Exploring the use of PPGIS in self-organizing urban development: The case of softGIS in Pacific Beach (California)

- Research Fellow, Department of Real Estate, Planning and Geoinformatics, Aalto University, Finland. Email: kaisa.schmidt-thome@aalto.fi

- Research Fellow

- PhD Candidate

- PhD Candidate

- Associate Professor

INTRODUCTION

Discussing public participation geographic information systems (PPGIS) together with 'self-organizing urban development' is challenging, as the two research fields have different foci. The debates around self-organizing urban development have concentrated on empowerment (Boonstra & Boelens, 2011), agent-based systems (Portugali, 2000) and urban regeneration led by local stakeholders (van Meerkerk, Boonstra, & Edelenbos, 2012). When utilizing technological solutions to support community building, the tools have usually been found within community informatics (Gurstein, 2007; Saad-Sulonen & Horelli, 2010). Public Participation GIS (PPGIS) solutions, in turn, draw on geospatial technologies for collecting and analyzing public, place-based knowledge. They have been developed to expand "spatially-explicit public participation" (Brown, 2013, p. 1) in land use planning as well as natural resource management (Brown & Reed, 2009; Brown, 2012b; Kahila & Kyttä, 2009; McLain et al., 2013). The involved end-users of PPGIS applications have often consisted of government organizations, and this array of users has seldom included community organizations, which in reality, have a central role in the debates around self-organizing urban development (cf. Boonstra & Boelens, 2011) 1 .

The demanding participatory setting described above holds true also for the case at hand, which introduces a PPGIS application called 'softGIS' as a potential facilitator of self-organizing urban development. The softGIS approach, which has been in development since 2005 at Aalto University, Finland, has been advanced in cooperation with urban planners with the aim of improving the user-friendliness of physical settings (Kyttä & Kahila, 2011), by collecting and analyzing large datasets of experiential knowledge from lay people (Kyttä, Broberg, Tzoulas, & Snabb, 2013). The reported study-discussed in this paper-was carried out in mid-2013 in Pacific Beach (PB), San Diego, California and represents the first time softGIS was used in cooperation with a community organization.

In this article we ask the following research questions: Can a PPGIS application facilitate self-organizing urban development? In addition, what prerequisites for sound PPGIS-linked facilitation can be identified in the Pacific Beach case study? In more concrete terms, we study the outcomes for the participating partners and ask which factors appeared to be critical in the implementation of the softGIS study in Pacific Beach. The outcome was quite positive, but a number of observations point to the fact that the process could have ended up rather differently, if we, for instance, had chosen another community organization to start with. In addition, the degree to which the Finnish approach to studying perceived environmental quality would 'travel' successfully to the U.S. remained an open question throughout the research process 2 . The case also brought up a number of technical issues related to the transposition of various technical solutions from one continent to another.

The aim of the article is to describe and analyze the first softGIS study undertaken with a community organization in the context of self-organizing urban development in Pacific Beach, San Diego, and to reflect over the suitability of PPGIS in the fields of community informatics and urban planning. The paper begins with a discussion of the applied theoretical framework used. We then present the Pacific Beach softGIS case study and discuss how it can be linked to the self-organizing urban development process in that community. In the paper's conclusion, we discuss the prerequisites for PPGIS to successfully contribute to self-organizing urban development. We argue that despite having been developed for formal urban planning processes, PPGIS applications can correspond with the ideals commonly set out in the community informatics literature. We also call for a deeper exchange of ideas between the scholarly discussions on PPGIS and community informatics.

POSITIONING PPGIS AND SELF-ORGANIZING URBAN DEVELOPMENT

Self-organizing urban development

We use self-organization in urban development to refer to the initiatives for spatial interventions that originate from civil society via community-based networks (Boonstra & Boelens, 2011). When citizens and other stakeholders are motivated and become engaged in shaping their cities, it is neither necessary nor possible that governments always direct the process. Public sector planners may be entirely absent or merely act as facilitators (ibid.). The adoption of the self-organizing perspective is also a way to distance oneself from the development of formal participatory urban planning methods (Wallin et al., 2012). Why should people merely participate in certain predefined issues, if co-production is also possible? According to Huxley (2013), participation is often used uncritically as a synonym for democratic urban and land-use planning, or as "a given ideal and aim, in which, to a greater or lesser degree, residents as citizens have a right and a duty to take active part in decisions affecting the environment of their local areas" (ibid., p. 1532). Saad-Sulonen (2014) calls this 'staged participation', coming from governmental institutions, which stands in contrast to self-organization, where citizen-led initiatives are recognized. We are not suggesting that (participatory) urban planning should be converted into self-organizing urban development. Rather, we stress the complementary roles of formal planning processes and community-based self-organization (Horelli, 2013; Saad-Sulonen, 2014; Wallin & Horelli, 2010). However, in this article we focus on situations where self-organizing as such suffices to harness the will of the citizens to bring about certain changes in spatial development.

Boonstra and Boelens (2011) claim that community-based self-organization can play a significant role in shaping urban development both in countries with and in those without a strong planning regime. In the US and the UK contexts they mention the business improvement districts (BIDs), which are consortia of property owners and businesses that collectively contribute to the promotion and maintenance of their local district. Although Boonstra and Boelens (2011) stress that BIDs can be successful only when they are strongly embedded locally and there is a shared feeling of urgency as well as reciprocity in relation to investments, they do suggest that the BIDs clearly represent one possible way forward for these communities. Other scholars, however, view BIDs as "encapsulat[ing] the neo-liberalization of the city" (Ward, 2006, p. 55) and are critical of these public-private partnerships whose main priority is business profitability (Cook, 2009). Against this background it is interesting that the community organization at the heart of our study is trying to initiate a partnership which would resemble a BID but would not only include businesses or commercial property owners, but also other property owners and residents. This concept is referred to as a Community Benefit District (CBD). CBDs are often non-profit organizations through which local businesses and community members can empower a single organization to improve the district in ways that the city governments do not cover but that go beyond what is manageable for individuals 3 .

Empowerment tools from community informatics - and beyond

Self-organizing may gain strength through the use of information and communications technologies (ICTs)-and many scholars have acknowledged the use of ICTs, especially social media, as enablers and arenas of the self-organizing movements (Wellman & al., 2003; Wenger & al., 2009). Saad-Sulonen and Horelli (2010, 1) have mapped the broader field of "ICT-mediated citizen participation in urban issues", covering a wide array of fields that utilize technological tools to engage different stakeholders in shaping their cities. Where citizen activism would draw upon tools from e-activism; governance actors drawing upon tools from e-participation; and urban planning praxis drawing upon PPGIS (Public Participation GIS) tools-community development would turn to community informatics tools for ICT-mediation. For example, in their study of a participatory process in Helsinki, Saad-Sulonen and Horelli analyzed the role of chosen community informatics tools in both empowering the participants and achieving a joint design outcome. They concluded that the combination of face-to-face and ICT-mediated methods worked well for the studied collaborative design task; as such methods did in digital citizenship capacity building amongst a youth group. Similar interpretations of successful ICT-mediated community building and empowerment of community organizations are readily available in the literature (Evans-Cowley, 2010; Foth, 2009; Fredricks & Foth, 2013; Wallin, Saad-Sulonen, Amati, & Horelli, 2012.Saad-Sulonen and Horelli (2010) see a close connection between urban planning and geographical information systems (GIS) as well as planning support systems (PSS) including their participatory arms in PPGIS. They characterize existing GIS-related solutions as mostly expert-driven and view this as a hindrance to community development. Community development stresses the enabling and empowering perspective and thus shares an affinity with community informatics which identifies the importance of communities in steering or shaping digital technologies (Gurstein, 2007). While helpful for this overview, the juxtaposition of expert-drivenness and empowerment potential could prove problematic elsewhere. As Saad-Sulonen and Horelli (2010) note, community informatics seeks to introduce information systems that are "able to translate the essence of how the community functions or should function" and thus facilitate self-organizing and the empowerment of the (local) community. Why should these aims not be achievable with the help of PPGIS tools4 ? Although the PPGIS tools have often been developed alongside official planning processes and with the help of advanced software, community organizations may be able to utilize PPGIS solutions on their own. Our case shows how community organizations autonomously employing PPGIS tools can work with only a small supporting effort from local service providers.

PPGIS evolution and the softGIS application

With PPGIS we refer to methods that use geospatial technologies to engage the public in order to integrate place-based knowledge to inform land-use planning and other decision making that has spatial implications (Brown, 2012a) 5. The PPGIS application discussed in this article is called 'softGIS'. The softGIS approach described in this paper involves the pioneering effort of collecting geocoded, experience-based data from the citizens online through the use of map-based questionnaires (Kyttä & Kahila, 2011). Development of this approach first began in 2005 with a thematic emphasis on perceived environmental quality but has since been developed both to improve its applicability in the different stages of the urban planning process (Kahila & Kyttä, 2009) and for better analyzing everyday urban life (Kyttä, Kahila, & Broberg, 2011; Schmidt-Thomé, Haybatollahi, Kyttä, & Korpi, 2013).

Previously, softGIS has primarily been discussed in the context of PPGIS developments (Brown & Kyttä, 2013) or planning support systems (Kahila-Tani, 2013), and has had little, explicitly, to do with the discourses around community informatics (apart from Knudsen & Kahila 2012 discussion of softGIS in the context of VGI, voluntary geographical information). Within the range of PPGIS applications softGIS belongs to those that aim for large and representative datasets, in particular when contributing to various established scholarly discussions, such as perceived environmental quality (Kyttä et al., 2013) or health promotion studies (Broberg, Salminen, & Kyttä, 2013; Kyttä, Broberg, & Kahila, 2012). The rigor displayed in terms of data collection and analysis has two main motivations. On the one hand, the datasets have to meet the requirements of advanced statistical analysis. On the other hand, much of the potential with respect to the softGIS tool is seen to lie in its deliverables for the broader public instead of merely echoing the most active community members (Brown & Kyttä, 2013).

As Brown (2012b) has elaborated, the explosion in internet mapping applications has created a favorable environment for the expansion of PPGIS. However, it seems that technological innovation has not yet come coupled with a proper understanding of human factors and agency barriers-resulting in the suboptimal implementation of PPGIS (ibid.). We will explore this claim further in what follows, and try to bypass the "intellectual tug-of-war" (Brown & Kyttä 2013) between the two dominant components of PPGIS- geographic information systems (GIS) and public participation (PP). We believe that this "uneasy merger of two contrasting knowledge paradigms" (ibid.) may have added to the impression that PPGIS is overly expertise-driven and establishment-serving, making it difficult to open up to or augment work in Community Informatics. It would, however, be detrimental to the broader field of ICT-mediation in urban issues, if this impression were allowed to prevail unchallenged. Thus, our aim is to seek a rapprochement between PPGIS and Community Informatics 6 and, as such, we welcome Saad-Sulonen's (2014; also Horelli, 2013) suggestion of 'combining participations' as a major conceptual step forward in this respect.

Serving the 'civitas'?

We should search for "protocols that actually open up better forms of civility and interaction and new domains of possibility for a wider range of citizens" (Aurigi, 2008, 8). The various fora for dialogue with and among citizens are there to utilize "the power of internet-based communication channels to consolidate existent social aggregations as well as to create new ones" (ibid.) in a context where the actual and the virtual are intertwined. Foth et al. (2011), in turn, talk about urban informatics as an intersection of place, technology and people in urban environments, and explore how dealing with knowledge (collection, classification, storage, retrieval and dissemination) can matter.

The expected contributions from ICT tools range from rather instrumental considerations (e.g. how proper data contribution mechanisms can enhance data accuracy; see e.g. Song & Sun, 2010) to broader themes of community-related concerns (facilitation of self-organizing and empowerment, cf. Saad-Sulonen & Horelli, 2010; Horelli et al, forthcoming) and - even more broadly - working towards civic change through participation (Dunn, 2007). Indeed, numerous expectations have been have been forwarded in this respect. Ganapati (2011) hopes to see "new forms of activism, participatory democracy and neighborhood empowerment" supported by VGI. Pfeffer et al (2010) call for "inclusion, empowerment and accountability in urban development" and "participatory and empowered public action and democratized decision-making" from the use of spatial knowledge digital tools (Pfeffer et al., 2013). Evidence is available of such progress. McCall & Dunn (2013), for instance, have studied the uses of geo-informatics tools against a checklist of good governance, asking if these tools have the potential to support legitimate, respectful, equitable, competent and accountable systems. In practice their study did not cover these five criteria but focused on participation and the recognition of local knowledge. In our case study we will not strictly adhere to the checklist, although we will touch upon some of the listed issues.

AN ILLUSTRATIVE CASE STUDY IN PACIFIC BEACH, CALIFORNIA

Searching for a test case

A research exchange presented an opportunity to test softGIS for the first time with community-based organizations, without any formal connection to publicly employed urban planners or other city officials. In order to find a suitable community organization, the Aalto University research team first considered the case study areas utilized by the other visiting scholars of the same research exchange 7 , but soon decided to instead map the 'organization landscape' of the area that they were living in with their families, namely, the community of Pacific Beach (PB in common parlance).

Pacific Beach is a part of San Diego, California. In broad terms, it covers the area between the Pacific Ocean and the highway I-5, with La Jolla to the North and Ocean Beach to the South. In the light of the census data 8, the population of roughly 40 000 person community is mainly white (87%) and English-speaking (84% speaking only English) with the largest five-year age cohort being 25-29 year old men. In Pacific Beach 29% of the population lives in detached single family units, which is far less than in San Diego region in general (47%). For potential visitors the San Diego Tourism Authority describes the area as "the iconic Southern California beach town" and as "a favorite spot amongst college students and young adults living the California Dream". Pacific Beach is a popular destination for both one-day visits and longer vacations, and quickly becomes crowded during the most important holiday weekends. The websites 9 of the local administration and the press, in turn, tell us about an ordinary neighborhood where most people wake up early to go to work or school.

When searching for a community organization representing broad community interests, there appeared to be two main candidates, the 'PB Town Council' and the newly established 'Beautiful PB'. The purpose of the former non-profit organization is to provide a discussion forum and to communicate the views of the community in the direction of governmental agencies - and to take other action on issues considered important. The recently formed, Beautiful PB, describes itself as "a group of active Pacific Beach residents, business and property owners working collaboratively to improve the environment of our southern California beach community". Formally it is a registered non-profit organization with five board members representing actors considered important in fostering the aims of Beautiful PB. Although Beautiful PB is a newcomer among the community organizations, it has an ambitious agenda - it has argued that a sustainable community master plan should be created10 , which indirectly implies at least a modification of the existing Community Plan (from 1995). Later we discovered that one reason for the establishment of this new organization was the fact that none of the existing organizations were in the position to initiate a Community Benefit District (CBD) in Pacific Beach.

Another candidate organization was the 'PB Planning Group', which has the mandate to make recommendations to governmental agencies on land use matters. It is voluntarily created and maintained by members of the community. A final candidate could also have been the Business Improvement District (BID) of the area. The BID called 'Discover Pacific Beach', in operation since 1997, is a registered company with 1300 business members from Pacific Beach and neighboring Mission Beach. At the scoping stage of our study in early 2013 we were not aware of the 'Save PB' group, which had been established in 2005, to deal with neighborhood issues, in particular, with the nuisance associated with the party scene and alcohol consumption in Pacific Beach.

Process of the Pacific Beach softGIS study

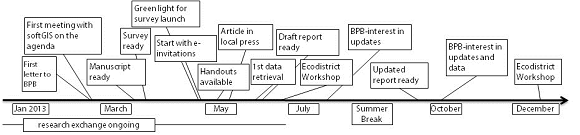

We chose to address Beautiful PB first as it had articulated an interest in improving the built environment of the community. Our first e-mail to Beautiful PB members in late February 2013 proved to be decisive, as the feedback was positive from the start. The community organization was interested in hosting us for testing the softGIS application in Pacific Beach. The Aalto University researchers were welcomed by the organization, and the survey-related issues found a firm place on the agenda of their regular meetings11 . From initially being the final point to be dealt with, time permitting, at their meetings, the softGIS survey gradually rose up their list of priorities. Considering that our offer to introduce PPGIS in Pacific Beach came out of the blue, the organization quickly agreed on cooperating with the research team. However, the preparatory phase turned out to be long (see Figure 1): revising the questionnaire and related guidelines took longer than initially expected due in the main to the fact that the board members, who had agreed to review the survey manuscript in order to adapt it to local circumstances, were all volunteer staffers.

Having finally got the go-ahead (on 6th May 2013, in the Beautiful PB meeting) the researchers proceeded quickly to launch the survey 12 in cooperation with Beautiful PB. As there was no true budget for carrying out the survey, it was not possible to take a sample of the population and to address people by mail with invitations to respond to the internet-based questionnaire. The only option was to spread the message in the area. Important community organizations were listed and contacted via e-mail with a request to inform their members. Small invitation cards were printed and brought to key meetings and events. The local press was contacted and informed comprehensively about the project and its background, which yielded results on the 23rd of May, as the survey invitation appeared on the first page of the Beach & Bay Press.

Some of the potential key distributors of our survey invitation took quite a while to include the invitation in their regular newsletters. When, for instance, the 'Friends of Pacific Beach Secondary Schools' proceeded with their newsletter, it was already time to begin the initial analyses based on the data gathered up to that point, so that the information could be fed into the final workshop of the research exchange. It was thus agreed with Beautiful PB that the data collection stage could continue beyond the original cut-off point and that a new round of analysis would be carried out as soon as the number of respondents was judged to be significant.

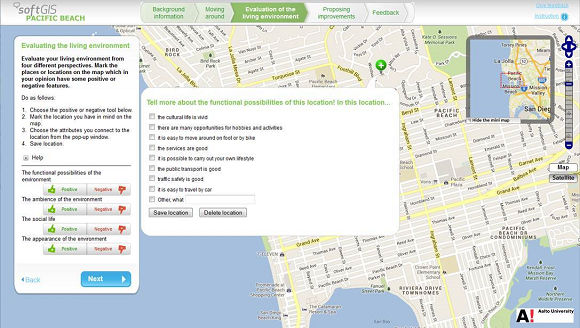

The Pacific Beach softGIS survey was divided into four main parts. The first part consisted of questions concerning background information, including a page where the respondents were invited to locate their current residence on the map. In the second part they were asked to mark the places they tended to visit in their everyday lives as well as the routes they considered important. In the third part, it was possible to evaluate the environmental quality as perceived by the respondents. They were asked to mark positive and negative attributes on the map, following four predefined perspectives with sub-categories13 . Then they were asked to give an overall estimate by utilizing a slider (moving along the scale from very bad to very good). In the fourth and final part of the survey, it was possible to suggest local improvement proposals by marking possible measures on the map. The survey also included several fields for open feedback in case the respondent wanted to be more precise or otherwise complement the response.

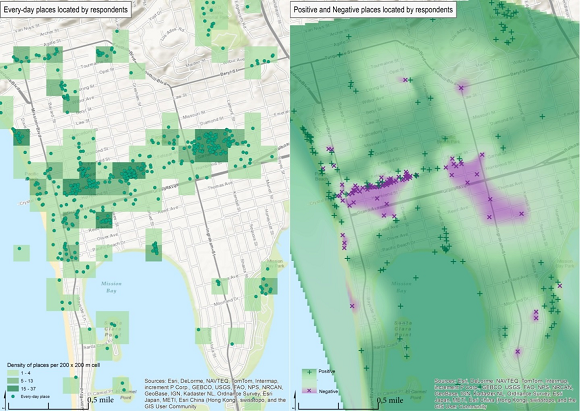

In order to be able to produce the first set of maps in early June, the data collected up until then was retrieved from the server on June 3rd. One researcher, located in Finland, began the spatial analysis while others locally situated continued their efforts to solicit further respondents to the survey. The draft summary included a set of maps and an accompanying analysis about Pacific Beach as a living environment. Selected comments from the open feedback forms of the questionnaire were included to give examples of both the content addressed and the attitudes of respondents. The draft summary report was available on June 8th and was forwarded to the Beautiful PB. On June 9th the Chairman had already worked through it and sent it to the other board members with his interpretations (an issue that will be returned to in the next sub-section).

Despite the still rather low number of respondents at that stage14 , many of the salient issues pertaining to the area could already be clearly discerned. The centrality of Garnet Avenue as the main commercial district and everyday hub of the community was obvious-but so was its problematic nature as the feedback suggested. It was also clear that many people wanted this important commercial and community zone to be upgraded. Another key message was that few if any parks and beach sections were criticized at all, and the same also applied to the majority of the residential areas in the study.

By June 12th the number of respondents had risen to 221, and it was decided to repeat the analysis with the new dataset. Approximately 155 respondents provided more or less full background information and responded to most parts of the questionnaire. During the summer months the report was updated, though it did not have to be fully rewritten: the picture remained pretty much the same. The report included sections on data collection, respondents' background variables, overall perceived environmental quality, positive and negative hotspots, residents' everyday networks (routes and most frequented places, according to various sub-categories) and proposed improvements (also according to various sub-categories). As a summarizing statement it was noted that:

"There is a clear tension between PB being both an ordinary town where people wake up early to go to work or school, and PB as a beach community attracting party makers. In concrete physical settings these perspectives have to be reconciled both along the main service/business axis of Garnet Avenue and the ocean front walk."

The report was finalized on 23rd September with Beautiful PB making it available online on 7th October 15 .

Besides learning from the constellation of trying out softGIS with a community organization for the first time, the research team had also to take note of other, more technical issues with respect to the study. In anticipation of future projects, the Pacific Beach study provided an opportunity to identify risks and to avoid costly mistakes by doing them first 'for free' on a smaller scale. Technical issues (e.g. internet browsers accomplishing the required tasks) seemed rather unproblematic16 , while the general amount of responses matched initial expectations. The cooperation between the softGIS home base (located in Finland) and the researchers located in the case study area also worked well despite the 10-hour time difference17 . The questionnaire was criticized primarily for being too long. The potential outreach of the survey with respect to its ability to handle different language groups was not tested in Pacific Beach, which is primarily English-speaking. In most other parts of San Diego, however, it would not have been feasible to launch the study only in English.

Outcomes relating to the community organization

Having received the summary report, the board members of Beautiful PB reviewed the results and discussed them among themselves in June, although the Chairman also forwarded his interpretations when the researchers asked for feedback. He had concluded to the other board members that the findings of the summary report seemed "to confirm our current focus on the areas of oceanfront, Mission Bay Gateway and business district". In the same e-mail he also noted that "the summary seems to be right. I think it is possible to preserve the things people like about the Garnet business district and make it better". Clearly the survey results gave substantial backing to the board members' intentions. For instance, the identified hotspots (i.e. where negatively perceived quality and high frequentation by the residents coincided) matched their views about possible intervention measures. The survey made it clear that concrete action was necessary in the same places, where the board had envisioned interventions.

One of the aims of the Beautiful PB was to be, in the not too distant future, the midwife to a new organization, the Community Benefit District. In order to inform citizens of this possible development model and to attract keen protagonists to the endeavor, Beautiful PB has tried to access grants to introduce 'model blocks'. Indeed, the summary report of the softGIS survey has already been utilized in these model block considerations with the board reviewing which areas were the most suitable showcases for possible larger future investments and other arrangements.

Besides the CBD considerations, the material (both the summary report by the research team and the raw data) is also being utilized in the initiation phase of a PB-based 'eco-district' as it is currently promoted by the American Institute of Architects, San Diego. Some Beautiful PB board members are active in both the CBD and the eco-district preparations, thus creating a direct link in terms of the utilization of the softGIS results. The first opportunity of this kind was to compare the survey results with the inputs gathered from the residents during the first Town Hall meeting, which launched the public eco-district preparation efforts on June 29th. There it was also made known that the Sustainable Design Assessment Team (SDAT) will offer supervision to the community. While preparing for further meetings associated with the eco-district 19 , Beautiful PB signaled to the research team that a further update of the summary report would be very welcome, as well as access to the raw data gathered by the survey. Later we were told by the Beautiful PB chairman, that (besides putting the report on their website) they had also presented the report at several public meetings (Planning Group, Town Council etc.) in October and November, to attract people to their December events.

One of the key problems here, however, is that the established residents' perspective dominates the survey. As the 'average person' taking the survey was a 46-year old woman who is working and whose household had on average, 2.2 cars-suggesting that the survey had not attracted many responses from the biggest population cohort of young men (cf. census data in the first sub-chapter on the case). Beautiful PB has been trying to change this by starting a campaign to get the younger generations to respond to the survey. The research team promised to have a new look at the data, if a significant number of new respondents could be attracted. Besides the direct e-mail feedback 20, this commitment to search for supplementary respondents is also a tacit acknowledgement that Beautiful PB has benefited from the cooperation with Aalto University.

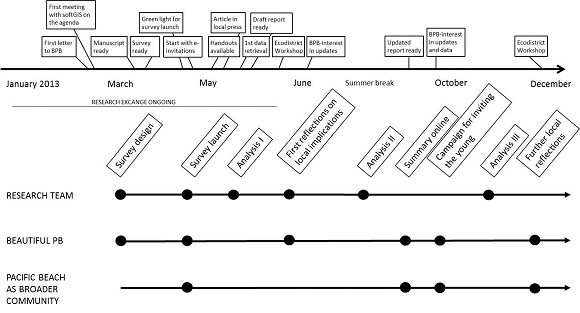

We have come to know the self-organization of Pacific Beach mostly through the cooperation enacted with Beautiful PB. With this in mind it would be useful to attempt to separate the various phases of the survey process in accordance with which groups took part in the study (Fig. 4). The survey design and analysis phases primarily concerned the research team only-however, when reflecting on the local implications of the survey results, Beautiful PB clearly played a major role. The survey launch and later campaigns to invite people to participate were phases which were experienced across the broader community, as was the phase when the results were put online and discussed in connection with the eco-district intentions. It was something of a happy coincidence that the survey themes matched these considerations in the end. If the gathered knowledge continues to travel well, along with the CBD intentions and the eco-district process, the future updates to the current Community Plan are also likely to be informed - to some extent at least - by the survey conducted in 2013.

The SoftGIS tool in the context of self-organizing urban development

We can see that the softGIS study played three main roles in the self-organizing urban development of Pacific Beach. With 'self-organizing' we are referring to the existing, self-contained local activism designed to improve the neighborhood.

The first role was simply to be a tool among others, facilitating a particular 'move' in the organization landscape of the area. The survey being of a certain kind, its profile added to the impression people already had about the recently established Beautiful PB. It also provided Beautiful PB with an opportunity to inform the broader community about its existence and a chance for the established organizations to react and to adopt a stance towards the action of the newcomers. In this light we witnessed the reaction of SavePB, which was introduced to us as the local Neighborhood Watch group. The contact person of SavePB was contacted in order to gain access to the largest e-mail list available of Pacific Beach residents, but she refused to forward the softGIS survey to the list21 in spite of the efforts made by Beautiful PB and the researchers. This was very unfortunate in terms of data coverage, but it also provided Beautiful PB with an opportunity to show a previously existing organization (SavePB) that it was an important new player that would, in future, have to be taken seriously.

The second role played by the study was to be a catalyst in a process where the residents' perspectives had gradually been gaining ground within the self-organizing approaches of local groups. The softGIS survey was therefore available at the point where the community had a demand to understand itself beyond the business owners' perspectives that, traditionally, held a strong position due to the position held by the existing Business Improvement District. The survey seemed to tap into a local desire on the part of the residents to finally 'have their say'. Previous efforts of this kind, advanced by SavePB, had decreased after SavePB managed to force through the prohibition of alcohol consumption on the local beaches, with the focus increasingly now on the security of the residential areas. As such, there was clearly room for new initiatives such as those proposed by Beautiful PB which the PPGIS application happened to complement. The rather over-enthusiastic journalist, who had taken the story about the survey on board, e-mailed the research team after he had heard of the intention to use the survey results for discussing the future of Pacific Beach as a sustainable community or eco-district: "This is something that has needed to be done, and you are the driving force now behind something that could change the very future of Pacific Beach!"

Based on the above, as well as on the various BeautifulPB meetings attended, it can be inferred that a survey addressing the residents appeared to complement the self-organizing tendencies in Pacific Beach. The parallel grant which enabled the eco-district preparations (supported by SDAT, Sustainable Design Assessment Team) in the area to take place undoubtedly played a bigger role with its clear commitment to listen to the community. With regard to this one of the Beautiful PB board members wrote to Aalto team in an e-mail, in July 2013: "The mapping will be of great service to the SDAT who was here last week on a preliminary visit, preparing for the entire team visit in the fall. They were very interested in the results."

This citation brings us to the third identified role. In Pacific Beach PPGIS was a provider of legitimacy for those community organizations aiming at concrete interventions in the physical environment. In particular, the spatial analysis of the perceived environmental quality provided substantial backing material supporting the choice of interventions prepared by Beautiful PB. For a small newcomer in the organization landscape, the ability to talk on behalf of hundreds of survey respondents was also clearly welcome.

In our attempt to relate these three roles to the broader aim of "augmenting civitas" with spatial data tools (De Cindio et al., 2008), we remain hopeful but wary of the obstacles still to be dealt with. As such, we were careful not to load the introduction of any ICT-mediated tools with unrealistically high expectations in terms of empowerment (see next section), but rather chose to focus on: the interplay of the virtual and social networks (cf. De Cindio et al., 2008); on the appropriate choices from an "ecology of [digital] tools" (Wallin et al., 2010); and, finally, on applying the PPGIS tools "in a sensitive and modest way" (McCall & Dunn 2012, 93). In the end, it is the community that makes the most crucial decisions and in our case the PPGIS application simply found fertile ground. The driver behind the interest in the Aalto research efforts in Pacific Beach appeared to be a willingness to promote participation and good governance (McCall & Dunn 2012, 93). A common interest in improving the everyday living environment took care of the rest.

Identified limitations of softGIS: both potential and actual

With respect to the interplay between community organizations, we identified a number of control and ownership issues concerning the implementation of PPGIS that were critical (cf. Dunn, 2007; McCall & Dunn 2012). If the research team had tried to run the survey on its own, in order to simply test the technical applicability of the survey with a small number of respondents, it would have been feasible but still problematic. We would have inconvenienced people with a comprehensive survey that may have had no local repercussions because its recommendations would never have been put into effect. On the other hand, the cooperation efforts with Beautiful PB meant that it was up to the community organization to decide how to handle much of the process and, above all, how to deal with the study results and their possible implications. According to Brown (2012b), PPGIS represents for many non-governmental organizations something of a 'wild card', as they may have less control over the outcome than when they manage a process, where they can define what counts as public opinion. Beautiful PB did not appear to be afraid of getting the 'wrong' result, but was instead very open throughout the process, which the researchers observed at first hand, particularly during the preparations for the June Town Hall meeting.

Another ownership issue related to the role of the local press. Once the local weekly newspaper had been convinced to publish the survey invitation in late May, many other avenues with respect to spreading the message about the survey suddenly opened up. After people had seen the news, many became more receptive to the invitation than they had initially been. The appearance of the story of the survey in the newspaper probably also opened some gates that would otherwise have remained closed. For instance, the agreement by the Friends of Pacific Beach Secondary Schools to include the survey in the newsletter sent to parents at the end of May was obtained only after it appeared in the newspaper.

The fact that the spatial analysis contained in the survey tapped directly into the core of the previously identified important local issues also represented something of a threat to the process as a whole, since old cleavage lines could have been activated and the study could have been sidetracked or silenced in order to avoid conflict (cf. Dunn, 2007). In the current case, however, this appears not to have been a serious threat. Nevertheless, this situation may change, if the active Beautiful PB members, or the eco-district protagonists, start to employ the data themselves22 as indeed they have already anticipated. The open feedback fields of the survey, for instance, attracted a great deal of constructive comment, but they also saw some very negative statements made about the issues that respondents consider problematic in the area. Disseminating this material more widely throughout the community may however generate unnecessary polarization.

As Beautiful PB, was the only community organization with direct access to the results it was in the position of being able to filter them in such a way that met its own advocacy requirements. It showed no indication, however, of having done this in the communications we observed. A skeptic could perhaps note that it did not have to be selective, as the results actually supported its agenda without need for 'filtering'. In any case, it is hard to see why the organization would have sought the need to misuse the advantage it had in respect of being closest to the information source. The community organization appears to know its own area rather well and has really tried to generate a positive narrative in terms of increasing livability and sustainability. It seems that even the BID-related development model (Community Benefit District) might be in good hands despite the critique of the (neoliberal) model often advanced in the literature (Ward, 2006; Cook, 2009).

Returning to the association of PPGIS with expert-driven systems (see Introduction), it is obvious that Beautiful PB is not, strictly speaking, a layman-based community organization. There are several urban development experts in this community organization, who are able and willing to interface with the broader professional communities such as the SDAT. During our study this expertise existed in parallel with a PPGIS tool that has a long development history both in terms of public participation and GIS (cf. the tug-of-war coined by Brown and Kyttä, 2013). Therefore, it is not easy to simply repeat this kind of experiment in communities with less skilled and organized residents. However, the development of softGIS has clearly been enhanced by taking further steps in the direction to facilitate citizen activism. A new 'do-it-yourself' toolkit, launched in 2012, is aimed at users who seldom have had the opportunity to engage with the techniques used by planning experts or their university partners. This web-based PPGIS 23 service allows lay publics, even those without coding skills, to create their own PPGIS survey, collect data, use the online analysis tools and download data to various programs for further analysis.

CONCLUSION: PPGIS IN SELF-ORGANIZING URBAN DEVELOPMENT

The purpose of this article has been to conceptualize the role of PPGIS in the fields of community informatics and urban development. We have shown that the use of a PPGIS application with a community organization can facilitate the self-organization of urban development. We identified the following kinds of facilitations that augment civitas. Firstly, the introduction of a SoftGIS survey can be a suitable method to enhance the interplay of community organizations. Secondly, the SoftGIS can also legitimize a process in which the community organization initiates concrete interventions to the physical environment. We have not, however, tried to evaluate the larger issue of empowerment in Pacific Beach. However, we assume that the self-organization of Pacific Beach, supported by the Beautiful PB, represents the kind of activism that Paulos et al. (2009) as well as Innes and Booher (2010) have found to be an essential driver of social and spatial transformation.

In addition to the role of PPGIS described above, we identified a number of prerequisites for viable facilitation of this tool in relation to self-organizing urban planning. The first prerequisite of feasible facilitation was the shared field of interest of the key groups that were working with the built environment, environmental quality and the localization of possible interventions. The second prerequisite was that the spatial analysis matched sufficiently well with the understanding that the community organization had of the development options in the area. What mattered also was the long-term interest embedded in the softGIS applications to reliably measure perceived environmental quality for urban planning purposes.

The softGIS study contributed to a local self-organizing process despite the fact that the approach has been developed in close connection with formal urban planning processes. In our view, the fact that this was the case was specifically because of such connections and not despite of them. The built-in expertise of softGIS in relation to issues of built environment did matter, because the intended path of the self-organizing development in Pacific Beach was rather ambitious, aiming at local interventions usually initiated by the formal planning apparatus.

As the case shows, PPGIS can work relatively well in the hands of a community-based organization, at least when it is supported by service providers. However, the case study shared the problematic offset of many studies on ICT-mediated urban issues. As its initial focus was on testing a specific technology with an interested partner, it did not start from the actual needs of community organizations or from those of the broader community. Whether PPGIS was a better solution in Pacific Beach than other potential ICT-based tools, thus remains something of an open question.

ENDNOTES

1 We do not follow Sieber's (2006) notion here

of 'PPGIS' as a conceptual umbrella which would also

include 'PGIS', the participatory solutions often

utilized by grass-root organizations, usually in

developing countries. As Sieber (2006) and Brown (2012b)

note, PGIS applications have been developed with the

goals of non-governmental, community-based organizations

in mind, whereas PPGIS often refers to government

agencies' efforts to effectively expand public

participation. Brown and Kyttä (2013, Table 3) list

further basic differences (not only between PPGIS and

PGIS but also in relation to VGI, Voluntary Geographic

Information) that support our conceptual choice. In our

case, we are dealing with an urban setting of the

developed world, where it made sense to prioritize data

quality and to collect data in the digital form from

individuals (instead of prioritizing empowerment

processes and organizing the data collection through a

series of participatory workshops, for instance).

2 Over the years, softGIS development projects

have been carried out with Finnish, Australian, Japanese,

Portuguese and US based cities and universities. The

projects have also included individual researchers from

Poland, Brazil and Iran.

3Common CBD activities include cleaning,

signposting and other beautification measures concerning

the street scene as well as event organization and joint

marketing.

4 The PGIS applications have already shown

clear empowerment potential in smaller (often rural)

communities of the Global South (Brown & Kyttä,

2013).

5 With this definition we exclude the

discussion which focuses on improving direct public

access to GIS data sources analyses, which some scholars

(e.g. Elwood, 2011 in SAGE handbook) also include in

PPGIS. See also footnote 1.

6This would also entail a rapprochement of

PPGIS and PGIS towards a joint toolbox. PPGIS would catch

up in terms of empowerment potential and PGIS in

technological efficiency, making it possible to engage

the public of large urban settings without laborious

attempt to involve the community in its totality.

7CLUDs (Commercial Local Urban Districts),

supported by the European Community under the Marie Curie

IRSES Action of the 7th Framework Programme.

http://www.cluds-7fp.unirc.it/

8Data from year 2000, although some key

figures from the 2010 U.S. Census have by now been made

available by SANDAG at

http://profilewarehouse.sandag.org/

9For instance PB Town Council

http://www.pbtowncouncil.org/ and the Beach & Bay

Press http://www.sdnews.com/pages/home?site=bbp

10 http://beautifulpb.com/

11 One of the researchers attended most of the

meetings during the research exchange; the team leader

also joined in once. A third team member supported the

survey launch in Pacific Beach, and a fourth one carried

out the GIS analysis in Finland in dialogue with the

researchers on site. For additional information from the

Audit trail of the case study, contact the first

author.

12 http://www.softgis.fi/pacificbeach

13 The sub-categories are a modification of

the PREQ (Perceived Residential Environmental Quality)

scale (Bonaiuto, Fornara, & Bonnes, 2003). The four

main themes included in the scale are (1) functional

possibilities, (2) social life, (3) appearance, and (4)

atmosphere of the environment.

14 Of the around one hundred respondents

approximately 80 had provided comprehensive responses.

This could be anticipated, as the survey was made very

comprehensive in order to test as many sections as

possible. A thorough response must have taken 20 to 60

minutes of respondent's time.

15

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.722626137754793.1073741847.570748036275938&type=3

16 Some exceptions did apply. This time the

newest version of Internet Explorer did not show the

sliders properly but opened an open feedback field

instead. Judging from the data, this may have confused

some five to ten respondents.

17 Having at least one local 'agent' from the

research team in the area was absolutely vital in terms

of initiating and accompanying the survey process, as

well as with respect to gathering knowledge about the

area concerned in relation to the analysis phase.

18

http://beautifulpb.com/projects/sustainable-communities/

19 Such as the event when the SDAT

(Sustainable Design Assessment Team) of the American

Institute of Architects comes to the area "to listen to

the community, work with local stakeholders and assess

opportunities for implementing community projects" in

December.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=738311676186239&set=a.721570247860382.1073741846.570748036275938&type=1&theater

20 Including the Chairman's comment in

September after having read the revised report: "I

appreciate all the work [the research team] did on this

and I think it is very helpful for us".

21 The reasons here had to do with "context

and timing". The contact person knew about the

CBD-intentions and thought the survey would solely serve

that purpose. She anticipated confused enquiries from the

members and invited Beautiful PB to their meeting to

explain things in a little more detail. After the

research team informed her of the broader picture, she

promised to consider sending the survey invitation when

informing the members about the new Beautiful PB website,

which was supposed to be ready soon thereafter.

22 Most of the data was pre-organized and sent

to Beautiful PB in early 2014.

23 The service is provided by Mapita, a

spin-off company of the softGIS team at Aalto University.

A demo version of the Maptionnaire tool is available at:

http://maptionnaire.com/en/. It can be used for free when

addressing small audiences.