Reducing community health inequity: the potential role for mHealth in Papua New Guinea

Dr Belinda Loring, Senior Policy Officer for the Global Action for Health Equity Network (HealthGAEN) and Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University. Email: Belinda.loring@anu.edu.au

Prof Sharon Friel, Professor of Health Equity and an Australian Research Council Future Fellow at the Australian National University, Australia and Chair of HealthGAEN Email: sharon.friel@anu.edu.au

Prof Don Matheson, Professor of Public Health at Massey University, New Zealand. Email: D.P.Matheson@massey.ac.nz

Mr Russell Kitau, Acting Head Division of Public Health, School of Medicine & Health Sciences, University of Papua New Guinea. Email: rkitau@hotmail.com

Dr Isaac Ake, Health Systems Consultant, PNG. Worked for AusAID, PNG Health Department, Sustainable Development Program, WHO and the Asian Development Bank in strengthening health systems. Email: iake@pngenclaves.org.pg

Dr Urarang Kitur, Manager for Performance Monitoring and Research National Department of Health, Papua New Guinea. Email: urarang_kitur@health.gov.pg

Dr Alexander Rosewell, Epidemiologist, Emerging Diseases Surveillance and Response Team with the World Health Organization in Papua New Guinea. Email: rosewella@wpro.who.int

Ms Heather Randall, Regional Director, Austraining International Pty Ltd, Port Moresby. Email: heather.randall@austraining.com.au. Previously Disease Outbreak Surveillance Officer, WHO PNG Office World Health Organization, PNG.

Mr Enoch Posanai, Executive Manager for Public Health, National Department of Health, Papua New Guinea. Email: enoch_posanai@health.gov.pg

Introduction

Papua New Guinea (PNG) faces formidable health challenges. Health spending per capita, which has fallen about 33% since the 1980s, has contributed to widespread decline in the system (Batten, 2009). Key health system indicators are either static or declining (National Department of Health, 2010). In 2010, PNG was ranked 137 out of 169 countries in the Human Development Index (United Nations Development Programme, 2010). PNG is not on track to meet any of the Millennium Development Goals, and progress towards some is deteriorating. The maternal mortality rate doubled between 1996 and 2008 to 733 per 100,000 live births (Papua New Guinea National Statistics Office (PNG NSO), 2009). This is likely due to a combination of inadequate health and social systems and improved data collection. Stratified health data are limited but the available data reveal marked inequities in poverty rates, life expectancy and child malnutrition between provinces (Bauze, Morgan, & Kitau, 2009). Marked inequities also exist within provinces, with major differences in service activity between different districts, and inequities in access between different facilities (Bauze et al., 2009). However, further understanding of health inequities is limited by a lack of reliable information about health needs and limited use of information on system performance. These are critical challenges that mHealth may be able to address in PNG.

Health systems are both determinants of, and solutions to health inequities (Friel et al., 2011; WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). When appropriately designed and managed, health systems can promote health equity. They do this when they specifically address the needs of socially disadvantaged and marginalized populations, including women, and the poor (Gilson, Doherty, Loewenson, & Francis, 2007). Often, despite the best intentions, many health systems generate health inequity and exacerbate social stratification. Inadequate resources for health and declining infrastructure create barriers to access or result in differential experiences and outcomes for certain groups. Information systems are a critical building block of health systems, and underpin the ability of health systems not just to detect, measure and act upon inequalities, but also to evaluate the impact of efforts to intervene and inform necessary adjustments.

In PNG, the health system has deteriorated markedly over the last two decades especially in rural areas where approximately 87% of the population live. In theory, PNG has a good national health policy. However, the full implementation of the policy has failed due to a combination of obstacles including management issues, relationships, financing arrangements, the skills of health practitioners, institutional rules, uncertain funding, deteriorating infrastructure and political instability (Bolger, Mandie-Filer, & Hauck, 2005). Hundreds of rural health facilities have either closed or are not fully functioning.

Access to technology and information is undeniably a key part of an effective health system and a potential determinant of community empowerment and health equity in PNG. New mHealth technologies are rapidly being introduced in PNG with at least four different initiatives in the last year (BJ Loring, Matheson, & Friel, 2011). The World Health Organization and Government of PNG are testing the use of mHealth in disease surveillance, the Papua New Guinea Sustainable Development Program (PNGSDP) is using mHealth for community surveys in the remote Western Province, the Asian Development Bank and National Department of Health are testing the use of mHealth for rural health facility audits and the Clinton Foundation are using mHealth for rapid transfer of laboratory results from HIV testing. At the time of writing, no evaluations were available on any of these new initiatives.

These innovations offer an opportunity to facilitate rapid and large scale improvements in the flow of data in the PNG health system. However, technology and data in isolation are unlikely to lead automatically to positive change (Gurstein, 2003; Loader & Keeble, 2004). An effective information system needs the following steps: 1) data collection, 2) analysis, 3) information generation, 4) use of information in decision making. Like many health information systems, the PNG system mainly focuses on only the first step. Successful and effective implementation of mHealth depends on a wide range of factors (sub-systems) in the broader health system. A way is needed to determine how mHealth combined with all other factors can lead to the overarching objectives of improved community health and health equity.

The aim of this paper is to describe the current situation of rapid expansion of mHealth technology in PNG and consider its role as a possible tool to improve community health equity. Based on a review of the international peer-reviewed and grey literature, and informed by discussions from a key stakeholder workshop held in Port Moresby earlier in 2011, we first provide an overview of the current uses of mHealth in health systems in PNG. The paper then describes the role of mHealth within the broader health system, and discusses issues relating to evaluation of mHealth effectiveness in improving health and health equity and its impact within the broader complex health system. The paper concludes with key issues that should be considered if this technology is to be used, and evaluated, for health equity purposes in PNG.

Communities in Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea is currently home to over 6.9 million people with the population set to double within 30 years (National Statistical Office of Papua New Guinea, 2009). PNG is one of the most ethnically and linguistically diverse countries in the world, with over 800 distinct languages spoken (Bauze et al., 2009). The vast majority (approximately 87%) of the population live in rural areas (Bauze et al., 2009), some of which are very remote. The mainland is dominated by a rugged spinal mountain range, where most of the population live, rising to 5,000 meters above sea level. The remainder of the population is scattered unevenly, over an archipelago of over 600 islands. Approximately 13% of the population live in 73 urban areas, 40 of which have populations of more than 1000 people (Bourke & Harwood, 2009). A further 311 924 (6%) people live in 'rural non-village' settlements including boarding schools, mission stations, sawmills and logging camps (Bourke & Harwood, 2009). The remaining 81% of the population live in rural villages of less than 1000 people.

Much of the population is without access to safe drinking water or adequate sanitation; 60% of the population rely on surface water (river/stream or spring water) and 70% of households use traditional pit latrines (National Statistical Office of Papua New Guinea, 2009). In PNG, 40% of the entire population are less than 16 years of age (National Statistical Office of Papua New Guinea, 2009) and almost 40% of the population aged 5 years or older have either not received any education or not completed grade 1 (National Statistical Office of Papua New Guinea, 2009).

The capital, Port Moresby, is not linked by road to any of the other major towns and many highland villages can only be reached by light aircraft or on foot. Geography and physical access to services are significant barriers to improved health status. In 2000, more than half of the rural population were estimated to live over four hours' travel by foot, vehicle or boat from any type of government service centre (Hanson, Allen, Bourke, & McCarthy, 2001). In the Highlands, rural residents have to walk more than 4 hours, on average, to reach the nearest road (Gibson & Rozelle, 2003). Rates of poverty vary within regions and within provinces (Bauze et al., 2009). An analysis in 2000 classified rural areas according to disadvantage based on five parameters: land potential; agricultural pressure; access to services; income from agriculture; and child malnutrition (Hanson et al., 2001). Of the 4 million people living in rural areas in 2000, approximately 61% were found to be disadvantaged by either one, two or three constraints.

With 20 provinces, 89 districts, 313 local-level governments and 6131 wards, the challenges for policy makers and health service delivery agencies are substantial (The National Research Institute, 2010). Information to inform policy-makers about population needs is poor. In 2005, birth registration coverage was reported to be approximately 3% nationally (Bauze et al., 2009). To meet the needs of these geographically dispersed communities, PNG's health system is based on a network of 2672 aid posts (approximately 30% of which have closed due to lack of staff and supplies), 702 health centres, 18 provincial hospitals, and one national hospital (National Department of Health, 2009).

mHealth - What is it?

mHealth is defined as the use of mobile communications devices, such as mobile phones, for health services and information (Vital Wave Consulting, 2009). A subset of eHealth , mHealth includes the use of a mobile phone's voice and short messaging service (SMS) as well as more complex applications including general packet radio service (GPRS), third and fourth generation mobile telecommunications (3G and 4G systems), global positioning system (GPS), and Bluetooth technology (World Health Organization, 2011). mHealth interventions are being developed for a vast range of uses, at different levels in the health system. mHealth has been used effectively in developed countries to produce behaviour change for treatment adherence, and for prevention of non-communicable diseases through encouraging weight loss, increased physical activity and smoking cessation (Cole-Lewis & Kershaw, 2010; Free et al., 2011). The use of mHealth is rapidly expanding in low income settings - in 2009, 51 mHealth programmes were underway in 26 developing countries (Vital Wave Consulting, 2009). mHealth interventions have been documented in the following broad categories (Akter & Ray, 2010; Krishna, Boren, & Balas, 2009; Vital Wave Consulting, 2009):

- 1. Remote data collection (e.g. drug stocks/supplies and health surveys).

- 2. Disease and epidemic surveillance (e.g. weekly numbers of influenza cases).

- 3. Diagnostic and treatment support (for both health-workers and lay public).

- 4. Patient monitoring/recall (e.g. drug adherence, appointment reminders. Can be two-way

- 5. Education and awareness (e.g. HIV education, smoking cessation support).

- 6. Provider training and communication.

mHealth in a PNG context

A rapid increase in cell phone towers has occurred in PNG over recent years, meaning that although much of the country is still inaccessible by road, about 3 million people (or half the population) in PNG now have mobile phone reception. Until now, the use of eHealth technology has been extremely limited in PNG due to almost non-existent communication infrastructure. According to World Bank data, in 2009 there were only 0.9 fixed telephone lines per 100 people in PNG, and in 2007 there were 1.9 internet users per 100 people (World Bank, 2011). The advent of mobile phone technology thus offers exciting potential to utilise mHealth technology to benefit communities in PNG. Licensing requirements for cellphone providers have been used as an instrument to improve equity in access, by insisting that new providers provide coverage to not just densely populated areas.

A pilot initiative to improve the reporting of outbreak prone disease in 10 sub-national centres was recently conducted by the National Department of Health and the World Health Organization. The existing system relies on weekly telephone calls to provincial hospitals, with limited compliance. The trial sites were issued mobile phones installed with a simple reporting template for either immediate or weekly reporting. In addition, this new technology was accompanied with a "package" with 3 components: 1) training on disease surveillance, 2) sample collection materials and 3) a resource folder with tally sheets and guidance on reporting using mobile phones. Health authorities aimed to provide sites with feedback reports so they could see how their data were analysed and fitted into the national picture. However, the development and distribution of surveillance bulletins was sporadic. Timeliness and completeness of reporting improved, and district data was available in "real-time" for the first time in Papua New Guinea. Shifting the responsibility for reporting outbreak prone diseases from the provincial health office to hospital clinicians was seen as a useful step in improving reporting timeliness, completeness and accuracy. The role of "supportive supervision" and feedback in improving data collection should not be underestimated, especially for district level staff who commonly collect and report data with no feedback at all. At the time of writing, a formative evaluation of this initiative planned, with a focus on the timeliness and completeness of reporting. Health outcomes were not included in the evaluation scope.

A number of other mHealth pilots are currently underway in PNG, delivered by a range of agencies. These include the Papua New Guinea Sustainable Development Program (PNGSDP) who are conducting village surveys in the remote Western Province, and the Clinton Global Initiative, who have developed a printing device than can be activated by a cell phone signal so that essential laboratory results (especially in relation to HIV/AIDS) can be instantly transmitted from the central laboratory to a more peripheral clinic. The Asian Development Bank is testing the use of cell phones to undertake a survey of health facilities in remote areas, and to support the collection of data on maternal deaths. No evaluations of these interventions were available at the time of writing.

Some of these initiatives are yet to be developed to the point where they can be linked to the national health data collection system. This linkage is important as not doing so risks developing parallel data collection systems and undermining the already weak National Health Information System (NHIS). If the efforts going into these stand-alone data collection initiatives are not also going into building the capacity of the NHIS, then this is a missed opportunity for health system strengthening in PNG. National co-ordination of these multiple initiatives is also important to avoid duplication and to ensure that a common platform is developed that can support all of these purposes. For example, the critical device is the handheld cell phone which needs to have sufficient capacity and access to run a variety of applications to avoid, for example, the unfortunate situation of health workers needing to carry two mobile phones for two separate programmes. It is clear that a number of current initiatives have the potential to support priority health outcomes such as reducing maternal mortality; however, planned evaluation is limited to timeliness and accuracy of data flows.

Although not exclusively mHealth interventions, other developments in mobile phone technology offer the potential to improve health system performance, and quality of life for communities in PNG. Upcoming initiatives, such as "mobile money", will allow funds to be transferred electronically via mobile phones, reducing the transaction costs and risks involved with relying on cash. Currently health workers in remote areas are spending many days travelling to the nearest bank to collect pay - with the technology changes, the need for such trips, and time away from work, could be reduced. This technology will also facilitate the sending of remittances from urban centres to family members in rural areas. However, new mobile phone technologies cannot work by themselves - they require supportive changes in a broader ecosystem. For example, a technology may exist to send funds via mobile phone to family members in remote villages, but if the village store does not also support the new technology, then "electronic funds" on a mobile phone will be of no practical use to villagers. The technological innovation is only one part of the intervention. National co-ordination could help ensure that these exciting new technologies are used for the most pressing needs identified in the National Health Plan and in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Evaluations of mHealth impacts in complex health systems

International mHealth EvaluationsTo date international mHealth evaluations have been small and not focused on health outcomes, the impacts on equity or the effects on the broader health system. A recent systematic review of evaluations of eHealth interventions in developing countries (J. A. Blaya, Fraser, & Holt, 2010) concluded that mHealth devices can be very effective in improving data collection time and quality (J. A. Blaya et al., 2010). Data collection systems are the most evaluated of all mHealth interventions (J. A. Blaya et al., 2010), but evaluations so far have focused on process indicators (e.g. number of text messages received) or user attitudes to the technology, rather than patient health outcomes (H. S. F. Fraser et al., 2004; Rotich et al., 2003).

No mHealth evaluations have considered impacts on the broader health system other than cost-effectiveness studies of the mHealth system compared to the original system (J. Blaya, Holt, & Fraser, 2008; Mahmud, Rodriguez, & Nesbit, 2010). A 2005 WHO report noted that innovations in information and communication technology (ICT) come mainly from the private sector and do not necessarily reflect health sector priorities (Dzenowagis & Kernen, 2005). Adoption of mHealth technologies in the health system often occurs without comprehensive evaluation of the health impact or a true understanding of the added value of ICT to health system functioning (Dzenowagis & Kernen, 2005). Evaluations have not considered whether mHealth interventions lead to any unintended negative consequences, including widening health and social inequities. Rigorous evaluations are urgently required to ensure these interventions are safe, improve health outcomes, are equitable and not a waste of scant resources (J. A. Blaya et al., 2010; Rigby, 2002).

Evaluation of mHealth in complex systems in PNGHealth equity is especially important to consider when evaluating mHealth, as new technologies can widen health inequities by failing to benefit those in the greatest need. However, currently there are no mHealth evaluations in PNG that consider the impact on community health.

The successful implementation of mHealth depends on a wide range of factors in the broader health system. mHealth could also have unforeseen effects on other aspects of health system functioning, and it is crucial that such implications are considered and detected. For these reasons, evaluation of the discrete mHealth interventions is important. However, mHealth interventions do not operate in isolation; as described above, they are part of a complex system. There also needs to be a way of considering whether and how the combination of all components/sub-systems leads to the overarching system objectives of improved community health and health equity. Questions, such as how factors in the rest of the system limit or support the success of the mHealth intervention, or whether mHealth intervention has unforseen implications for other aspects of the health system which affect its ability to improve population health, need to be answered.

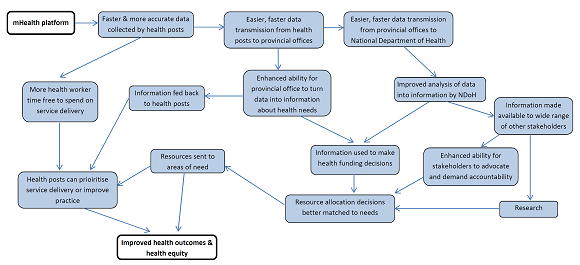

The model in Figure 1 begins to explore some of the connections and processes in the system that could influence whether or not mHealth produces a positive impact on health and health equity. Many more connections and processes will no doubt exist. There will be effects occurring in multiple directions, with feedback loops. Any evaluation needs to be able to identify which step in the system needs to be addressed or improved in order to ensure the whole process works as desired. Any evaluation of mHealth in PNG must consider these factors as they are critically relevant to the success of the mHealth intervention, and in achieving the health and health equity goals for PNG.

What is needed to ensure mHealth meets the health needs of all communities in PNG?

Reflections from a key stakeholder workshop in Port Moresby in 2011A workshop was held in March, 2011 in Port Moresby to consider the implications of mHealth interventions for the broader PNG health system, and to discuss the importance of evaluating and co-ordinating these new initiatives to ensure that these new technologies contribute to improved community health outcomes and health equity.

The workshop highlighted the need to understand the complexities of the system, evaluation challenges and ways forward and an urgent need for better coordination of the multiple mHealth initiatives emerging in PNG so that these developments are used to enhance rather than undermine local NDoH data collection capacity, share learnings, resources and prevent duplication, and work towards the development of common platforms. The various issues raised at the workshop, are discussed in detail below.

The workshop was convened by the National Department of Health (NDoH) in association with the Australian National University. It was funded by a grant from The Trust Company as trustee of the Fred P Archer Trust, and was attended by 14 representatives from the NDoH, University of Papua New Guinea, the World Health Organization, the telecommunications industry, and the Asian Development Bank. Source: (BJ Loring et al., 2011).

Understanding the complexities of the systemmHealth is being introduced to PNG because it is anticipated that there will be positive benefits to the health of people in PNG. The new technology has the potential to rapidly and cheaply improve the amount, quality and speed of health data that are sent from health facilities to provincial and central government agencies/donors. This in turn should enable health decision-making to be based on more accurate and up-to-date-information, and, in theory, reduce the time that scarce front-line health workers spend on administrative reporting. Increased health worker availability should improve access to quality health care, thereby improving health outcomes and reducing health inequalities in PNG. In addition, it may enable timely data to flow in the context of extreme human resource challenges.

These effects assume there is a simple chain of action. In reality, the success of mHealth in PNG, as elsewhere does not come down to one simple, linear relationship. Discussions at the workshop recognized that mHealth is a component or "sub-system" of the broader health system. For mHealth to have a positive effect on health, it first needs to be a quality technology that works, and it needs to be implemented properly. Then, even if the technology works perfectly, and is rolled out in PNG according to plan, whether or not it leads to any improvements to PNG health status will depend on a chain of other factors in the remainder of the health system. If the data collected are not accurate or representative, or not analysed, or the information is not actually used in decision making, then having more data flow faster will not necessarily improve health. Having better data is not sufficient if the capacity does not exist to analyse and interpret all this extra data into meaningful information in time for decision makers to use in their decisions. Having better information will not be sufficient if evidence does not feature strongly in decisions about health spending. The logic of how mHealth interventions could lead to improved health outcomes in PNG is outlined in Figure 1.

Evaluation - what questions should mHealth evaluations ask?

Defining clear goals, both the broader health and health equity goals, and the intermediate objectives that the mHealth technology is going to assist with on the way to realizing the broader health goals, is a critical first step. Evaluation questions need to consider the equity of impacts at all levels of the evaluation. Health inequities result from the combined effect of smaller inequities in acceptability, access and effectiveness at every level in the health system. Each question throughout the evaluation should consider whether mHealth is working and whether it is working fairly.

The types of questions that evaluation needs to be designed to answer include:

- 1. What is the intervention? (What else is in the intervention "package" in addition to the technology, e.g. training, encouragement?)

- 2. Is the technology working as planned? (Are there any unforseen technical problems, such as lack of power supply etc.?)

- 3. Is the intervention being rolled out as planned? (Are there delays, or gaps in access, and why?)

- 4. Are the immediate goals of the technology being met? (For example, more timely data collection, more accurate data, more efficient use of front-line health-worker time, reduced cost of data collection etc.)

- 5. Is it supporting (or detracting from) better integration and functioning of the national health system? Does the system have a clear objective and will the ICT solution help it achieve this? Was there consultation with all programs regarding the data collection burden on health staff? Can this system be integrated with existing systems (at each level - collection, collation, analysis, interpretation, feedback)? Does the system actually need an ICT solution (are data solely for monitoring purposes where timeliness is not crucial)?

- 6. Are the intermediate health system goals being met? (For example, decreased isolation and empowerment of front-line health workers, better use of information in health sector decision-making etc.)

- 7. What are the impacts on broader health system goals? (For example, reduced maternal mortality, reduced health inequalities, reduced fragmentation of health system etc.)

- 8. What are the impacts of the technology on the community as a whole, and what is the capacity in the community to effectively use these technologies?

Evaluation questions need to be of interest to providers and the evaluators, and questions must be measurable, with baseline quantitative data (Mahmud et al., 2010). Evaluations should include measures of user satisfaction, and data quality - including comparing electronic data to original documents at clinical sites (H. S. Fraser & Blaya, 2010). However, as mentioned above, evaluations need to go beyond this if they are to determine whether mHealth interventions are having beneficial and equitable impacts on the health of the population.

Methodological considerations with mHealth evaluationsEvaluation is not something that should happen at the last stage - to be most useful it needs to occur right from the beginning of the programme. A formative evaluation provides feedback as the technology is being introduced; this enables changes and improvements to be made along the way. A summative evaluation examines whether the technology has achieved its objectives, and what the broader impacts (positive and negative) have been. As with any new technology, there are risks that mHealth may in fact make some problems worse, e.g. by taking up more time and resources, or by exacerbating health inequalities through benefitting the population unevenly. An evaluation will help detect any unintended consequences early, so something can be done.

Past mHealth evaluations have included both qualitative approaches (using questionnaires, focus groups and interviews to seek users' opinions) and quantitative approaches (investigating data quality, administrative changes, patient care and economic aspects) (J. A. Blaya et al., 2010). Most mHealth evaluations have taken a descriptive qualitative approach, although more quantitative analyses are being performed as interventions become larger and more established (J. Blaya et al., 2008).

To be able to determine whether improvements in data quality or patient care are actually due to the mHealth intervention, and not other factors, evaluations must carefully control for sources of potential bias (J. Blaya et al., 2008). For example, staff behaviour changes when they know they are being studied. Controlling for sources of bias is difficult, but if an evaluation is not conducted to produce credible results, then it is a waste of resources. Given these challenges, evaluations of mHealth technologies require significant resources to be successful. Most evaluations in low income settings have been conducted by academic institutions. It is beyond the capacity of academic institutions in resource-poor settings to undertake mHealth evaluations that are large or robust. There is therefore a pressing need for mHealth evaluations to be included in the implementation budget and covered by donors/funders (J. A. Blaya et al., 2010; J. Blaya et al., 2008). Evaluations are more likely to be effective if they involve collaborative knowledge production between researchers, practitioners, and funders from the development stage through to implementation and evaluation.

In a practical sense, there are three main options for evaluation study designs for mHealth interventions (J. Blaya et al., 2008):

- Historical controls ("before and after" studies) - healthcare systems change quickly, and improvements could be due to other factors. Baseline data needs to be collected if none exists.

- Randomised clinic controls - involving some clinics using the new system and some which are not. It can be difficult to find equivalent clinics/communities to compare. Multiple clinics to necessary achieve large enough sample size.

- Pragmatic "hybrid" approach - carry out before and after comparisons in the interventions sites, and also use areas where new system has not yet been introduced as controls.

The following lessons from implementing eHealth interventions in low income settings (H. S. Fraser & Blaya, 2010), are relevant not just to the introduction of mHealth interventions, but are also important to consider in designing an effective and workable evaluation:

- 1. Avoid "systems that just suck" where data are pulled centrally, with no feedback or direct benefit to those inputting the data. For staff to invest precious time in collecting quality data, data collection needs to be useful and relevant to their local work.

- 2. Individual patient records need to be kept for quality aggregated data - aggregated data are of interest to decision-makers, but unless basic individual records are kept (either on paper lists or electronically), it can be difficult for staff to keep track of the large number of people seen each day.

- 3. Local leadership is critical for success - new systems cannot be expected to work unless local staff has a real stake in the entire process. Local champions can help foster acceptance, as can introducing interventions at the same time as other system improvements.

- 4. Use existing data where possiblewhere possible, mHealth evaluations should use routinely collected data from logs or other sources, rather than requiring new collection (Puskin, Cohen, Ferguson, Krupinski, & Spaulding, 2010).

Conclusion

In introducing any new health technology, the overarching objective should be to improve community health outcomes and health equity. mHealth offers tremendous opportunity to facilitate rapid and large scale improvements in the PNG health system, with the ultimate objective to improve health and health equity for the people of PNG. mHealth interventions do not operate in isolation, but occur in the context of complex health systems. The successful implementation of mHealth depends on a wide range of factors in the broader health system. mHealth could also have unforeseen effects on other aspects of health system functioning, and it is crucial that such implications are considered and detected. For these reasons, any implementation of mHealth needs to be evaluated. Evaluation needs to start from the beginning of the programme, involve multiple stakeholders including users, and be sufficiently resourced to look beyond the immediate, one-dimensional measures of success. Health equity is especially important to consider in the evaluation of mHealth, as new technologies can widen health inequities by failing to benefit those in the greatest need.

Acknowledgement

Financial support for this paper was received from The Trust Company as trustee of the Fred P Archer Trust, Australia.