Local democratic values and e-government: barrier or promoter? A case study of a multicultural Swedish municipality

1. PhD Student, Political Science, Department of Management and Engineering, Linköping University, Sweden. Email:gabriella.jansson@liu.se

1. INTRODUCTION

In the light of New Public Management (NPM)1 , increased efficiency demands within the public sector and the alleged individualization in society, the role and function of public organizations has been a much debated issue in recent decades (e.g. Peters 2001; Christensen & Lægrid 2007; Gjelstrup & Sørensen 2007). The development of e-government and the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in public organizations, has added yet another aspect to this debate. E-government is increasingly being emphasized as "the way to 'do' modern government" (Nixon et al. 2010, p. xxiii) and is thus moving beyond mere technology implementation. It is presented as a multifaceted reform with powerful transforming potential, with predictions of its effects ranging from overly pessimistic to overly optimistic. In this respect, e-government embodies both hopes of more efficient public organizations and fears that an overemphasis on efficiency will lead to a neglect of the inherent democratic values of public organizations, such as rule of law and principles of equality, equity and solidarity. The latter perspective emphasizes how public organizations have a specific role and responsibility which differ from that of private organizations, that is, they have a public ethos. The overarching aim of public organizations is to serve the public in ways that ensures the public interest and the common good and not merely to meet economic targets or improve cost efficiency. In order for public organizations to create and maintain democratic legitimacy it is important that e-government reforms do not produce trade-offs in policy aims, which in the long run could jeopardize democratic values (Bekkers & Homburg 2005; Cordella 2007; Gurstein 2008; Kettani et al 2008).

This article sets out to increase the understanding of the relationship between democratic values and e-government reforms, with a special focus on public e-services. Previous research of public administration has highlighted the centrality of values, in particular democratic values, for the existence of a legitimate public administration (March & Olsen 1995; Lundquist 1998; Peters 2001). There is thus a need for a deeper understanding of how e-government is influencing the possibility of realizing different values in public organizations, as well as what dominant values and perceptions become embedded in the implementation of e-government (Åström & Olsson 2006).

More specifically, our aim will be to analyze the significance of local democratic core values for the introduction of public e-services in a multicultural Swedish municipal organization with a strong tradition of developing democratic processes and responsiveness to citizen needs. The following research questions will guide our analysis: (1) How and why are local democratic core values related to the implementation of public e-services? (2) Can local democratic values, crudely put, be seen as a barrier or promoter of public e-services? (3) What are the implications thereof? We are interested in how a municipal organization with, on the one hand, a rather specific and, in several respects, vulnerable socio-economic context (from a Swedish perspective) and on the other hand, a strong emphasis on furthering democratic processes, approaches e-service implementation. Western societies are becoming more heterogeneous, where different preconditions and competences of citizen are not only evident between communities in a country but also within communities. We therefore argue for the need to investigate how democratic values, such as ensuring equality, social justice and fair treatment of citizens, as enshrined in the public ethos, are handled with the increased use of ICT in public service provisions. This is particularly important when populations are becoming increasingly heterogeneous, and as a result, displaying different needs and background competences. We will answer our research questions by applying parts of Sabatier's and Jenkins-Smiths's framework for policy adaptation and change (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith 1993), which focuses the role of core values in processes of change. By doing so, we hope to add to the discussion on how the specific institutional features of public organizations are embedded in or realized through e-government implementation, thus connecting to mainstream debates in public administration and e-government (Fountain 2001a; Bekkers & Homburg 2005; Meijer 2007; Tolbert 2008). More generally, we hope to contribute to research on the democratic potential of e-government.

The democratic potential of e-government has traditionally been regarded to lie in the ability of ICT to create more active citizen participation in the democratic decision making processes of representative democracy but also through more participatory and deliberate forms of citizen involvement in public issues thathave been placed under the overarching concept of e-democracy (Coleman & Norris 2005). However, innovations in e-democracy, such as creating chat forums between elected policy makers and citizens or electronic citizen panels, have been outrun by an emphasis on creating more efficient and accessible public services and information via the Internet, known as public e-services (Åström 2004; Dawes 2008). Private companies, with banks as common examples, have provided a blue-print for how public services can be delivered electronically, often with methods and systems deriving from Customer Relation Management (CRM) (Taylor & Lips 2008). Cost efficiency and customer orientation are central aims in policy documents from the European Union (EU) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), as well as national policy documents on e-government (Government Offices of Sweden 2008; OECD 2009; European Commission 2010). Consequently, e-government, at least in its present form, is often viewed as a tool to enforce the economic logic of market-oriented reforms in public organizations, associated with NPM (e.g. Cordella 2007). At the same time, one of the major aims of e-government is to create a more responsive government: a government that is accessible and citizen oriented, in contrast to the alleged inwards-looking bureaucracy of the past (OECD 2009; European Commission 2010). By removing information asymmetries and increasing self-services, citizens can, from a consumer's perspective, become more empowered. Nonetheless, observers have highlighted the danger of viewing citizens as consumers and governments as "production companies", as that neglects the public and political character of service delivery and narrows the multidimensionality of citizenship and public administration (Fountain 2001b; Aberbach & Christensen 2005; Dutil et al 2007). Citizenship involves certain constitutional rights, which, amongst other things, include access to services on an equal basis. These are especially important for exposed groups of citizens, since they are often most reliant on public services, e.g. social security benefits. To these groups, language, knowledge or competence barriers could obstruct an effective use of public e-services, thus resulting in exclusion rather than empowerment (Dutil et al 2007; Helbig et al 2009). This implies that the implementation of public e-services may have more far reaching consequences than current policy aims of e-government have anticipated and further highlights the need for investigating the values embedded in and realized through e-government.

In advanced welfare states, public services are central for the creation and maintenance of trust for the political system, as well as of democratic legitimacy. To many citizens, the political system is embodied in the public services they meet in their everyday life. The character of this meeting is decisive for how citizens judge the political system. In this respect, an adherence to the rights of individuals as formulated constitutionally becomes just as imperative for creating legitimacy as an efficient administration (Peters 2001; Rothstein 2010). The fact that public services are administrated electronically should not make this aspect less important. According to this logic, public e-services are not only a tool for efficient service management but also a central component in the creation and maintenance of democratic legitimacy. More specifically, this circumstance illustrates the need for broadening the study of the democratic potential of e-government to public e-services. Furthermore, it has become increasingly clear that e-government has become a catalyst for different processes of change in which the complex interplay between the technology and specific local institutional settings does not always produce uniform and anticipated outcomes (Fountain 2001a; Bekkers & Homburg 2005). This means that it is necessary to take the wider polity of "government" in e-government, i.e. its public and political character, into account in order to understand its implementation and possible implications thereof (Meijer 2007; Taylor & Lips 2008).

The article is structured as follows: first, an overview of the methodological considerations of the study will be described. Second, the role of core values in policy adaptation and change will be discussed in order to set the analytical framework. Third, we present an empirical narrative of the process of developing public (e)-services in the studied municipality, Botkyrka in Sweden. Here, the implementation of public e-services will be placed into the longer tradition of organizing and providing public services and information in the municipality (hence the "e" in brackets), thus illustrating the establishment of the distinctive local democratic values. Finally, we draw together the conclusions of the analysis and discuss some of the possible implications of our findings in order to open up the field for further research.

2. E-GOVERNMENT IN A MULTICULTURAL SWEDISH MUNICIPALITY

The intersection between the aspects discussed above is displayed in the case of Sweden. Sweden is not just one of the most advanced countries with regards to e-government developments (UN 2008) but it also combines high broadband access with one of the most developed welfare states in the world. Public services constitute an integral part of most people's lives and enjoy high legitimacy. In fact, the existence of an effective, impartial and universalistic public administration has been claimed to be the most important factors why Sweden displays what has been dubbed a "high quality of government" (Rothstein & Teorell 2008). Within a Swedish welfare context, municipalities occupy a central position. They are democratically elected local entities, have their own tax base and are responsible for publicly financed governmental tasks which cover approximately 70 percent of public administration in total (Montin 2007). Swedish municipalities thus fund and organize a large share of overall public service provisions, such as school, child care and social services, and are, in several respects, the public organization in closest proximity to the citizen. The strong local autonomy of municipalities furthermore gives them much flexibility in e-government implementation: municipalities are to develop public e-services but how and to what extent is up to each municipality (Government Offices of Sweden 2008).

The specific case study took place in the Swedish municipality of Botkyrka during 2009-2011 and is based on textual analysis of central policy documents and reports as well as semi-structured, in-depth interviews with seven municipality officials and three groups of local council members. Process tracing of these sources has been used as the main analytical tool for depicting the development of local core values and their role in the development of public e-services (George & Bennett 2005). Parts of this study, and hence this article, already figure in a licentiate thesis from 2011 (Jansson 2011) but have been amended according to the different research aim of the article.

Botkyrka is a suburban municipality in the Stockholm area of Sweden and has about 81,000 inhabitants, which makes it the 23rd largest of Sweden's 290 municipalities. It is one of the most multicultural municipalities in Sweden, with socio-economic conditions below the average. Over 100 nationalities are represented in the municipality and 51.4 percent of the inhabitants have an immigrant background, i.e. they were born abroad or with both parents born abroad (compared to Sweden at large: 17.8 percent). Botkyrka has in some respects been regarded as a transit municipality for newly arrived immigrants who, after a short stay, move on to other municipalities in Sweden. However, there is a clear divide between the northern and the southern parts of Botkyrka. The southern parts are largely composed of nature reserves as well as some residential areas of single-family houses. Here, inhabitants with an immigrant background constitute 16.8 percent and the unemployment rate is only 2.2 percent (Sweden at large: 9.8 percent). In contrast, in the northern parts, which consist mainly of blocks of flats, inhabitants with an immigrant background add up to 59.8 percent and an unemployment rate of 6.6 percent. Another defining characteristic of the municipality is the constant rule of a centre-left coalition for over 30 years (Botkyrka municipality 2010; Statistics Sweden 2010).

Botkyrka has, in several respects, been portrayed by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) as a model for other municipalities with regards to furthering citizen involvement and participation in democratic processes, mainly embodied in its success with one-stop government offices (SALAR 2003; SALAR 2009). One-stop government offices, also known as "one stop shops", are common public service units where public officials with general competences provide services across administration, authority and sector divisions, placing citizen needs rather than internal divisions into focus. The main aim is thus to avoid citizens bearing the costs of internal divisions by being asked to go from one place to another for obtaining a service or ful?lling an obligation (Lenk 2002). As will be described, Botkyrka is also considered a forerunner in e-government developments in Sweden (SALAR 2009).

Botkyrka, as a case for studying the significance of local democratic values for e-government developments, is interesting for several reasons. It is a local community where democratic processes and responsiveness have had a central place in dealings with citizens and where multicultural and socio-economic conditions have made the specific role and responsibility of public organizations - the public ethos -more obvious and pressing. Furthermore, the advanced level of e-government in the municipality means that it is a forerunner case which could illuminate important and interesting findings for a deeper understanding of the relationship between local democratic values and e-government.

3. VALUES AS INSTITUTIONAL GROUNDS

Values are clearly a difficult concept, both theoretically and methodologically. How is it possible to depict and analyze something which is in the heads of actors or in general often unarticulated and taken for granted? In order to be able to relate values to the implementation of a new policy area, in this article, we will rely on Sabatier's and Jenkins-Smith's categorization of policy beliefs amongst a group of influential actors (advocacy coalitions), where so-called "deep" or "near core" values guide the direction and actions of actors (Jenkins-Smith & Sabatier 1993). Policy areas are thus here conceptualized as belief systems which consist of certain shared basic assumptions that guide policy choices. From this perspective, values are essential - they are the deeply embedded and underlying structures which provide a basis for judgments of situations, actions, objects or individuals. Values are, simply put, what grounds institutional arrangements, formal as well as informal, which, to different degrees, enable or restrict actors in their actions.

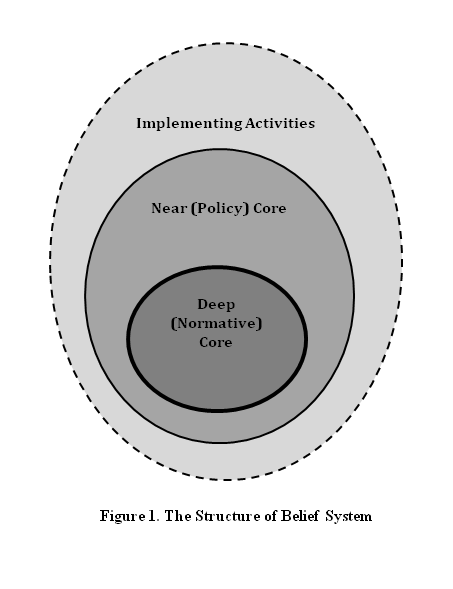

Some beliefs and values are, however, more deeply embedded than others (see Figure 1). Core elements, such as common beliefs, priorities and perceptions of the belief system constrain actors more than others and are consequently more stable over time. This so-called policy core (deep core) involves both personal and normative beliefs, such as common political values according to the left-right scale (equal distribution vs. individual freedom or the role of the state in society) as well as basic policy strategies and aims (near core) for realizing the deep core. In turn, there are also implementing activities (secondary elements), which can be seen as more instrumental decisions or means necessary for realizing the policy core, e.g. administrative rules and budgetary allocations. These are more open to changes over the course of a few years than are the core elements. Nonetheless, both policy strategies and implementing activities are ultimately, more or less, the expression of core values - policy strategies more so than implementing activities. This means that core values are not a completely abstract phenomenon. They are visible as rhetoric in stated policy strategies as well as in more tangible daily activities and practices.

Policy belief systems, and in particular core values, thus provide a cognitive filter for how new ideas are interpreted and implemented. These beliefs are products of past policy choices, which provide meaning for, and legitimize, new policy choices. This does not necessarily presuppose a static scenario where actors continue along the same path. Reforms that match existing belief systems are more easily accepted by actors and can lead to gradual policy learning. In these instances, belief systems facilitate change and allow for a more effective implementation of reforms without changing core values. In turn, certain changes in the external environment can cause a re-evaluation of belief systems and thus gradual policy adaptation. If the pressures are strong enough, a change of core values also occurs. However, as actors are confronted with new ideas, they tend to respond in a manner consistent with the policy core, committing resources and arguing for their cases in order to defend the core. Thus, adaptation and change is motivated by an ongoing process to realize core values (Jenkins-Smith & Sabatier 1993).

To summarize, our analysis will rely on the assumption that institutions can be viewed as a hierarchy of different beliefs which either facilitates reforms or constrains them. As public e-services are implemented in Botkyrka, the reform is placed into the local institutional setting of the municipal organization, which is viewed here as a belief system for organizing and providing public services. In this belief system, specific local democratic core values have been prominent. Next we will turn to analyzing what characterizes these local democratic values and how they have been related to the implementation of public e-services.

4. THE PROCESS OF DEVELOPING PUBLIC (E)-SERVICES IN BOTKYRKA

The following section will be organized into two sections. The first section will give an overview of the institutionalization of democratic core values in Botkyrka, and what signifies these. In the second section, the relationship between the local core values of the municipal organization and the process of developing public e-services in the municipality will be analyzed. The "e" will be placed into the process of developing public service provisions in the municipality. It should be noted that all the interviews were conducted during the end of phase two (2009-2010) and in the instances where interview candidates are quoted earlier, they are retelling previous events.

4.1. Institutionalizing One-stop Government Offices (1987-2000)

In the mid-1980s, it became increasingly clear that Botkyrka was struggling with a number of socio-economic problems such as high unemployment rates, low turnout in public elections and low trust for public institutions. According to a leading council member, the socio-economic situation was regarded a potential "time bomb" (Interview A). In order to counteract alienation and reduce the gap between citizens and the municipal administration, the local council concluded that the municipality needed to become more available to its citizens. Officials in Botkyrka had studied the development of one-stop government offices in Denmark and reached the conclusion that it could be used as an instrument to address the problems Botkyrka faced at the time (Botkyrka Municipality 1994). Because of the high number of inhabitants with an immigrant background, a variety of different needs with regards to access to public services was apparent, in particular for inhabitants with no or little knowledge about Swedish society. There was thus a need for a flexible and customized provision of public services and information, which could be attentive to the specific needs of the local community. The first one-stop government office - also the first in Sweden - was opened in 1987. A notion of an open and physically available municipality in close proximity to citizens and in tune with local needs was emphasized here. The municipal leadership reasoned that an improved dialogue with citizens and an increased service orientation would improve trust in the municipality and in public institutions in general, as stated in policy documents:

Democracy presupposes trust for public institutions. Poor public services lead to frustrated citizens and undermine the preconditions for a democratic society... The offices create prerequisites for citizen engagement, for instance by accommodating service supplies to the needs of the clients... (Botkyrka Municipality 1994)

Over the years, Botkyrka has consistently developed their offices in close proximity to local needs. For instance, interpreters have been made available at certain office hours. The offices have also offered help with issues that are not directly linked to municipal issues but to other public authorities, e.g. health care or social insurances, as well as general questions concerning, for instance, bank loans. For newly-arrived immigrants with extensive need for basic information on the functioning of Swedish society and public services, the municipality has, through the one-stop government offices, functioned as the gateway to Swedish society in general, and public institutions in particular.

In addition, the one-stop government offices have increasingly become a forum for political dialogue and democratic processes, for instance through meetings between citizens and local councilors but also as early warning systems for certain local problems. Several of the interviewed municipality officials emphasize the importance of providing services and information that citizens trust and that are adapted to local needs, both for service and democracy purposes. A report from 2000 states that "...little knowledge of the Swedish language or Swedish society demands external information which is shaped and customized to local needs" (Botkyrka Municipality 2000).

Whereas the offices were initially seen as one way of solving a problem and meeting certain needs, the municipal organization has incrementally been built around the offices. According to one higher official, the offices have become "...a giant system for creating engagement, participation and involvement" (Interview D). Consequently, a consensus of that "this is the way we work in Botkyrka" has been established. This has been termed the "Botkyrka spirit". It is interpreted locally as a municipality in proximity to the citizen with an aim of improving openness, availability and dialogue (Interview E). In turn, the work in Botkyrka has acquired national reputation: few one-stop government offices do such extensive work as the offices in Botkyrka (Öhrling PricewaterhouseCoopers 2002). The offices, in several respects, illustrate activities which go beyond the prescribed responsibilities of Swedish municipalities.

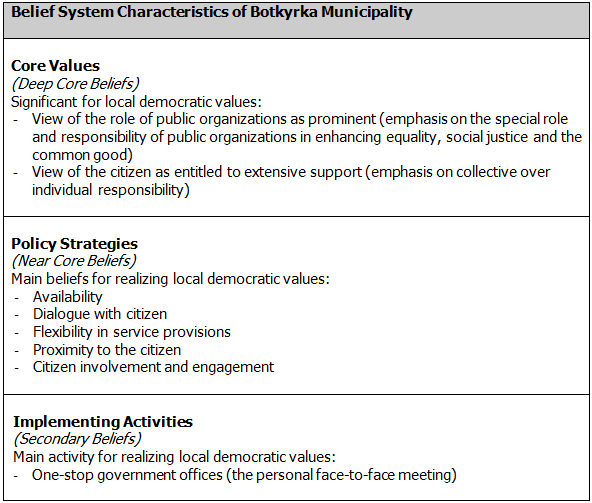

In sum, this period is characterized by the process of institutionalizing one-stop government offices and a specific belief system of providing public services and information accordingly. The time before the development of the offices led up to what we view as a critical juncture, where deteriorating local socio-economic conditions created a realization that the municipal organization needed to have a more active role in supporting and communicating with citizens, both through service and democratic channels. With the development of the one-stop offices, the institutionalization of a belief system began to take place both in rhetoric and in practice. This belief system is summarized in Table 1:

In this belief system, availability, dialogue with citizens, flexibility in service provisions (adjusting to nuances in local needs), proximity to the citizen, as well as citizen involvement and engagement are emphasized as important beliefs. In turn, the local democratic core values during this period signify a view where the role and responsibility of public organizations vis-á-vis the citizen is prominent. The practices at the one-stop government offices illustrate a basic notion that not all citizens have the same preconditions but that some require extra support. Thus, in order to further democratic values such as equality and fair treatment (including equal access to public services) addressing these differing preconditions is considered essential. Acquiring public information and services is hence a collective responsibility and not solely up to the individual. The idea of building trust and democratic legitimacy, in order to facilitate the work of the municipality and contribute to societal integration of citizens, seems to have been decisive in developing the offices. Our analysis shows that there are certain elements of a communitarian view of democracy, in which the significance of the community's role in shaping possibilities of citizens and enhancing the common good is recognizable. However, during this period, focus is still on public services as embodied in the personal face-to-face meeting and ICT does not yet have a central role in public service provisions.

4.2 Towards a Web-Based Municipal Portal (2000-2010)

The development of the one-stop offices seems to have paved the way for innovative perspectives on the provision of public services, with a search for new ways of furthering availability. In the beginning of the 21st century, key actors within the municipality started to discuss ICT in a service application context, which indicated a view of ICT as useful not only for internal administration or for, as in the 1980s and 90s, one-way information but also for two-way interaction between citizens and the municipality in the form of self-services. Inspired by international and national developments, as well as developments in e-banking, ideas for how e-services could be transferred to the municipal context were triggered. Botkyrka became involved in the activities aimed at becoming a "24/7 agency". ICT was associated with an increased service supply, availability and an active dialogue with citizens (Botkyrka Municipality 2002).

In 2003, the municipality carried out an inventory of which municipal services could be offered as e-services. This marked the beginning of concrete activities for making e-services an integral part of service and information provisions (Botkyrka Municipality 2003). E-services and one-stop government offices were regarded as supplementary: both were stressed as means for improving availability, responsiveness and hence, the quality of service provisions. At the same time, experiences from the one-stop offices guided e-service developments, since e-services, just like issues handled at the offices, also involved regular, simpler and routine like procedures. The two service channels were, in certain respects, regarded as "the same thing", as a high-level official puts it in an interview (Interview D). With e-services, the municipality could become even more available and reach a wider spectrum of groups, which correlated to an earlier reasoning where flexible and available services according to local needs had been highlighted.

The initial steps of integrating ICT into information and service channels were rapidly followed by more in-depth and long-term ambitions. The development of an e-strategy, a policy document for the whole municipal administration, in 2005/2006 illustrates a vital step forward. Significant for the e-strategy was how e-services were integrated with the other service channels, generally labeled as a "channel strategy". This meant that the municipality prioritized three channels for contacting the municipal organization: the municipal website (via e-services), the contact centre (via telephone, e-mail, letters and fax) and the one-stop government offices (via the personal meeting) (Botkyrka Municipality 2007). Nevertheless, the centrality of the web was concurrently highlighted:

The web is the most cost efficient channel with highest accessibility, while the personal meeting costs most in terms of resources. Citizens and other interested parties should be able to choose the channel which suits them best in the individual case, but we should steer them towards the most cost-efficient channel (Botkyrka Municipality 2007).

The quotation illustrates the intent to make Internet the main channel for contacting the municipality and cost efficiency as a salient reason behind it. The contact centre and one-stop government offices are here meant as supplementary channels for those who cannot or choose not to use the Internet. Similarly, the continuation of a previous reasoning is noticeable in the e-strategy, where e-services are said to be guided by the same aims as one-stop government offices, that is, increased citizen advantages, customer focus, availability, effectiveness and dialogue, as well as greater openness and transparency (Botkyrka Municipality 2007). This illustrates how the aims of one-stop government offices continued to govern how the municipality viewed and managed public services delivery.

In the years after the e-strategy, ICT increasingly became essential for handling the delivery of public services and information, for instance, library services, school and building permit applications or availability functions for disabled were now available on the municipality website. The pace of e-service developments in several ways picked up with more advanced e-services, such as an Internet portal for school and child care services, as well as, more recently, the development of a web-based municipal portal (Botkyrka Municipality 2008). When logging into the portal, one's role as a citizen or municipal employee will determine the kind of information or e-services one reaches. The portal is based on different divisions of roles, either according to tasks (e.g. applications for schools), area of residence, the division of general municipality activities (e.g. "Businesses" or "Building and Living") or more overarching roles (e.g. "Parent", "Visitor" or Youth"). This categorization of roles illustrates the intention to create personalized e-services that provide flexible access to public information and services no matter the time or place. In turn, citizens are meant to become more self-propelled in their dealings with the municipality. The portal is concurrently emphasized as a way of offering more of the municipality (Botkyrka Municipality 2008). This rhetoric illustrates a continuation of previous policy strategies, i.e. the emphasis on a prominent and responsive municipality that works in proximity, and is available, to the citizen.

However, it is obvious that the e-services and the web portal have not incorporated certain needs of the local community, for instance with regards to language requirements. Swedish is the only language available on the web. The one-stop offices are here meant to accommodate the needs which the web does not. Yet, from a citizen perspective, conducting certain public services on the Internet is appreciated. Internet penetration in the community is high: 91 percent have access to Internet at home (Markör 2011). A survey from 2009 shows that 64 percent of the Botkyrka inhabitants prefer to get municipal information and services via the municipality web page, compared to 42 percent via the one-stop offices (SKOP 2010). However, as these numbers indicate, the one-stop government offices still inhabit an important role in the municipality's services. Also, it is not a question of either/or - many citizens regularly use both channels. The number of errands in the offices has furthermore not decreased and continues to concern public as well as non-public issues. The municipality thus persists to provide services outside the mandatory responsibility of Swedish municipalities. According to a high-ranking official, there will always be a need for face-to-face meetings in Botkyrka, because of the relatively significant group of citizens in need of special guidance, concerning language issues or information in general: "There have to be ways for those who need a personal meeting and it doesn't have to concern only old people... but it can concern complex questions too" (Interview B). Thus, even though Internet penetration is high, there is an awareness that e-services might not be for everyone or for every type of service. There is a specific flexibility in the face-to-face interaction, which the offices can accommodate. It is concurrently clear that the development and continuation of the one-stop government offices have partly been possible through the continued role of a centre-left coalition in Botkyrka. The centre-right oppositional political parties have been critical of the extensive help given to the citizens through the offices.

To summarize, the process shows that the web-based portal continues to build on the belief system and hence local democratic core values created through the previous one-stop approach. E-service implementation is motivated through rhetoric which builds on, and is actively connected to, beliefs such as an extended role of the municipality as well increased availability, dialogue and flexibility in the relationship with the citizen. Availability and personalized services are through e-services meant to be taken to a new level. However, "personalized e-services" implies very broad, simplified and pre-determined roles. In contrast, the offices, through the personal face-to-face meeting, are able to capture more of the nuances in varying citizen needs, e.g. language requirements. Thus, whereas the offices are flexible in the sense of adjustment to personal needs and situations there and then, the portal and e-services are flexible in terms of easy access. Nonetheless, during this phase, the practical realization of e-services as the most central service and information channel takes place. E-services thus fit, at least rhetorically, earlier reasoning according to the Botkyrka spirit.

5. DISCUSSION

The above narrative indicates how the local democratic values of Botkyrka, in which the prominent role and responsibility of public organizations in furthering equality and social justice is emphasized, continue to inhabit an important place in the implementation of e-services. This is in line with Sabatier's and Jenkins-Smith's view on core values as persistent. In the following sections we will, with the help of our theoretical framework, discuss further how and why local democratic core values have been related to the implementation of public e-services, whether these can be seen as barriers or promoters, and end the discussion with a number of observations concerning the implications of this process.

5.1. The Local Legitimization of Public e-Services

The long tradition of developing one-stop government offices, in combination with specific socio-economic conditions, has shaped a belief system based on specific democratic core values in Botkyrka. These core values involve a view on the role of public organizations as prominent: they have a special responsibility in furthering and supporting equality, equity and the common good. It is thus first and foremost the responsibility of the municipality to support the citizen in effectively acquiring the public services they are entitled to. In turn, this is, by the local policymakers and officials, seen to further trust for, and legitimacy of, the municipality. Core values have been expressed through policy strategies which emphasize an available and flexible municipality, as well as a municipality in close proximity to and in a continuous dialogue with the citizen. Furthermore, the practices of the offices, such as flexible face-to-face meetings regarding a variety of public and non-public issues, have been the predominant implementing activities for realizing core values. These practices have been based on a street-level bureaucratic ideal in which public officials are given much discretion in handling a heterogeneous population with different needs and life situations. The local context of newly arrived immigrants and low socio-economic conditions has played a significant role in contributing to the specific belief system which was firmly institutionalized both in rhetoric and in practices, before e-services implementation.

It is evident that practical change in the provision of public information and services has taken place in Botkyrka during the last decade. Ever since the initial implementation, e-services have increased in importance and are, at the end of our analysis, regarded as the main channel for public information and services by the municipal administration, as well as appreciated and used by almost half of the inhabitants. Public e-services are evidently here to stay, whereas one-stop government offices, although still significant, are being downplayed as a supplementary channel. Nevertheless, the rhetoric of central key actors and policy documents shows that the same local democratic core values keep guiding e-service developments, as they earlier on guided the development of one-stop government offices. E-services are regarded as the natural continuation of developing an available, responsive and present municipality and is thus in line with existing ontological beliefs concerning the role of public organizations and the citizen. Several types of communication channels are considered to add value to public service provisions, since it benefits different groups and individuals. Through e-services, more citizens can get easy access to public services and even more special needs be catered to. Public services can become even more flexible and available through non-stop accessibility and personalized Internet portals. The one-stop approach of fast and available services, which began with the one-stop government offices, can thus be further developed with public e-services. The experiences of the offices have consequently structured ideas, discourses and practices of e-services. This is evident in how the aims of the e-services are the same as for the offices and how they are, in some respects, regarded as the same thing. In sum, we argue that the local democratic core values have, been decisive for the implementation process: they provide e-services with meaning for municipal employees and citizens and have legitimized and thus facilitated the process.

The case study shows a combination of continuing along the tested and legitimate path and responding to changing contextual factors. As the increased centrality of e-services and the web-based portal vis-á-vis the one-stop offices indicates, real changes have been implemented. However, these new implementing activities are used to buffer in-depth changes and contribute to a preservation of core values. Thus, local democratic values are here used as a promoter and facilitator of public e-services.

5.2. The Local Definition of Public e-Services

The analysis implies an overarching conclusion of this article - locally defined and institutionalized democratic core values have a fundamental role in how e-services are implemented and why the implementation process looks the way it does. The local autonomy of Swedish municipalities is indeed influential in this respect. Municipalities are able to interpret e-services according to local core values because the formal institutional context of local autonomy allows them to.

The case thus illustrates that the policy of e-services is - to a certain extent - regarded as value neutral by municipal key actors. The local implementation process boils down to the implementation of a technology which is given meaning largely through the existing belief system of the municipality. Although a strong economic rationale, largely based on NPM, is evident in global and national articulations of an e-services policy - and to some extent in the Botkyrka rhetoric - the local rhetoric and practices reveal mainly other driving forces of e-services, namely a locally developed rationale and reasoning. Accordingly, e-services are not necessarily the revolutionary tool that threatens to overturn democratic values of public organizations. In fact, this presumes a rather deterministic perspective in which the role of the existing local institutional setting is discarded, for instance, with regard to the democratic ideal the municipality adheres to. The Botkyrka case illustrates democratic values that partly follow a communitarian view of democracy. This view continues to have a prominent role during the development of e-services. The relationship between democratic values and e-services should thus be seen less in the light of how e-services are defined as policy on a global or national level and more in the light of how local institutional factors in general and core values in particular shape and reshape e-services as a policy. Furthermore, by analyzing the interplay between e-services and core values, we have illustrated the significance of viewing the implementation of e-services as part of a process. E-services are not implemented into a vacuum. This also means viewing change as a process: public e-services are incrementally joined and developed in conjunction with past policy processes.

6. CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

In this article, we have highlighted the need for examining what values and perceptions are being embedded in and realized through the implementation of public e-services. We have approached this aspect by analyzing the relationship between democratic core values within a local public administration and e-government reforms. The following research questions have in turn guided our analysis: (1) How and why are local democratic core values related to the implementation of public e-services? (2) Can local democratic values, crudely put, be seen as a barrier or promoter of public e-services? (3) What are the implications thereof? Our main conclusion is that democratic core values of the studied municipality, Botkyrka in Sweden, in several aspects have acted as a promoter and facilitator of the implementation of public e-services. The Botkyrka case illustrates how certain organizations find a way of fitting new developments to existing policy traditions and belief systems, thus creating and maintaining trust and legitimacy internally (within the organization) and externally (vis-á-vis citizens and other stakeholders). In our case, local core values are used to reinforce e-services but also vice versa; e-services are used for reinforcing local core values. Rather than renegotiating the core values of why e-services are carried out, implementing activities of how to carry out the organization and provision of services are being negotiated with e-service developments. Despite the often economic logic of e-services, the local democratic core values of Botkyrka are still in the foreground when motivating the development of e-services. The specific local institutional setting thus remains prominent in the development process. More generally, the case illustrates how the democratic potential of e-government can also be studied in the context of public e-services.

The conclusions above also touch upon a number of aspects which could have consequences for how public services are carried out and in the long run, for democratic legitimacy. We would like to highlight these in order to point at issues for further research. Through the one-stop government offices, the personal face-to-face meeting has long been an important institution for accommodating several of the democratic core values and policy strategies of the municipality, that is, to meet heterogeneous citizen needs through responsive and flexible public services. In comparison, ICT is often not as flexible but instead tends to follow standardized ways of offering services, where users often are assumed to have similar preconditions. Treating all users the same may increase the risk of exclusion, in particular in a heterogeneous municipality like Botkyrka. This exclusion might be created not because of a lack of technical knowledge as such, but rather as a knowledge gap with regards to the Swedish public institutions, a language problem or a lack of trust in technology. Thus, even though the democratic core values remain strong in the rhetoric of actors, the changing of how services are carried out, i.e. practices, and the view of the citizens as more equal users, might in the end have consequences which could lead to a hollowing out of existing core values. Rhetoric can sometimes influence practice by serving as the yard stick by which activities slowly are adjusted to (Røvik 2000). In other words, regarding citizens as more equal users could in the end lead to the municipal actors increasingly treating them as such, which in the studied socio-economic context could have consequences for the democratic legitimacy of the municipality.

Compared to one-stop government offices, the development of e-services has not been driven to the same extent by the specific needs of the local community. Instead, the actors have adapted to a modernization process, which is not only regarded as inevitable but which also is, for a single municipality, difficult to shape according to local preconditions. Municipalities are usually reliant on existing technical solutions developed by private distributors. Although the municipality rhetorically has managed to fit its core values to developments in e-government, the question for the future is if it will also work in practice. Core values are not only in the rhetoric of local council members and officials but are also expressed through the practices of these actors. Hence, the question for the future is: how important is the personal face-to-face meeting for democratic legitimacy in a local community like Botkyrka? Today's Swedish, and Western societies, have indeed become more culturally and ethnically heterogeneous. This places greater demands on public organizations to handle this increased heterogeneity in order to adhere to the constitutional rights of equity and equality. As stated above, there is multidimensionality in citizenship which is not yet accounted for in public e-service provisions. Thus, public e-services may to a greater extent have to target issues such as citizenship, equality and competences in order to create a legitimate public administration and a truly "responsive" and "citizen oriented" government.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by MSB Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency.