In Taking Back Our Spirits , Jo-Ann Episkenew (2009) writes of the significance of indigenous literature as a "medicine" in healing the wounds of "colonial contagion." This healing process, according to Episkenew, is articulated through the spoken and written words of Aboriginal writers. These counter-narratives challenge what she terms the master narrative of the settler: the national myth of Canada which "valorizes settlers but which sometimes misrepresents, and more often excludes Indigenous peoples" (Episkenew, 2009: 2). Here we examine the value of digital story-telling as a similar kind of "medicine" that, as counter-narrative, communicates both suffering and healing as much in their telling as in their production, distribution and consumption. Health information and communication technologies are without doubt transforming the healthcare and social landscapes of many Aboriginal communities today (Beaton, O'Donnell, Fiser, Walmark, 2009). Yet as much as e-health technologies are valuable and empowering (Gideon, 2006) there is an interventionist model ascribed to them and with it a presumption that the technology is predominantly for data transmission rather than as a resource unto itself. Further, the experience of Aboriginal communities, and especially those that are marginalized, is that there is the potential for health innovation to be viewed less as an advancement in health care provision than as another form of encroachment of settler technologies and surveillance.

Here we offer an alternative perspective on digital technologies as creatively engaged tools of healing and empowerment in ways that effectively challenge issues of encroachment while at the same time going beyond standard configurations of medical innovation. With examples drawn from on-line sites including My Word: Storytelling and Digital Media Labs , The Toronto Centre for Digital Storytelling (TCDS), Reel Youth and Youth Have the Power we explore the internet, in particular, as simultaneously social space and therapeutic tool i. Indigenous youth are participating in health-related initiatives including the creative representation of Aboriginality through online stories, amateur video production and various forms of file-sharing and communication. These digital projects are not just acts of storytelling or social interaction; they are part of a larger complex of contemporary healing initiatives that must be viewed within expanded conceptualizations of health and health innovation (Adelson, 2000). Health innovation, in this sense, must extend to include the use of information communication technologies as tools to strengthen communities of support and facilitate social engagement with health issues. We include in that engagement studies such as this which seek to offer additional space to broaden the dialogue on the relationship between digital technologies and health.

Note on Terminology : Aboriginality and Digital StorytellingWhile we will use Aboriginality to describe online constructions of "being Aboriginal," we recognize the limitations of the category in that not all First Nations, Inuit or Métis people in Canada use the term or feel that it addresses the diversity within or between indigenous nations. What is shared in the term Aboriginal are the histories and experiences of colonialism and the inextricable link to histories of colonization and de-colonization in relation to the nation-state. Aboriginality attempts to capture the plurality of local and global identities that, while fluid, occur in relation to social, economic and political structures of the nation-state. Aboriginality is, in other words, "for indigenous populations everywhere. . . a claim to distinctiveness based on the assertion of original occupancy, of land rights and the concomitant spurring of colonial influences . . . [it] is the negotiation of political, cultural and social space of Aboriginal peoples" (Adelson, 2001: 80). Aboriginality is thus less a category as it is a political and cultural process (see also Niezen 2003)ii. Digital Stories refers to a specific form of workshop-based storytelling practice that emerged first in California (through the Centre for Digital Storytelling) in the mid-1990s, but which only attained significant global presence in the early 2000s (Hartley & McWilliam, 2009). Digital storytelling projects exist worldwide, although the movement is particularly popular in North America, Europe and Australasia (McWilliam, 2009). Digital shorts are often produced in schools as a pedagogical tool although community centres are another popular site for digital storytelling projects. Digital storytelling focuses on everyday stories told by ordinary people; the accounts are short and autobiographical, combining oral storytelling with images and music to create an aesthetic product and meaningful, often sentimental, narrative. In a review of 300 digital storytelling projects across the world, McWilliam (2009) identifies three common themes which frame community digital storytelling: historical, aspirational and recuperative. At least in the indigenous digital storytelling context, it is nearly impossible to divide digital shorts by these criteria; they are simultaneously historical (authorizing histories of colonization historically silenced by the state), aspirational (providing powerful tools for self-assertion to often marginalized communities) and recuperative (engaged in a process of decolonization and strategies for well-being).

Therapeutic Possibilities of Narrative SharingNarrative sharing through digital storytelling is for many of its indigenous producers and users a powerful and explicit means of engaging in a process of decolonization. The digital stories examined here, for example, present counter-narratives to the Canadian settler state in order to make visible and audible otherwise segmented and silenced experiences of the protracted effects of colonization. Furthermore these digital stories actively highlight and build upon cultural identities and cultural practices as tools in fostering mental and sexual health. Our argument for the therapeutic possibilities of digital storytelling goes beyond what Maggie Brady refers to as the "culture as cure" explanation (Brady, 1995: 1488). While the content within these digital stories themselves provide compelling cases for the importance of traditional practices, dress and language for many Aboriginal people, it would be simplistic to limit the healing potential of these narrative strategies only to a matter of cultural assertion. By overemphasizing a decontextualized notion of culture, one risks romanticizing and essentializing indigenous identities while at the same time potentially undervaluing the therapeutic benefits of digital story-telling. Digital storytelling in itself can be a positive exercise, especially for youth in remote communities facing social and economic marginalization and for those who may not normally have the space, audience or tools to exercise creative agency. Digital technologies are also in and of themselves social and cultural entities that allow youth to participate meaningfully in local and global dialogues.

As valuable as digital storytelling may be there are, to be sure, significant structural limits to its development or expansion. Many individuals and communities, for example, simply do not have the resources to participate in this form of digital dialogue either because of financial constraints or limited infrastructure or capacity. Furthermore, the internet may represent yet another space of colonialism. As empowering as producing a digital short may be, uploading it to YouTube may have a profoundly negative effect, especially if one's project is viewed by internet users with racist or intolerant attitudes towards Aboriginal peoples.

Transformative Power of Digital TechnologiesThe terms "digital storytelling" and "digital narrative" could encompass a seemingly limitless number of genres and forms in the online world. An ethnography of narrative sharing online could include the blogosphere, simulated online worlds, news websites, online magazines, Twitter, or Facebook, to name a few. Such a survey of narrative sharing is well beyond the scope of this article and is steadily becoming a field of research in itself amongst literary theorists, communications theorists, sociologists, and anthropologists. An ethnography of digital storytelling would further require the researcher to be what Walstram (2004) describes as a "participant-experiencer" in the production of these digital stories, involved in the group work, creative planning, filming, editing and local screenings. This project is limited to a textual and visual analysis of select digital stories as a way to identify key themes in the videos and provide a foundation for future research into digital storytelling production by Aboriginal youth. The digital stories examined here were found through internet searches on Google and YouTube with search words such as "digital storytelling," "Aboriginal," "First Nations," "Inuit," and "youth." Here we focus on a specific form of digital stories that has proliferated in the past few years. These digital stories are small in scale and short, typically lasting only a few minutes and are often created by amateur users with relatively affordable equipment. The short videos are playful in form, sometimes jumping from testimony-style segments to street interviews to scripted performances. The stories tend to be autobiographical in form, focusing on the life experiences of a particular person or community (cf. Lundy, 2008) and they are multi-modal in that they layer various levels of audio and visual signifiers to create a particular aesthetic and symbolic meaning: elders may drum to the background of an oral story, while black and white pictures of residential schools may flash across the screen.

Digital short stories are a new method of narrative sharing which holds significant transformative power. As Erstad and Wertsch write: "When a new tool, a new medium, is introduced into the flow of action, it does not simply facilitate or make an existing form of action more efficient. The emphasis is on how it transforms the form of action, on the qualitative transformative, as opposed to facilitative, role of cultural tools" (2008: 27). Digital technologies are themselves reshaping the social institutions and practices surrounding storytelling, including the power relations that govern who can speak, what they can say, and how they can say it. Even using the word "say" to describe storytelling is in a sense misleading considering the communicative transformations presented by digital storytelling. Digital storytelling, with its multimodal structure, demands a narrative analysis that moves beyond texts and language, and considers the semiotic function of images, sound, and performance. As such, we attempt to grasp the effect of digital technologies on the social act of narrative at the local level (i.e. within particular Aboriginal communities), and at the larger global level (i.e. how communities and individuals interact trans-regionally and trans-nationally in constructing narratives). Further, we explore how digital storytelling crafts new modes of communicating authenticity and truths, methods that increasingly rely on image-based testimony. However, this division between local and global is problematic considering how the internet brings with it transformations of cultural conceptions of space, time, and belonging and in that process, transforming too how people make sense of the global and the local, home and away, the public and the private.

In many cases, the internet is not the sole or even primary means through which participants shared their narrative. It is important to note, for example, that while the digital stories examined for this paper were retrieved anonymously through internet search engines, the stories were produced and often distributed within tangible local spaces such as community centres and schools. Reel Youth , for example, organizes local screenings for digital stories produced in their workshops. These Reel Youth Film Festival screenings also promote youth made films from across the country and from partner projects internationally (http://www.reelyouth.ca/RYFF.html). Similarly, the TCDS organizes local screenings for certain projects but also hosts a blog where viewers may watch a select number of videos. Many other young filmmakers still decide against distributing their stories through websites and film screenings and prefer to selectively share among friends and family; the stories, after all, may contain deeply personal content that the filmmakers do not want to widely broadcast. That is, while digital stories represent a new form of computer-mediated communication, they exist within the same social world as other non-digital spaces of communication (panel discussions, circle sharing, local film screenings).

Anthropology, sociology, literary theory and communications studies are all fields in which the concept of narrative has been extensively discussed, though each field differs in its understanding of the concept (not to mention differences within the fields). For our purposes we will keep the definition of narrative as succinct as possible, drawing mostly from existing anthropological literature. Theorists have articulated narrative as a key tool in constructing coherent notion of self, culture, and community, in meaningfully situating experience within one's life story, and in decoding or reframing past experiences in a manner that provides direction for future action (Garro, 2000; Garro & Mattingly, 2000; Linde, 1993). Narrative differs from story in that "narrative" denotes a particular structure or form by which one may communicate the meaning of certain events while story refers to the actual content communicated within that particular narrative form. In other words, narrative is a general structural type, a particular discursive rendering considered meaningful and appropriate within a particular context and through which various stories may be told (Frank, 1995). As Garro and Mattingly (2000: 7) explain, "[n]arrative provides the arena for coming to terms with a problematic experience and making sense, at least provisionally, of what is happening". Narrative is a cultural construct in that the structure and appropriate practice of stories is culturally determined. "Successful" narrative sharing reflects and reproduces broader cultural norms and power relations that dictate when and what stories are appropriate, who can tell them, and how (Ochs & Capps, 1996).

We all regularly tell stories that we feel best communicate ourselves and similarly experience our lives with reference to socially and personally meaningful stories. Narrative is necessarily a relational act that, if performed successfully, implicates its audience in some form of moral action (Garro & Mattingly, 2000). One performs a story not out of random impulse but with a particular intention such that it is not enough for one to simply recount an event; in telling a story one implicitly suggests that there is a reason why this event is significant. Narrative provides the link by tying experiences and events into a coherent notion of who we are within a particular social world.

Episkenew's (2009) concept of indigenous literature as "medicine" to heal the wounds of "colonial contagion" is relevant here. Episkenew refers in particular to narrative as part of a healing process for indigenous individuals and communities. Part of the social production of marginality in colonization is the systematic denial of a morally valued identity to a group of people. In Canadian residential schools, for example, children were forbidden to speak their own languages, to wear their hair long or to participate in their own spiritual practices. Denial of identity was evident too in the way in which the nation-making process not only colonized a territory but re-assigned its meanings through remapping and renaming, effectively erasing other ways of knowing the land. It follows that "healing" from these forms of cultural erasure and silencing demands a social response, including a reaffirmation of Aboriginality through narrative means.

The suffering that endures long past the original colonizing practices goes beyond those that can be addressed by a narrow biomedical approach of curing individual pathologies. While the biomedical approach of "curing" takes disease as the object, in cases of suffering the more holistic approach of "healing" links individual cases of suffering to larger structures of inequality and asymmetrical power relations. Medical anthropologists employ the concept "social suffering" to characterize that which "…results from what political, economic and institutional power does to people, and reciprocally, from how these forms of power themselves influence responses to social problems" (Das, Kleinman, and Lock, 1997: ix). It is not that a group of people are "sick," but that the social and political systems which to a great extent determine one's ability to "be healthy" are themselves "pathological." Indigenous literature, argues Episkenew, can heal the pain of colonization by asserting the competency and experiences of indigenous peoples as well as by awakening the larger settler populations to the sometimes explicit, sometimes subtle, structural forms of violence committed against indigenous peoples.

Digital stories are one way in which Aboriginal people and communities are engaging in this process of narrative decolonization and representation (Perley 2009). We use the word decolonization in a dynamic sense to convey a process of transforming communities and individuals impacted by the enduring legacy of colonial policies, institutions and practices. Decolonization implies a fundamental social and political transformation in indigenous approaches towards still-present policies and attitudes but does not presume Canada to yet be a "post-colonial" state. Digital stories are both aesthetic expressions and a form of resistance through a new narrative genre. One may consider digital stories as what Nancy Fraser (1992) terms a "subaltern counter-public," an alternative discursive space in which marginalized groups may reinterpret and re-imagine identity and community against exclusion from other powerful legal, political or scientific discourses. Subaltern counter-publics are a "parallel public arena where oppressed minority groups invent and circulate counter-discourses to formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests, and needs" (Fraser, 1992: 123). Many of the emerging digital stories explicitly state their intention to rewrite and bear witness to memories that fit uncomfortably with or are explicitly rejected from the master narrative of settler nation states. One example is a digital short produced through the not-for-profit media group Reel Youth . Titled "Residential Truth: Unified Future," (http://reelyouth.ca/residentialtruth.html) the digital short was created with funding from the British Columbia Art Council (Canada) and was a collaboration between Reel Youth mentors and five youth from a Canadian Cree Nation. The digital short concerns the legacy of abuse in Canadian residential schools, focussing in particular on the intergenerational effect of psychological, physical, sexual and spiritual abuses. The short narrative combines black and white photos from residential schools, statistics, oral history and testimony from Lulu, a woman who actually attended the Marieval, Saskatchewan Roman Catholic residential school with the narratives of Cree young adults. One youth, Courtenay, reflects on her education in high school to illustrate the erasure of residential violence in the construction of Canadian history:

That's, you know, one of the things that people don't know is about residential schools and how we're still trying to heal from that [. . .]when I was in high school, the only thing we learnt about residential schools, that was taught, was one page in the social studies history textbook. There was no mention of any of the sexual abuse that went on, or the physical abuse, or even the psychological abuse. And, and, the teachers didn't mention it either, and there's no talk about just the cultural and spiritual murder that went on in those schools (Courtenay, in "Residential Truth: Unified Future", http://reelyouth.ca/residentialtruth.html).

In this inter-generational narrative of residential school, silence is a common thread, a uniting metaphor that connects the younger participants' feelings of "low confidence" and "constant oppression" with violence committed within residential schools. Against the metaphor of silence, the power of being able to "speak" takes on particular and profound importance. Lulu's daughter, Bacilia, tearfully expresses her frustration that she must communicate in a language forced upon her mother in residential school: "I want an apology from the Catholic Church, you know, they get to speak English, and I have to say that's my first language, and it's not - Cree is my first language." "Speaking out," and "telling my story" holds central importance in the account-an act that is specifically identified by Lulu as an essential part of the healing process. Although she directs the majority of her storytelling to an unknown audience-she seems to be speaking directly to the viewer yet is clearly responding to the prompts of an interviewer-Lulu breaks from this style of narration at one point to directly address the interviewer: "I'm thankful that I'm still here to tell you this story, because it has to be known. It has to be known out there. People don't know. And it's time." In acknowledging her intentions, Lulu shifts the viewer from someone hearing the story to someone who must actively engage themselves in the learning/listening/telling process. This may have been an editorial choice to make viewers aware that they are participating in an important story that must be re-told as part of Lulu's healing process. These digital shorts are self-consciously spaces of truth-telling that invite their audience to continue in the social process of narrative healing. In this way, digital stories are a new "counter-public" where suffering can be communicated and where individuals and communities can, through narrative, heal.

Narrative approaches to healing are not unique to online digital shorts. It is important to note that the digital short emerges in Canada during a period in which truth-telling and testimony are key Aboriginal healing strategies. One significant project is the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which was established by the 2006 Indian Residential School Settlement as a means for residential school survivors to share and witness residential school experiences in a public forum (IRSRC 2006). The TRC is not judicial; its purpose is not to find fault or retribution. Rather the focus of the TRC is on reconciliation, specifically focusing on building new relationships through a process of narrative sharing. Similar to the digital stories, the TRC holds that communication of experience within a public venue is an essential part of healing. The TRC seeks to provide safe and culturally appropriate settings for this healing and proceeds from the understanding that "the truth of our common experiences will help set our spirits free and pave the way to reconciliation" (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2006: 1). As Bacilia's sentiments suggest, Reel Youth participants differ from those testifying at the TRC with regard to finding fault and retribution. They nevertheless share a common understanding that narrative sharing about suffering is in itself a healing act.

Identity and the Framing of Sexual and Mental Health & Well-BeingAnother therapeutic possibility of digital storytelling stems from the ways in which youth creatively use these technologies to address mental and sexual health in their communities. Digital shorts are projects that may open dialogue within communities on strategies for well-being, while also allowing youth to communicate their concerns and strategies to a broader audience. Digital stories are not merely creative products with benefits for those who consume them; the process of creating digital stories is in itself an innovative approach to tackling often tabooed social problems such as Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), depression, or drug addiction. Furthermore, digital storytelling provides participants the opportunity to frame sexual and mental health in a manner that promotes Aboriginal community and identity as a source of strength in addressing social issues. A powerful example of this kind of strategy comes from Chee Mamuk , a provincial Aboriginal-focused program at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, which has developed a webpage dedicated to sexual health promotion amongst BC First Nations youth. The Youth Have the Power webpage includes a "Star in Your Own Series" campaign which promotes the active use of digital technologies to enhance and enliven positive health messages. Here we have selected one of those videos, entitled "By My Name", which was created in partnership with the Nak'azdli First Nation, a member of the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council (http://campaigns.hellocoolworld.com/index.cfm?campaign_id=2). "By My Name" is a performance-driven digital short filmed by Nak'azdli youth which explicitly links cultural identity and community strength to sexual health strategies. In "By My Name," the young adults play on the term Carrier to describe how they see culturally strong communities as healthy communities. Alicia, one of the participants, explains what the word Carrier means to her:

When we didn't know any culture but our own, we would cremate our dead and carry them with us for an entire year or longer before we laid them to rest. We were given the name Carrier when other people witnessed this, and we've held it ever since. We carry the knowledge ( Youth Have the Power ).

"We are Carrier people." "Proud of who we are." "We carry the knowledge." As we hear the voiceover that immediately follows Alicia's words, the screen image is of one of the Nak'azdli youth passing a basket of condoms from one to another and another. The image conveys the message that Carrier people are not only "carriers" of their dead ancestors; they are also carriers of other kinds of knowledge, including new knowledge about preventing HIV and supporting those infected with the virus. Linking identity, empowerment and sexual health, Carrier identity is framed as a tool in maintaining and supporting the well-being of communities and individuals.

HIV prevention is framed not only within the language of empowerment but also as part of the larger project of decolonization. As one participant says, "To decolonize, we can do small things like help a neighbour, help a friend, do positive things. We support our people with HIV." While the message in "By My Name", as in other digital shorts, stresses the importance of tradition enlivened through specific cultural practices such as drumming, they are employing innovative technologies to build upon these conceptualized communities of strength and support. This kind of access to powerful tools of communication and the ability to speak and strategize about social problems in a safe and respectful environment is a goal that can benefit indigenous and non-indigenous communities alike. Digital stories, in other words, are projects that open up possibilities for new communities of engagement and support.

While the importance of "truth-telling" through narrative is by no means a new concept, the processes governing how to determine authentic stories and subjectivities change with changing technologies, institutions, and paradigms. In this section we examine shifts in how one effectively communicates authenticity and truth given the proliferation of digital technologies and their electronic distribution. In exploring authenticity, we do not mean to use the term in a way that denotes an essential or inherent quality typifying a person or community. Rather, we approach authenticity as a fluid process by which people and communities construct and articulate subjectivities. As noted earlier, truth-telling and authentic stories are valued highly in digital stories as key to how one communicates experience, suffering and healing. However, in a digitized social world, where images and sound can be manipulated to communicate even the most fabricated events, what processes and tools effectively express a "true" experience?

In order to address ways in which digital technologies are used in the process of communicating experience as true and significant, we draw upon two collections of digital narratives. The first collection comes from Reel Youth who this time collaborated with Beatboardiii and the Inuvik Youth Centre to produce a series of digital shorts featuring youth from Inuvik (http://reelyouth.ca/Inuvik2.html). The majority of these digital shorts focus on individual youth as they discuss everyday activities, ambitions, and participation in community events and practices. Although all the videos emerge from a collaborative process with program leaders and groups of participants, they generally feature one person at a time as both the subject and object of storytelling.

The second collection of digital narratives were produced as part of a community-based research project titled Changing Climate, Changing Health, Changing Stories that sought to understand the impact of climate change on local health and well-being. The project was led by the Rigolet Inuit Community Government in Nunatsiavut in partnership with University of Guelph co-directors Ashlee Cunsol Willox and Sherilee Harperiv. The series is titled "Rigolettimiugvunga" ( trans. "I am from Rigolet") and features stories connected through concerns about climate change and its potential impacts on cultural practices and autonomy. Online text from the TCDS website introduces the stories as place-based narratives that document changing identity, land, health, and well-being:

This digital story collection was created in 2009-2010 as a part of a community-driven storytelling project led by the Rigolet Inuit Community Government in Nunatsiavut. In the project, community members used digital media to create place-based narratives, documenting the impacts of climate change on human health and well-being, and sharing adaptation strategies. Individually, these stories represent poignant personal narratives and observations; collectively, they weave together a rich tapestry of experiences and wisdom that attempt to redefine the borders between science and stories, humans and landscapes. Through our many voices, we invite the viewer on a personal journey through the terrain of Northern Labrador, guided by the stories of Inuit residents from Rigolet. Welcome to our world. (http://storycentre.wordpress.com/2010/02/25/rigolettimiugvunga/, accessed 21 November, 2011)

The videos created through this project are not specifically youth-focused but draw on the oral histories and wisdom of many community members, including Elders. However, the project shares with other youth-focused projects the use of digital storytelling as a tool for identifying, understanding and adapting to changing community needs and was for this reason included here. The project has since flourished and has transformed into the community-run My Word: Storytelling and Digital Media Lab which continues to offer workshops in computer programs, photography and audio-recording. In addition to archiving community knowledge and oral histories, the lab plays an innovative role in communicating information about ongoing health research projects. Further, while the digital stories from these collections were made by Elders, we find that they nonetheless exemplify techniques in digital storytelling which appear as well in youth-focused projects.

In digital stories, establishing authenticity relies on presenting visual evidence of one's experiences. Whether through text or video imagery created by digital storytellers themselves, digital shorts draw upon specific themes and creative imagery to communicate distinctive subjectivities and experiences. This visual evidence need not always be literal to accomplish its task. Rather, digital storytellers frequently use images metaphorically to demonstrate the veracity of an event or emotion. The multimodality of these digital shorts-their ability to combine various audio, image, video and textual components in the narrative process-calls for a rethinking of practices of authorship with regard to narration and subjectivity.

Images and Establishing a "Voice"In their introduction to Remaking a World , a collection of essays on responses to social suffering, Das and Kleinman (2000:5) ask: "How does the availability of a genre mold the articulation of sufferings-assign a subject position as a place from which suffering may be voiced?". Their question is useful in considering how digital technologies and their distribution via the internet create new genre types and how these new genre types produce new methods of presenting subjectivities, voice, and experience. Genre necessarily shapes the meaning and the possibilities of speech. These speech genres provide the framework to a social network of people on how to interpret and make meaning out of a given text (Morris, 1997). In the case of digital storytelling, the communicative success between teller and audience depends on shared values as the personal story is communicating a particular truth about larger experiences. The mantra of "everyone has a story" that underlies the production of these kinds of videos more generally implies that an individual's witnessing or testimony holds social and cultural significance in communicating larger realities. Further, digital storytelling reflects the increasing importance of video imaging more generally in establishing authenticity in suffering.

Digital storytelling as a narrative form relies heavily on combinations of various media in communicating subjectivity. Oral accounts alone are rarely sufficient. Even when the narrator is not visibly present, digital stories such as those from the Rigolettimiugvunga collection display a map to geographically situate the narrator and to locate their subjectivity in time as well as in space. The events and people described in a narrator's testimony establish credibility through streams of images: a black and white photo, for example, authorizes a narrator's relationship to the past, to family members, to a residential school, to a community.

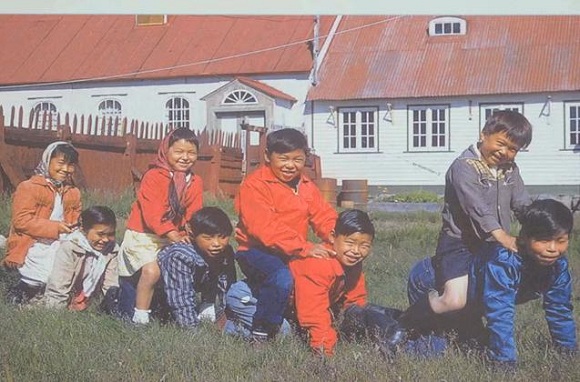

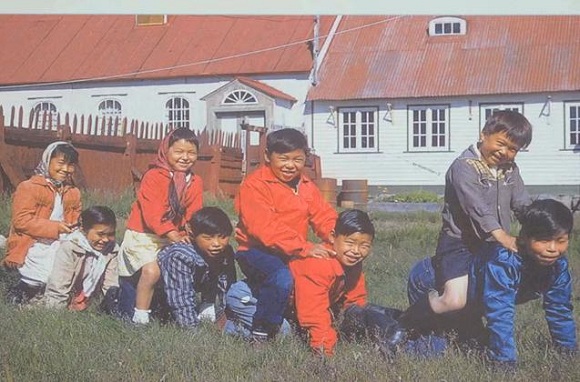

Paradoxically, while digital stories are concerned with capturing the voice of its narrator, they rely heavily on images to substantiate that authentic voice. In one of the Rigolettimiugvunga digital stories, titled "Letting Go of My Homeland," (http://vimeo.com/9719700) a woman named Bertha recounts her community's removal in 1959 from the Inuit village of Hebron, Labrador and the traumatic forced splitting of families through this imposed relocation. She begins by introducing herself as a seven-year old girl at the time of the announcement of the displacement as we see a washed-out early colour image of eight children appearing to play in front of what is either a school or church building. While it is not explicitly stated, the picture serves to authorize Bertha's claims to a childhood in Hebron; the cheerful faces of the children referencing a happy and healthy community (see Fig. 1). As she describes the meetings preceding the community's relocation, images of a church and then members of the community participating in church services flash on the screen establishing the church as a central part of life in Hebron (see Fig. 2). To indicate a passage in time, the digital short employs a black screen separating pre- and post- relocation. Images (as well as their strategic removal), however figuratively they align with the oral account in digital stories, offer cues on how to interpret the text. Certain images, such as that of children playing to indicate innocence, have strong communicative power in establishing the mood of a narrative. While these images have no fixed meaning (certainly an image of a church congregation will invoke a diverse number of feelings in different viewers depending on their experiences with organized religion), certain interpretations gain influential semiotic meaning within specific contexts. A successful storyteller in the context of digital storytelling must draw on not only the right words to invoke sentiments but also the right images.

Digital stories are spaces where users/creators contest and contradict, where one can witness and evoke the tensions of identity. The multimodality of these digital shorts structures them as self-conscious spaces for experimentation in communicating subjectivity and authenticity. Authenticity is necessarily dynamic as multiple voices and images enter the narrative and alter its landscape. The playfulness and often autobiographical form keeps the viewer aware that these narratives are a dynamic process of identity construction, not a fixed authentic moment. In Reel Youth's "Living off the Land," for example, Burton discusses what for him constitutes Inuit culture and why it is important (See Fig. 3; http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hIIFD6x1dMc).

My name is Burton K-----, I live in Inuvik, and I really like my culture because it's how my mom grew up and what she went through to get where she is now . . . something like this is what my mom lived on [pans out to show river and tundra]. She lived on the land. So this is kind of how my mom lived. It's the big river. So that's one of the reasons why I love my culture [runs to pick up stick]. Because you learn how to hunt, and you learn how to live on your own, like. Like, back then in those days there was no grocery store that you could just go to buy what you need. You needed to hunt for what you need to survive. And I just think that if life was still like that, it would be much easier.

For Burton, Inuit cultural identity is attached to notions of the land and hunting for sustenance. He articulates these practices as a source of strength in well-being, citing his mother as an example. His reflections gesture at this conception of Inuit culture as a way of being that no longer exists in such a form. Furthermore, he privileges this way of life as a more ideal form of existence compared to today. Yet, in the second half of the digital short, Burton seems to alter his opinion about living off the land:

When I think about it, like how my mom grew up, I just think: how can so many people just live on the land? Like, survive on their own. It's like, living in igloos and all those sort of stuff. I just can't imagine doing that. No grocery store, no place to shop for clothes, you have to make your own clothes. You have to watch over yourself. Living out on the land, I think, would be the most hardest thing to do in life.

While he feels connected to the conception of "being Inuit" represented by his mother (defined through living off the land and hunting), Burton's account demands a rethinking of this subjectivity. He has never lived and experienced a social environment in which food wasn't accessible at a grocery store or in which he had to hunt for his own food to survive or live only an igloo. The point is all the more evident when considering the medium through which he communicates these sentiments. That he can record and transmit this message from a remote Northern community to the rest of the world is new and seemingly incompatible with a notion of Inuit life that stresses living off the land. Yet consistency is not crucial for the digital story as a genre or for transmitting authenticity; the focus is on capturing a voice within a certain moment, not in finding a definitive description of Inuit or Aboriginal identity. In many ways this focus is a refreshing change from the genres of documentary and older forms of ethnography which aimed to capture an ostensibly objective reality of a culture or community. Digital stories resist such totalizing claims as their focus on capturing voice(s), as fleeting and inconsistent as they may be in any moment. Digital storytelling is fluid, reminding its audience that there are multiple and sometimes competing ways to represent one's truth and one's reality.

Authorship ReworkedDigital storytelling, as a new genre and medium, necessarily brings with it a rethinking of authorship. In the digital short titled "Residential Truth: Unified Future," (http://www.reelyouth.ca/residentialtruth.html), for example, Amber tells an Anishinaabe story originally crafted by Earth Elder, and originally retold by Earth Elder's grandson, Alexander Wolfe. The narrative predicts the confusion and identity loss that would come with the arrival of a foreign culture. What makes the narrative remarkable is that its retelling through digital stories represents a reworking and re-conceptualization of the ways one constructs narrative and with that, authorship. The digital medium serves as not only a conduit for what is an oral story belonging to the Wolf clan. Rather, it effectively reshapes the social practice of storytelling itself: the story gains a new meaning and form when worked into a digital story and in relation to Canada's history of residential schooling. Conventional norms of authorship and ownership of stories is reconsidered in a digital context; the speaker is a youth, not an elder, with the original storyteller referenced through text rather than spoken word. As well, the audience and the narrator are separated across time and space. As such, the anonymous audience may have no other context for the story's significance other than that provided within the digital story, which in this case is a prelude to explaining the pain and suffering caused by the residential schooling system. This digital context may be the only connection between the narrator and viewer. Whereas in oral traditions a shared social event may prompt the retelling of a story and the retelling may confirm or further establish a relationship between narrator and listener, the story's retelling within digital space is removed from any such direct social interaction. The transmission of the story takes on a new form however through, for example, links to websites or social networking sites. Authorship of the story becomes more diffused and plastic in the digital context.

If ICTs are, as O'Donnell and Henriksen(2002: 92) write, "what they are in relation to our use of them, their relation to one another and in relation to the particular situation or context in which they are used", then we begin to understand both the power and limitations of technologies in use. E-health and health information and communications technologies more generally are without doubt transforming modalities and effective management of health care to remote and underserviced indigenous communities where these services are available and sustainable. If e-health technologies are too quickly defined however solely through the delivery of health services, this limits the transformative potential to which O'Donnell and Henriksen are alluding. We suggest that there is as yet untapped potential for health innovation emerging from technologies increasingly (although not yet universally) available in indigenous communities across Canada. In the same way that e-health technologies can be inventively transformed into forums for increased community engagement (Mignone and Henley 2009), ICTs can be reconfigured as modalities of healing as communities creatively engage these technologies. In this paper we have examined digital storytelling as a narrative form of healing, drawing from Episkenew's (2009) concept of indigenous literature as a healing or recuperative process in the larger project of decolonization.

Many communities have found digital storytelling useful in engaging youth in particular in collectively imagining and creating what a healthy and strong community looks like and in discussions, for example, about mental and sexual health strategies. Indigenous youth who participate in these programs are not just reflecting on their personal experiences but actively creating environments in which creativity and communication are increasingly more central to healthy minds, bodies and communities. While the idea of indigenous culture as a source of strength appears frequently in these digital shorts, these creative productions are more than an affirmation of silenced and marginalized voices and practices. Being able to participate meaningfully in a far-reaching initiative has inherent value. Within the colonial context, and during a historical moment in which "speaking out" about social suffering under colonization is gaining momentum through strategies such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, digital storytelling is an innovative approach to challenging the master narrative of settler Canada. Digital stories, as such, may be considered an emerging counter-public in which Aboriginality is being renegotiated and through which strategies for well-being, healing and decolonization are co-constructed through the production and dissemination of narratives online.

Digital storytelling is an important new genre of narrative sharing in that it is transforming the social practice of storytelling. As we found in our review of digital stories, subjectivity, voice and authenticity are all concepts being reworked on the internet as new narrative possibilities not only reshape the social act of narrative sharing but also the genres by which suffering and experience are communicated and through which healing initiatives are enacted. Digital storytelling focuses on capturing voices and on combining multiple modes of signification (such as image, sound, and video) to authorize those voices as authentic even as subjectivities are constructed as purposefully inconsistent and dynamic. Further, conventions of authorship are broken down in the process of creating and distributing digital stories via the internet: authorship is diffused among multiple participants in the creative process as the social act of sharing stories takes on new forms through online social networking.

We have focused primarily on youth-led digital stories mostly because the bulk of digital storytelling projects in indigenous Canada are geared toward a teenaged, high school demographic (cf. Perley 2009). This may have to do with the fact that digital storytelling remains a primarily pedagogical tool in North America but also because digital storytelling is most accessible to a generation that has grown up with the technologies that make it possible. That in mind, digital storytelling is not universally a therapeutic or meaning-making practice in narrative sharing. It is important to remember the limits of digital storytelling: while the infrastructure and tools for digital storytelling is widely accessible to affluent urban populations, many remote and economically marginalized communities do not have access either to the internet or to adequate transmission bandwidth, let alone video recording or editing equipment. Moreover, even if the equipment and infrastructure exists, little existing research examines the benefit of digital storytelling to older and/or more isolated populations. That said, digital storytelling remains a new and innovative approach to narrative sharing as healing in many community centres and schools and will undoubtedly undergo considerable changes in form and expression as new participants experiment with its creative and communicative possibilities. The internet is an important space of social action-and even social healing-and digital storytelling but one of the many new genres emerging from online and offline interaction that must be given ethnographic consideration.

i Prior to publication the authors shared a full draft of this paper with the lead members of each of the teams that produced the videos referenced here. They, along with youth participants Cia, Lulu, Bacilia and Courtney and the director of the Nak'azdli Health Centrewere asked to specifically address the appropriateness of the use of content, images, citations or any other aspect of the videos cited. All have given permission for the use of the content presented here. We note Burton's tragic passing not long after he created the video referenced here. We thank both Mark Vonesch and Erica Kohn for assisting us in our attempt to contact the Inuvik Youth Centre which has, in the interim closed. We also thank Ashlee Cunsolo Willox, Melanie Rivers, Erica Kohn and Mark Vonesch for sharing information and updates with us.

ii Representations of indigenous status and, more importantly, indigenous cyber-activism are already established online strategies as indigenous groups world-wide use digital communications to expand their reach to other indigenous nations and communities and to the wider public (Dyson, et al. 2007; Landzelius 2006; Miller and Slater 2001; Niezen 2005).

iii Beatboard (www.beatboard.org) is a privately run interactive youth education and facilitation program that is, according to its website, "committed to affecting positive change in communities through delivering leading-edge experiential education programs that value diversity, inclusion and solutions for healthy living."

iv The digital stories and further information about the project are available on the community's website (http://www.townofrigolet.com/home/stories.htm). As noted, the community of Rigolet has since created a digital media and research lab in the community where they conduct their own digital story workshops with community members trained as facilitators and have to date produced 34 digital stories (My Word: Storytelling and Digital Media Lab, www.rigolet.ca) (Ashlee Cunsolo Willox, personal communication 2012).