" as one user said.

The new HTML 5 standard has the potential to improve the robustness of Internet and cloud based technologies in Africa, as it allows for offline data entry because browsers implementing this standard are now including a small database. The first version of such a "semi-online" feature was implemented in DHIS late August 2011. The user can now capture data offline by using the memory in the browser and "flush" the data (i.e. transfer to the server) when online. This is a very useful feature in Africa since Internet is not available everywhere and all the time. The following message was posted by a user after the new feature of offline data capture had been included:

2011-09-13 Hi, this is wow! I have realized that I can now work with a lot of easy without any interruptions from network fluctuations since some of us are in the interiors where we have lots of challenges with the network. This is so good, a big Thank you.........

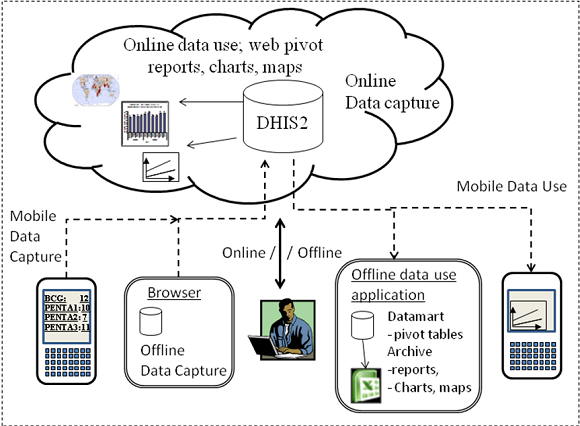

Offline data-use is another important optimization of DHIS2 for low bandwidth in remote areas: the ability to download data for off-line data analysis and use. A small "super lightweight DHIS2" application installed locally is used to download data from a local area and other areas specified by the user, including the indicators and aggregates generated by the system to a data mart, which is then used to generate Excel pivot tables used for data analysis. Reports, charts and maps are generated when "online" and downloaded in PDF format and archived in the offline application. As the Excel pivot tables are not easy to update online regardless of bandwidth, the offline local data mart is actually representing an improvement on some functionalities when compared with the web browsing (see figure 3).

Discussion

- 1. Health information in a community perspective: How communities can use HIS for their own development?

- 2. Design strategies: How to best include communities in participatory design strategies?

- 3. The technology dimension: Is modern Internet technology appropriate at community level in remote areas in developing countries?

- 4. The culture dimension: Are the HIS being developed culturally appropriate at the community level?

Health Information for community development

The case of Sierra Leone is, in the end, about improving health for communities throughout the country. This is done by improving access, quality, and use of health information, both for public health staff and for the communities themselves. The public health system is there to serve community health, so strengthening their capacities to analyze the health situation and make appropriate action plans is in itself a way to use information technologies to improve community health. However, as the case shows, the technology can also be utilized to share data with stakeholders in the communities, such as paramount chiefs, civil society, and NGOs. For example, preparing data from neighbouring districts or chiefdoms, available from an integrated data warehouse, in league tables that are then shared widely with these stakeholders has been a powerful result from several districts in Sierra Leone. While the "owners" of the technology are the organized public health services, the information contained therein is shared beyond the domain of public servants, enabling the communities themselves to shape their response to their health challenges. The information system introduced in Sierra Leone thus contributed both indirectly and directly in enabling communities to improve their situation.

Furthermore, the case shows that the real benefit was linked to evaluating your own situation in comparison with others. In a context where information about your own situation is sparse, and knowledge about what it should be is even sparser, the availability of comparative data from other districts and chiefdoms can at least give a relative performance indicator. The league tables were especially strong carriers not only of information about the community's own situation, but how the community performed compared with others. The maternal and infant mortality rates in Sierra Leone are among the highest in the world, but there are domestic differences that may earlier not have been well acknowledged. Public health service coverage and utilization vary across the country, and by learning from best practises, while fostering some community competition, the league tables enabled the health staff and the communities they are serving to improve piecemeal, striving to achieve small results that have a big impact on the health status. For instance, the example from Western Area, where several measures where tried to improve the institutional delivery rate, was in direct response to the poor standing in the district league table. For this to be possible, the data relating to the community, be it district, chiefdom, or village level, must have something to be compared with. The value of the community data increases manifold when available together with data from other communities. The league tables and health information bulletins served both as carriers of information and in a normative way as guidance relating to what indicators were considered of national importance. Thus, the local levels could both get feedback on how they performed, and knowledge relating to how they were evaluated. The important point here is that isolated information on the individual communities is of less value than the connection to information on other communities. Information technology projects that have a community focus, then, should be wary about the power of transparency and linkages to other communities. While a singular "community system" would provide the community with its own health information, the real benefit comes when comparing one's own information on health status and available health services with information from other communities.

Communities' use of information to promote their own development, as illustrated by the case of Sierra Leone, is providing concrete experiences on how the WHO Primary Health Care approach may be achieved. Community participation in the development of the health services is highlighted in the following way in the Primary Health Care (PHC) concept Article VII, paragraph 4 and 5 in the Alma Ata declaration:

"Primary Health Care: 5. Requires and promotes maximum community and individual self-reliance and participation in the planning, organisation, operation and control of primary health care, making fullest use of local, national and other available resources; and to this end develops through appropriate education the ability of communities to participate;" (WHO 1978)

We may argue that without access to good information on the performance and availability of the local health services, local health status, and an overview of trends in other communities, "participation in the planning, organisation and control of the primary health care", as stated by the Alma Ata declaration, would not be possible.

Cultivation - Community based participatory design

In this section we will discuss how community participation in the design of information systems may be seen as part of, and incorporated in, the participatory design tradition.

In the last section we saw how community participation was an integral part of the WHO Primary Health Care approach; the community is seen as the key participant in the development of the health services for the community. Here we will look into whether such a strategy may also be applied to the communities participating in the development of the information system, which, again, should be regarded as an important pillar in the development of the health services in the community. Tracing the history of the participatory design tradition, we see that it has its origins in the progressive movements of the 60s and 70s, in ways somehow similar to the origin of the PHC movement. Participation for empowerment and social development were the slogans for both movements.

There are however some significant differences between the participatory design (PD) tradition as it has evolved over several decades in industrialised countries and the context of community development in Africa. First, while in the PD tradition, the workplace has been targeted as the arena for empowerment and action. In the context of the development of health services and improving health in developing countries, it is the community that is the arena for social and political development. Second, while the PD tradition was born out of a situation in the industrialised world where workers felt threatened by modern technology and feared joblosses, communities in developing countries are threatened by being sidelined by new technologies and being left out from development. This second issue, that is, how communities may be either sidelined or made to master new technologies will be discussed in the next section. Here we discuss the first issue: Focus on the community rather than the workplace.

As underlined by the Alma Ata declaration, the health services are there for the community and the community needs to take part in their development. When developing health information systems at the community level, two levels of users are important: health workers and the community. While the health workers are users of the systems in the traditional sense, as being defined in the PD literature, the community is the users of the health services and, as participants in the development, control and planning for improved health services, users of the information systems with the aims to pursue these goals. We thus need to extend the PD tradition to also include the community. Greenbaum and Madsen (1993) put forward three rationales for using participatory design approaches:

- a pragmatic perspective, a functional way to increase productivity;

- a theoretical perspective, a strategy to overcome the problem of lack of shared understanding between developers and users;

- a political perspective, a democratic strategy to give people the means to influence their own work place.

In addition to the three rationales that they suggested, a community perspective has been proposed as strategy to enhance both the community as well as to prepare technical development that goes beyond mimicking the first world (Braa 1996):

- a community perspective, extending the political perspective and aimed at empowering communities to control and master ICTs to their own advantage by pursuing their own social and political development.

In the Sierra Leone case we have seen that the formal community structures, the chiefdoms, are taking part in the development of the system as part of their strategy to mobilise resources, create awareness and to improve the health services in their own community.

An example from the case shows how the districts and chiefdoms took initiatives to improve the system, for example, by being instrumental in the development of data completeness reports and incorporating them in the league tables which enabled the chiefdoms to control and check their own data; a task the district team did not know how to measure by themselves. Such direct engagements and initiatives have been important in creating a sense of ownership to the system in the community, which again has lead to the development and dissemination of the health bulletins as a means for the formal community structures to communicate with and mobilise the wider community. Such dissemination of information from the HIS is important to develop further, both as a means for public health advocacy and as a vehicle for community participation. These bulletins may be regarded as first steps towards turning the HIS into a true interactive vehicle for wider community participation.

In Kenya, we have seen how direct and immediate access to own data through the Internet over the mobile network even at the most remote village level has created a significant level of local initiatives and participation in the further development of the system. Clearly, having direct access to your own data and being able to analyse and use it without having to rely on 'middle men', has both created a feeling of ownership of the system and commitment to participating in its further development. The development of the system in Kenya has from the start been driven by local initiatives seeking to release the potential on the ground. Even the fact that the system is based on the use of modems to connect tothe Internet over the mobile network, which is the most significant technical feature of the system, was not planned for. The new solution popped up through interaction on the ground, and changed the course of the entire national project. Chatting functionalities enabling users to communicate is another example of unplanned design features developed through interaction on the ground. Cultivation is the term we use to depict such an open user centred design and development strategy where the potential in the context is released through active participation in the design and development process. The cultivation approach has been important in engaging at the community level because it provides a practical way for the community to have real influence and to get results through their participation.

Internet and ICT at the community level: Appropriate technology?

In the 70's and even later, the term appropriate technology was used in development aid circles to denote technology "simple" enough to be used in developing countries - which was a rather patronising attitude. In this section we will revisit the term and see whether "appropriate" can be given a new meaning in the age of the Internet and cloud computing.

When initiating the project in Sierra Leone, sustainability of hardware and software was a major concern. At that time, there were those arguing that computer technology was not appropriate for rural Sierra Leone. An initial survey showed that literally all computers where seriously affected by viruses. In order to address this problem a Linux based infrastructure was implemented in the districts; a computer without screen was used as a dedicated "no touch" Linux server running the DHIS software and accessed through wireless network by various users in the district headquarter by their browsers. This infrastructure turned out to be very successful, and indeed appropriate. Despite limited initial Linux knowledge, the trade-off was a running system without viruses. Early in the process, an additional smart technology was also tried: low powered 12 Volt computers running on batteries and, the plan was, solar power. This experiment, however, turned out to be not so "appropriate"; the low-powered server did not have sufficient capacity and speed, and users were not happy with screens and performance; various other technical problems put that pilot effort to a standstill.

In Sierra Leone, the Internet is not universally available across the country, a situation which is still similar in most parts of Africa. The norm when implementing country HIS in Africa has therefore been, as in Sierra Leone, until today (2011), to capture the data in stand-alone databases implemented in districts, hospitals and health facilities around the country, and to report data electronically by e-mail attachments or physically on a memory stick to the next level. Significant human capacity on databases, data management and system support is needed, in order to manage a national HIS based on numerous standalone database applications with fragile flows of data between them. Problems of data reporting, completeness and the maintenance of numerous standalone applications across the country make it very complicated. Building a web-based data warehouse on a central server, as is the norm in industrialized countries, and even using a cloud infrastructure, is much simpler technically and in terms of human capacity and needed support structures, for hardware, software and data and database management. Ironically, Africa would need more human capacity for support and maintenance when implementing a country HIS than would, say Norway, when implementing a similar system, because in Africa would need to maintain numerous standalone implementations and complicated flows of data, whereas in Norway only one central implementation would have to be maintained. Cloud based infrastructure using a central server with universal access would therefore be a very appropriate infrastructure in Africa. Based on the rapid increase in mobile coverage in Africa, new cables down both the East and the West coasts of Africa, the situation may be about to change.

The semi-online solutions developed in DHIS enabled by the new HTLM 5 standard which allows for offline data storage in the browser, has been successfully implemented in Kenya. This innovative technology is significantly improving the feasibility of web-based computing using another new technology: the cloud based infrastructure, even in rural remote communities in Africa. In Kenya also, mobile telephones are used to interact with the DHIS; data is reported from remote clinics to the DHIS and feedback is sent from DHIS to the mobile. These examples of new and innovative technologies, including the local wireless network running on a dedicated Linux server in the districts in Sierra Leone, are all characterised by 1) being very appropriate for even rural communities in Sierra Leone, and 2) being very modern and even cutting edge. Therefore, the term appropriate technology for developing countries needs to be given a new and different meaning in the age of the Internet and cloud computing; to exaggerate a bit - the more "modern" and "cutting edge", the more appropriate the technology.

How can culturally appropriate systems be developed?

In the section above we concluded that modern Internet technology is appropriate at community level in developing countries. In this section we extend the notion of technology beyond the mere "technical", the artefacts and the "things", and see it as being rooted in knowledge and people through use and innovation (Fagerberg, 1994) in a socio-technical web (Kling, Scacchi 1982). Furthermore, information systems, such as the community based health information systems in Sierra Leone, are best understood as social systems (Braa, Sahay, 2012). Following these perspectives, 'cultivation' is well suited as a metaphor to describe the approach followed to develop relevant and socially and culturally appropriate information systems. The argument is that the particular components of the information system, such as hardware, software and paper-based data collection tools may be planted in a local setting, so that the seeds may be similar and context free, but local growing conditions, such as culture, languages and social conditions, are infinitely variable. The developing plant therefore needs to be tended and nurtured by the local community who will then develop a sense of ownership and commitment towards it. In this way the information system understood as a social socio-technical system will grow into place as an expression of the local culture and language. Cultivation, as an approach to information systems development, relies upon the development of local ownership and commitment. A bottom-up participatory design and development process is therefore crucial in helping to create such ownership.

The Sierra Leone case demonstrates that the community level HIS needs to be part of the larger national system in order to be able to analyse data about the local health situation as compared with national standards areas and the situation in other areas. Only by enabling the community to use the HIS to analyse their own situation within the larger context will it be possible to achieve the objective of the Alma Ata PHC declaration which calls for maximum community participation.

This means that while local empowerment, commitment and bottom-up processes are crucial, there is an equally important need for making national standards part of the community based HIS. When striving for equity between communities and regions in a country, national standards are needed to identify and target areas of need (Braa, Hedberg 2002). This may cause some tension between the local need for flexibility and national need for standards, which may be addressed through a hierarchy of standards where each level in the health system is free to define its own standards and information requirements as long as they adhere to the standards of the level above (ibid.).

Concluding remarks

This paper has looked at how community participation in both the development and use of health information systems has led to a situation where the communities themselves are taking active part in improving their health status. The main contributors to success in this regard have been identified as involving the communities in the development and use of the health information system, sharing data among communities in a transparent and mildly competitive manner, and, as the case from Kenya shows, using a mix of cloud computing and offline support to further facilitate the above points also for communities not regularly connected to the Internet.

It is clear from the case that communities are not just users of the information system, but they are also participating in its development and they are themselves shaping the way information is handled and used at the community level. Conceptualising information systems as social systems, cultivation is used as a metaphor to understand how culturally appropriate information systems may be developed through local commitment and bottom-up participatory processes.

At the technical level, the cases demonstrates that modern ICT and Internet technologies may indeed become appropriate technology even for rural communities in Africa.

The case of Sierra Leone shows that while the HIS needs to be based on local ownership and freedom to define its requirements, the system must also include the national standards in order to be useful in a wider national comparative perspective. This implies that community HIS need to be connected in a larger, national HIS and that routines for feedback and dissemination are in place. Our case shows how communities are leveraging the national integrated data warehouse in Sierra Leone to make local decisions, which would not be possible without the wider system.