Neighborhood Planning of Technology: Physical Meets Digital City from the Bottom-Up with Aging Payphones

- Postdoctoral Researcher, UC Berkeley School of Information, USA. Email: bgs@benjaminstokes.net

- Associate Professor of Communication, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, University of Southern California

- PhD Candidate, School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California

- Director, KAOS Networks and Art Studio

TOWARD DEEP ENGAGEMENT

The future of local communities may depend on their ability to plan their own technology, not just create content. As digital technologies permeate civic life and public space, the tension between top-down engineering and local participation is bringing planning and technology together. For local empowerment, participatory approaches continue to gain traction in both planning and technology design (Gurstein, 2007; Horelli, 2013; Simonsen & Robertson, 2012). Community informatics is poised to go beyond providing tools and to begin guiding urban planning at the process level, especially for the planning of technologies that are a part of shared physical space.

Prior work with informatics has largely sought to improve planning that is relatively top-down (Saad-Sulonen, 2013). The 'participatory' focus tends to center on making planning more participatory, largely neglecting the contributions of community informatics to participatory design (Bilandzic & Venable, 2011; Carroll & Rosson, 2007; DiSalvo, Clement, & Pipek, 2013). In participatory planning, the technology is often fixed and research investigates more participatory use in planning, including online message boards, social media (Evans-Cowley, 2010; Hanzl, 2007), and even immersive virtual worlds (Gordon, Schirra, & Hollander, 2011). Yet even in the case of e-planning, the technology dimension rarely emerges from the practices of participatory design (Saad-Sulonen, 2013).

Why not more mixing of planning and technology design? For reasons we will describe, the interaction can be like mixing oil and water - even when each is trying to be 'participatory'. One immediate barrier is a lack of technology literacy in planning. Few planning participants have the savvy to know what portions of a public technology can realistically be changed, let alone the skills to coordinate a technical process. However, we believe it is possible to combine the participatory practices of planning and design; in fact, an emulsion of the two fields could be empowering and deepen participation. The central challenge may be how to sustain the mix beyond special events (such as 'hackathons').

Reframing Success

Carefully reframing success is non-trivial, and one goal of this paper is to propose a useful frame for the field. Not all technologies are suitable for planning, nor all planning modes. When the goal is to improve the design process and affect the category of outcomes, framing is especially important. We therefore propose to constrain how the two disciplines overlap, and force them into a specific kind of conversation. The overlap of digital and physical is a particularly fruitful area for applying community informatics toward bottom-up planning. Our constraints are:

GOAL OF A JOINT OUTCOME: To insist on the intersection, we constrain what kind of product is acceptable: part technology and part urban plan. The result is to create in urban space a "socially-embedded design." The form itself is flexible - anything from a wired bus stop, to a localized payphone or an interactive storefront. In general, the designs are part physical - what has been called "urban furniture" (Rubegni et al., 2008). The design ties to the neighborhood beyond geo-coordinates, seeking to more deeply address the social dynamics of space and community. Socially-embedding is often easiest in public space, where neighbors and strangers are pushed to interact. The goal is to push beyond basic compatibility with the built environment, and to begin actively shaping the collective experience to some degree. Of course, any urban technological design must account for the "messy human situations" of that space (Bilandzic & Venable, 2011; Pries-Heje, Baskerville, & Venable, 2007). However, social-embedding is a deliberate stance toward the technology as part of the neighborhood fabric. When the neighborhood and technology are one socio-technical system, the technology's future is subject to urban planning.

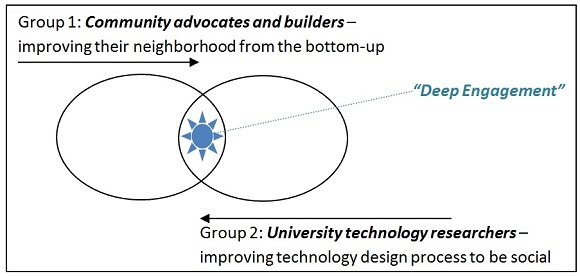

JOINT PROCESS: To maximize the intersection, we constrain the process to be one that strives for "deep engagement." Specifically, this kind of engagement seeks to be simultaneously "doing planning" and "doing technology design." Doing is emphasized in order to stay focused on real communities of practice and activities. Doing aligns with a broad and useful notion of urban planning as a "social project whose task is to manage our coexistence in the shared spaces of cities and neighbourhoods..." (Sandercock, 2004, p. 134). The 'deep' part goes beyond combining disciplines, recognizing that each field has its own depth. Shallow overlap is the danger, and shallow combinations are all-too-common without extra effort. Deep engagement is thus more of a disposition than a checklist - it is the constant effort to alternate between each discipline's ways of legitimizing the process, and offering participants ways to contribute to a community plan and to a technology design.

How can socio-technical systems be planned, not just engineered? Current models have not sufficiently theorized "engagement" for technology planning, including civic hackathons (for an introduction, see Baraniuk, 2013) and community meetings, especially to address the digital divide. Alternatives are needed to build theory. Our research questions include: "How can communities jointly plan and design technology? How can participatory approaches in planning be combined with participatory methods in technology design? Can the user-centered approaches of design be combined with the group-centered negotiations of planning? Can a community-embedded process be sustained beyond short-term hackathons and planning meetings?"

Case overview

This article seeks to develop a method for participatory planning with socio-technical systems. The emphasis is on identifying the "social scaffolds" to sustain engagement and to structure participation, especially across the digital divide.

Focusing on payphones (including 14 purchased on eBay - see Figure 1), this article follows a six-month design process in the historic African-American neighborhood of Leimert Park in Los Angeles, California. Data was collected using dozens of interviews and hundreds of hours of participant observation. Rather than test a narrow hypothesis, this article aligns with grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 2012), and specifically seeks to build theory about the social conditions needed to combine urban planning with participatory design.

During the first several months of the project, participants launched a bottom-up collaborative for their designs called the Leimert Phone Company. From this collaborative, three payphone plans emerged, each re-imagining the telephone for neighborhood social goals, specifically:

- The "Transmedia Storytelling" group focused on ways to distribute historical or personal stories around the neighborhood while directing participants to local businesses with discoverable coupons.

- The "Dial-A-Track" group envisioned new forms of distributing local music through the payphone portal.

- The "Art Buzz" group sought to publicize or help visitors navigate to local art galleries and exhibition spaces -- see Figure 2 for its totem pole visuals, extending a history of what has been called "art by telephone" (de Souza e Silva, 2004).

Beyond individual designs, the umbrella process was valuable for the community to reframe the payphone "problem," and then to build neighborhood support for localizing payphone design.

Beginning with payphones, this study proposes a methodology for the "social scaffolding" to sustain socially-embedded design. Early findings show potential on several fronts, including: (a) civic engagement where socio-technical systems meet; (b) shifts in power relations for the technology and neighborhood design process; and (c) addressing neighborhood economic development by deepening regional distinctions.

Taken together, the deeper opportunity may be how the methodology can unite constituents in defining the problem and building social capital for multiple technology solutions (following agonistic design per Björgvinsson, Ehn, & Hillgren, 2012; DiSalvo, 2010), rather than to "solve" the problem for any one social need. Without this special care, technology design tends to identify a single "best" prototype; by contrast, agonistic design can help sustain the pluralism that is necessary in planning and civic life. These findings will be discussed in detail at the end of the paper.

WHAT EXACTLY IS BROKEN: PAYPHONE OR CIVIC ENGAGEMENT?

Increasingly, new technologies - especially basic pervasive and ubiquitous technologies (Satyanarayanan, 2001) are blurring the target of traditional planning with informatics, as physical space overlaps with digital flows (Castells, Fernandez-Ardevol, Qiu, & Sey, 2006; Ling & Campbell, 2009).

Consider payphones: they are part of public space, can be part of the neighborhood culture, but they are also clearly a technology. In the United States, fewer than 500,000 are presumed to be in use today1 , although cities like New York City are still reported to have at least 10,000 (Albanesius, 2012). From a single-use lens, current payphones can be reductively understood as kiosks, much like ATMs and gas station islands. Yet their future might only incidentally concern telephony; instead, like smartphones they may end up serving many other functions, from video to maps for cultural navigation, from web browsers to being community storytelling tools. Thus the word 'phone' is misleading (given its Greek roots as "distant voice"). In an increasingly mobile world, there is distinct value in how phone booths create a bridge from online flows to reliable physical coordinates in public space.

One barrier to planning for the future of payphones is a limited public understanding. Failing to understand the consequences of a technology (like payphones) is akin to suppressing the public's right to form, discuss and mobilize. In the language of John Dewey, publics form in response to everyday life and its problems (1927), so a failure to understand the problem prevents adequate public debate. Fortunately, the very blight of aging payphones can be a hidden blessing, since problematic technologies in urban space can actually spur the community to respond (DiSalvo, 2009; Marres, 2005) and collectively diagnose the problem.

To investigate payphone redesign from a bottom-up engagement perspective, we begin with a single (problematic) payphone.

A Broken Payphone: an opening in Leimert Park

In historic Leimert Park, it was a broken payphone that started the design process from the bottom up (see Figure 3 below). Local business owner Ben Caldwell asked: "If I own the wires that run to that phone, what can be done with it? Right now it attracts vandalism, and hurts the neighborhood." This framing was essential to opening the door; it named the problem, and advanced the problem-solving drive that is at the heart of both planning and technology design.

More specifically, Caldwell has raised the question of access in a way that pairs technical access (electrical wires) with issues of public space (sidewalk vandalism). His framing pushes beyond immediate users of the technology (payphone users) to consider the effect on the community, and to prioritize the consideration of unintended consequences like vandalism. Issues like vandalism are what are called "neighborhood effects" that go beyond any one business, much like studies of social capital and its ties to crime and economic development (e.g., see Sampson, 2012). In other words, Caldwell's phrasing demands the mutual consideration of planning and technology that we call "deep engagement," and points to solutions that are socially embedded to address the neighborhood fabric.

The history of this specific payphone is also telling: it rests on an ornate stand where it was installed in 1995 and initially drew more than $500 a month in quarters. But for the seven years prior to this case study it had been non-functional, ever since the private owner fell ill and his family rejected the declining business as not worth the trouble. Unused, the booth took up space, gathered graffiti and a smell of urine. Caldwell is a longtime artist whose storefront business KAOS Networks serves as a community space for multimedia arts in Leimert Park, just across from the main square.

If planning is bottom-up, the point of departure must be a specific neighborhood. Leimert Park is a small Los Angeles neighborhood (1.19 square miles) with one of the largest concentrations of African-Americans (79.6%) in the city.2 As a cultural hub, the neighborhood stands out as a beacon for African-American culture and arts -- home at various points to Ella Fitzgerald, Ray Charles and former Mayor Tom Bradley (Exum & Guiza-Leimert, 2012, p. 9). Filmmaker John Singleton has called it "the black Greenwich Village" (Hunt & Ramon, 2010, p. 119).

Culturally, Leimert Park has an exceptional core - that is simultaneously threatened in the next 5-15 years by projected growth and gentrification (Kaplan, 2013). As a planned community developed in the 1920s, the unique layout of the central plaza provides a perfect venue for festivals, events, and protests (Hunt & Ramon, 2010). But the rich public space of the neighborhood is also ripe for redevelopment plans that come on the coattails of the proposed subway.

Throughout the project, Caldwell invoked fears of a "proposed new subway line, which could drive a real estate rush. Can abandoned phone booths somehow retain our cultural core?" As will turn out to be important, Caldwell is also well networked to business and city leaders. Yet Caldwell was only half the story.

The second half of the project came from a University group. Matching the two groups was a central premise of the project, providing expertise and legitimacy from two poles. As depicted in Figure 4, Caldwell led the first group, aligned with bottom-up planning. The second group, based at the University of Southern California, led the design of technology processes, broadly understood to include not simply the purely technical aspects but also their integration into user practices and interactive experiences.

Altogether, the project involved roughly 30 core participants and a dozen or so peripheral participants. This was a highly diverse group across many dimensions: it included more than 1/3 community participants and slightly less than 2/3 university participants; it was balanced in terms of gender and supported diverse racial and ethnic groups (56% white and 44% non-white, mostly African-American) a remarkably rare feature for technology-related endeavors. Most were in their twenties (67%), although some participants were in their older teens and others over 50. The university participants were mostly graduate students and came predominantly from the Schools of Communication and Cinematic Arts, but included several students, alumni and faculty with training in computer science.

The community participants claimed diverse occupations, including several high school students, a photographer/actress, a community organizer, an electrician, a musician/vegan cook, a filmmaker, a muralist, and hip-hop artists. Peripheral participants were a similarly diverse group whose expertise was sought at specific points in the project. For example, a friend with welding expertise and equipment was roped in to offer a welding workshop when participants needed to fabricate solid bases for the payphones. (Members of both groups share authorship of this paper in the tradition of participatory action research. A full list of participants can be found on the project site at http://leimertphonecompany.net/about-us/ )

Harder than it Looks - Like Oil and Water

Why not a traditional technology process, especially a participatory one? At several points, Leimert stakeholders pushed for the idea of a 'hackathon.'3 These marathon coding events are a recent form of open innovation (Chesbrough, 2003; Seltzer & Mahmoudi, 2013), which pushes firms and governments alike to look outside their institutions to tap the ideas of ordinary customers and open discussion. However, in practice the focus of open innovation has been to recruit raw coding power, ideas or data - not planning. If the goal is engagement and planning, the presumptions of technological literacy in hackathons can make them exclusionary.

The most immediate limitation of tech-centric approaches is the equity of participation. Technological expertise is not evenly distributed. The technological "participation gap" is one key indicator. As Jenkins et al. (2007) have described, concerns over the digital divide are giving way to a gap in participation.

If not traditional technology, what of planning? To tackle the phone booth, Caldwell could have tapped into traditional city-led strategies. For example, he might have tapped into redevelopment projects, which in Los Angeles have largely focused on affordable housing (Public Counsel et al., 2012). Yet partnership with grassroots organizations in "staged participation" is rarely as participatory as proponents claim (Innes & Booher, 2005). Another barrier is that the issue focus of government-led planning often emphasizes basics like affordable housing; by comparison, technology innovation can seem a radical frame in low-income neighborhoods.

The best alternative may be planning as "self-organization," which is more flexible but rarely has resources beyond the time provided by community members. Caldwell was already a key force in organizing bottom-up events, including the regular "Leimert Park Art Walk" that included African masks and takes place monthly in Leimert. Yet technology was distant from all these modes of self-organization. Caldwell had repeatedly struggled to sustain collaborations with technologists. Too often, technology expertise was elusive and polarizing -- something you "had or you didn't." In Leimert, groups either seemed very tech savvy (like Blacks in Tech), or had no technology at all (like the Art Walk). As a result, integration of technology and culture seemed particularly challenging.

Prior attempts in Leimert have separated like oil and water: either technology dominates the conversation (with large gaps in tech literacy, according to our interviews), or else the community resorts to cultural storytelling. In our years of experience, this seems to generalize; with a new bottom-up project, the separation often takes place in the very first meeting when one expertise is established as dominant. The conversation is either dominated by technologists describing "what is possible" in terms of code, or planners describing "what is possible" in terms of entrenched group politics. In other words, this is an epistemological problem that reveals differing practices and ways of problem-solving in the world.

The challenge is thus how to sustain an open conversation in both domains.

APPLYING THE "SOCIAL SCAFFOLDING"

Can a deliberate methodology sustain deep engagement? Engagement may be the central challenge for voluntary participation, but the term is broadly used and often under-theorized for bottom-up design and planning. For inspiration, we draw on the literature of neighborhood effects and civic engagement (Kim & Ball-Rokeach, 2006a; Sampson, 2012). In brief, residents who are locally engaged in neighborhood issues must have a sense of (1) what the neighborhood is - its collective identity, (2) a feeling of being connected to the neighborhood - known as collective belonging, and (3) that their participation will actually make a difference - or what is called collective self-efficacy.

For engagement the act of design is distinctive, since design gives participants something immediate to do. With this power comes some responsibility, since success can build self-efficacy, but failing can undermine it. Low trust and resiliency is a recurrent problem in many historically marginalized neighborhoods, and net disengagement with a neighborhood is possible, if the design process is not structured carefully. The core problem we identify is that the process for design and planning often fails to deliberately build belonging and efficacy, and thus is limited for engagement - especially for sustainable planning.

This study defined a design methodology of "social scaffolding" in four parts. The 'scaffolding' refers to our goal of helping the group to perform beyond their immediate reach.4 In brief, the scaffolds are to:

- Sustain a Participatory Culture. Support a process that is playful and insistently open, feeding off the neighborhood's cultural practices. Specifically, we echo the criteria outlined for participatory culture by Jenkins et al. (2007), including low barriers to participation and ensuring that all contributions are appropriately valued.

- Deepen a Neighborhood Story. The neighborhood identity has implications for economic development and civic engagement. Rather than presume to invent the grand narrative or avoid it, find a way to retell it. Begin by identifying the cultural assets that make the neighborhood distinct. Especially for historically marginalized neighborhoods, telling the story of "who we are" gives power and roles for local voices that lack elite technology skills.

- Mix Technologies of Old and New. Frame the desired product as larger than any single technology, yet cheaper and more obvious than we might expect. For example, consider the role of "paper as mobile media." Low-tech and low-cost shifts the conversation to planning the social side of socio-technical systems, and helps to build technology skills and confidence in design participants.

- Rotate Institutions. A central practice of planning is to look beyond the most immediate users to consider all stakeholder groups, including non-users. Power relations between groups are at the heart of sustainability and equity concerns. To resist calcifying at one power hub, deliberately rotate the physical site of design, and recruit a rotating cast of institutional figures.

The Scaffolding in Action

In brief: after 14 payphones were purchased on eBay for a mere $309 USD in total, an intensive design process began. To balance the university and community, weekly meetings in early 2013 included one at a local university, alternating with one at a community hub for culture. Groups formed to build coherence by creating specific design plans. Most of the design took place in a single five-week window. Throughout, facilitators structured the groups' activities to build a shared knowledge base, including some basics of welding, rapid prototyping, local music and arts culture, and Python programming for Raspberry Pis. The three design plans that emerged were validated at a community "pitch-fest" to build stakeholder support, raise funds, and build a public constituency in support of the proposed technology.

The productive drama and details of this process are described below, illustrating how the social scaffolding functioned in the Leimert Park case.

Sustaining a Participatory Culture

In Leimert the facilitators sought to sustain a process that would outlast a single technology, and thus cultivated a broader set of behaviors and social practices. We parallel Jenkins' description of participatory culture (Delwiche & Henderson, 2012; Jenkins et al., 2007), as a useful frame for the essential elements, including having low barriers to entry/expression, supports for sharing one's creations, mentorship, and some degree of social connection, where members believe that their contributions will be valued. Importantly, these features were echoed in face-to-face outreach, not just open-source code repositories. An "open door" was literally propped at KAOS Networks for strangers to wander in off the street, with food circulating and music and often African drums being played in the design space. These practices also contrasted with traditional planning, with its end-driven process to achieve a narrow result.

The role for "friends of the project" provides a good illustration of the participatory culture, in contrast to the more instrumental approaches typical in city planning and technology design. The "friends" had episodic involvement yet were still considered members, echoing the legitimate peripheral participation (Lave & Wenger, 1991) that underscores communities of practice. Just as importantly, the contributions of peripheral members were diversely valued, as opposed to many technology projects where the 'openness' is restricted to open-source code. Contributions from the "friends of the project" ranged from hiphop artists who contributed rhymes, to celebrity judges who agreed to comment on the three prototype designs, shop-owners who played a cameo role in prototype videos, local merchants who supplied food and drinks for design sessions, and even an artist who taught welding skills on the phone base. Broad peripheral participation created a network of supporters who remain engaged with the project and could be mobilized to build support and neighborhood legitimacy, with on-going loose ties to the more regular participants.

Seeking to start a participatory culture from scratch is dangerously presumptive, especially given the power dynamics of historically marginalized communities like Leimert. Instead, we sought to tap existing cultural momentum in hopes of sustaining participatory practices. In Leimert Park culture momentum was particularly strong around music, going back to the historic figures mentioned above such as Ella Fitzgerald. The scene remains vibrant: within the last 20 years the hiphop community has involved notable artists such as Jurassic 5 and Abstract Rude. Collaborations emerged most prominently through a monthly workshop called "Bananas/Project Blowed" that asserts it is the longest running open-mic hiphop event in the world.

Occupying the physical space of Project Blowed was valuable to set the design culture for the payphone project. Whenever technology literacy seemed daunting, KAOS leaders would remind everyone that the success of hiphop also depends on remix, repurposing, and appropriating technology. Energy was kept high by fieldtrips late at night to hiphop freestyle sessions. Artists were aggressively recruited. By legitimizing technology in terms of culture, we resisted the temptation to cede leadership to technologists. Everyone was invited to participate, and to legitimize a range of complementary expertise. Maintaining such cognitive diversity (Page, 2008) is essential for addressing the wicked problems at the heart of most social issues and urban planning.

One key innovation was to iteratively create media, especially videos, which told the story of production alongside the evolving group vision. Almost every meeting concluded with a set of deliverables and design teams reporting back to the larger group. These deliverables took the form of design mockups, asset charts, performances, and videos. The design fiction or "scenario" videos sought to succinctly portray how each team's design would function in public space.

Early sessions would spur groups to actually perform as the payphone (Figure 5), alongside traditional users and more passive bystanders. Drama prototyping has previously been applied effectively for prototyping urban furniture, including augmented swingsets for children and large public screens (Rubegni, Memarovic, & Langheinrich, 2012). In Leimert, the performances helped to concretize weekly deliverables and work out an embodied sense of what the social relations around the payphones might look like.

Taking the performances further, teams also came up with more polished design fiction videos called "scenarios". Scenarios provide a compressed means for presenting short stories about the use of technological designs, contextualized within their setting (Iacucci & Kuutti, 2002). Much like the drama prototyping, scenarios were a way to concretize multiple design concepts into an elegant example of the total user experience. In video form, scenario prototypes allowed teams to create speculative evidence of how their design would function, similar to planning proposals.

The videos help to sustain the participatory culture through distribution. Key videos were published online, cross-posted to social media, and promoted in weekly email summaries. In other words, there was a deliberate social media strategy -- beyond project management -- to actively tell the story of production, and feed the participatory culture.

Deepening a Neighborhood Story

"I think what we're missing... is a narrative. People can't find meaning out of Leimert Park anymore." - C.Z. Wilson, local business owner

For many technologists, the "neighborhood story" may be a surprising scaffold. Yet the concept is powerful, first to shift the technology frame, and then to prioritize local assets in the design process. Perhaps most surprising, the neighborhood story also has implications for local economic development and increased civic engagement.

Neighborhood stories are simple narratives of "who we are, and why we are distinct."5 But there is a deep shift for technology design that comes with prioritizing the neighborhood story. Most importantly for process, the neighborhood story shifts attention beyond technologies that serve individuals, to consider technologies of the community. How?

Consider one design group, conveniently nicknamed "Transmedia Storytelling." This group wanted to redesign the payphone as a storytelling hub, where participants could record a personal narrative or hear a curated tale. Cultivating a neighborhood-level story was initially a simple content filter, restricting the instructions to recruit stories about the community's origins, values and future. Yet the team soon realized that deeper engagement mechanics were also possible; for example, the payphone could structure a scavenger hunt, sending visitors from payphone-based clues into local businesses, gathering interviews and trading stories. Such experiential challenges were harder to design - and fundamentally different in effect since they would build active social capital between residents (echoing the linking of Gómez, 2013). Their target is the social fabric of the community.

Seeking neighborhood stories helped to keep the focus on the immediate local community. To tell the neighborhood story, the physical geography, architecture and community history are all key actors in the tale. So are local events. Half the design sessions took place across from the central park of the neighborhood with its drum circles and weekly African-American street fairs -- but also a highly visible homeless population. Looking for the neighborhood story regularly pulled designs to consider interfacing with the park and its inhabitants.

For the design process, neighborhood stories were pursued by tapping into the 'cultural assets' of the location. For example, during one design meeting at the community location, teams traveled around a three- or four-block radius to identify the assets of the neighborhood. The approach draws on asset-based community development (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993), which aligns with bottom-up planning. Both local community members and academic members explored the streets and took photos or short videos of things that stood out to them because of social, aesthetic, or cultural significance. When captured in group stories, the assets were connected to the concerns of the anticipated audience, all tied to the same geographic space. The approach thus maintained an emphasis on the situated knowledge (Light, Egglestone, Wakeford, & Rogers, 2011) of the community, in contrast to technologies that define neighborhood simply in terms of geo-coordinates.

One of the designs particularly embodied the neighborhood story. The "Dial-A-Track" group envisioned a novel form of distributing local music through the payphone. A number of the group participants were musicians already tied to the "Bananas" hip-hop events. Their motivation for participating was often highly personal. For example, one participant emphasized that he needed to "sustain my finances through art...so I have to find new ways to be innovative." He feared his music was getting lost on the globally-flat internet. By participating in the design process, this young man hoped to better distribute his own music, and simultaneously deepen its ties to the physical neighborhood.

Slowly, the music team found ties to local assets. They ultimately conceptualized a way to create (1) a listening booth to preview local artists' music, and (2) sell tickets to local hip-hop events in the neighborhood. (See also their pitch video.) Then they pushed to embody the neighborhood story, using the payphone to create relationships. They proposed to use the phone to play music through large speakers, creating spontaneous events to spark conversation or dancing.

Before the technical code was ready, the group tested the payphone as a public site for performance. At a "Bananas" performance, the group set up a microphone and speaker in front of the broken KAOS payphone. With great enthusiasm, rappers began joining in a circle and freestyling about the payphone and the associations that it conjured. People passing by were so intrigued that they decided to stick around and watch the show or contribute a few lines rapping about the payphone. The success of that night led the group to release a "Rap the Phone" video online shortly afterward.

Debate about the "Rap the Phone" video also revealed cultural fault lines that were an implicit sign of success. Specifically, one older participant warned that blasting hip-hop would annoy the old-timers, and urged the group to restrict payphone-amplified music to the jazz of famous (deceased) residents. A debate ensued about editorial policies in public space, similar problems with the drum circle in the park, and whether technology could ease friction in the selection process. Of course, collective identity is contested in any community, and neighborhoods themselves are fundamentally imagined - just like nation states (Anderson, 1983). Strong neighborhoods have powerful identities, and in their name residents can take collective action. The implicit success of the debates in Leimert is that the terms of the debate around the neighborhood identity aligned with community planning, with its contestations over "who we are" - and where to go next.

Greater civic engagement is an implicit reason to deepen neighborhood storytelling. For bottom-up planning, voluntary engagement is a prerequisite to any action. Research on neighborhood storytelling has shown that civic engagement is associated with strong networks that tell neighborhood stories - including local media, residents in face-to-face conversation, and community-based organizations (Kim & Ball-Rokeach, 2006a). Several of these dimensions are included in designs like Dial-A-Track, including catalyzing interpersonal conversation in public space and connecting to neighborhood organizations. The third dimension, local media, appeared quickly during the design process, with coverage of the design appearing in the Los Angeles Times as well as even more hyper-local outlets like Intersections South LA and KCET Departures (see the project's summary of news coverage).

Economics - a central driver of urban planning - is a final reason to focus on the neighborhood story. As part of the creative economy (Florida, 2007), art clusters like Leimert Park have a particular role in recruiting talent, despite the risks of gentrification. For Leimert, the arts are known but the connection to technology appears to be missing. From our interviews, several business owners and technologists expressed concern that talented African-American youth had nowhere locally to take their technology skills and passions, and so they were leaving in droves, taking their talent with them. In search of strategies, funders like the National Endowment for the Arts are increasing support for "creative placemaking" grants (Nicodemus, 2013). Yet few such placemaking strategies address technology. To bridge innovation with placemaking, the neighborhood story provides a promising scaffold for broader use.

Mixing Technologies of Old and New

The third scaffold redefines "good technology" as a literal mix of old and new. Gaps in technology expertise are a major concern for planning any public technology. Technological divides mean that planners cannot meaningfully involve community members or team partners in significant collaboration, and are thus often forced to relegate technology to experts. Even in community-based solutions, some technological literacy is needed in order to maximize the potential of group members in the design process.

Combinations of old and new can help shift to the social side of socio-technical systems. Without an explicit focus on the old, the new can easily take over.6 We find that an archeological approach proves useful, alongside low-cost technologies of the present. For example, hulking payphones can now fit an entire Raspberry Pi computer inside (as per Figure 6). To embrace the old, we also draw on design strategies of appropriation, creolization, and even cannibalism (Bar, Pisani, & Weber, 2007; Schiavo, Rodríguez, & Vera, 2013). Moving indirectly and iteratively can be an important approach for deepening technology literacy.

In Leimert, the archeological approach was inspired by the physical presence of the 14 ancient payphones from eBay. Participants wondered: what could be inside? The phones' cost was low, creating a buffer for mistakes and fostering openness to experimentation. One group of participants catalogued the contents of several phones (see Figure 7), investigating old technology in order to gain fresh eyes.

Focusing on low-cost and low-tech can also help to resist the high-tech lure. Very simple pervasive technologies can be embedded in the neighborhood. For example, printed QR codes on store windows can reveal and structure participation in a business network beyond the street grid. In this way, paper can be a core technology to structure neighborhood activity. Therefore, all groups were encouraged to attempt paper prototypes and to consider paper as a genuine component of their design.

Ironically, the very passiveness and non-interactivity of low-tech solutions like paper can help align with planning, where non-users are a more central concern. Furthermore, most users of neighborhood technologies prefer to initially observe and consume, rather than directly use or contribute (Saad-Sulonen, 2005). As one group discovered with "Rap the Phone", the physical footprint of the phone booth in the neighborhood can support and legitimize peripheral participation, unlike peering over someone's shoulder at a mobile phone screen.

Our hacking process thus involved dismantling the phone to understand its constituent parts, then establishing an inventory of all the "triggers" we would be able to use in re-purposing its functions: twelve keypad buttons, one switch detecting whether the handset is on- or off-hook, the coin-sorting mechanism detecting what coin has been inserted (and rejecting foreign coins or slugs). We then set out to detect these triggers and pass that information on to the RaspberryPi. This turned out to be more complex than anticipated, as the phone triggers are analog and the Pi expects digital inputs. We ended up designing a simple circuit to allow the RaspberryPi to detect keypad entry and coin drops on the payphone, which we later could have manufactured as a printed circuit board.

The software portion of the technical system was then comparatively straightforward. We wrote simple python scripts running on the RaspberryPi, instructing the Pi to perform certain actions when a particular trigger is detected: these are variants on simple logic such as "when the handset is picked up, play the welcome message sound file which instructs people to press buttons"; "when a press on keypad number three is detected, play this music file". The possibilities are quite wide ranging, since we can detect multiple trigger sequences (e.g. someone playing 'chords' on the keypad) and instruct the Raspberry Pi to perform a variety of actions (e.g. play videos, connect to the internet, send a social media message, etc.). At this point however, we have only scratched the surface of these possibilities. We hope soon to release the open-sourced specifications of our "Piphone" kit and encourage others to experiment.7

Mixing old with new technology helped to sustain a longer conversation about the right approach. Going further to echo agonistic design, there may be particular value for marginalized groups in supporting a plurality of ideas throughout the process (Björgvinsson et al., 2012), resisting the temptation to seek consensus. Multiple solutions were encouraged by how the three payphone design groups were configured (each with a mix of university and community members). Pockets of expertise were encouraged, echoing the 'lego approach' of Heaton and colleagues (2013). Resisting convergence on a single design helped to build trust between stakeholders, and develop a conversation about what the neighborhood could be. Old technologies help to invoke the neighborhood's past, and build sensitivity to older residents.

Aging payphones also raise questions of evolving infrastructure. Considering a payphone network (beyond any one phone) aligns with the urban planning emphasis on public infrastructure and public goods. In Leimert, we found that some of the more innovative ideas emerged from alternating between the levels of single prototype and infrastructure. For example, talk of public infrastructure in Leimert turned quickly to public libraries and homeless shelters - and how a payphone could give directions, or extend information services onto the street. The approach aligns with a design strategy called 'infrastructuring' (Björgvinsson et al., 2012), where the old and new are more continuously integrated.8

Rotating Institutions

A central concern for planning is to secure cooperation from local stakeholder groups. Such consideration is far beyond participatory design, which traditionally emphasizes binary power relations in a workplace. Even community-based participatory design (DiSalvo et al., 2013) typically has an inward focus. By contrast, planning with neighborhoods like Leimert Park only makes sense from a broader view: in relation to other Los Angeles neighborhoods - and key institutions. One scaffolding approach is to deliberately alternate design activities between a community organization and the university, and to recruit other stakeholders throughout the process.

The most problematic stakeholder in the payphone design process was probably the University of Southern California. In multiple interviews, community members expressed fear that the University would "steal" the payphone idea and profit from it. Such concerns go beyond the privileging of academic knowledge identified by Light, Egglestone, Wakeford and Rogers (2011). To answer profit concerns in the short term, the group made most intellectual property open, and shared any copyright with the community partner (KAOS Networks). In addition, the University itself has a complicated relationship with the under-privileged neighborhood that surrounds it. While the University offers much support to nearby schools and communities organizations under its "Good Neighbor" program, it has also been building a fence around its campus and advises students during orientation against venturing in the surrounding neighborhood, depicted as dangerous. All in all, this creates challenging conditions for collaboration.

However, to take seriously the longer-term concerns of urban planning, we recognized that trust is often best built in person (not just through legal agreements). Rather than picking one site for design, the payphone team developed a strategy of alternating between the University of Southern California (USC) and the community site (a 10 minute drive away). The goal was to build the network relations and social capital that could only be done at that site. So on Wednesdays, when the full group gathered at USC, special effort was made to invite Deans who might have a personal interest, such as in African-American culture. And on Saturdays, when the full group was at KAOS Networks, special effort was made to invite key local residents such as business owners.

Recruiting input from stakeholders also made the process function more like planning, with unexpected benefits for design. For example, in Leimert the group invited Brenda Shockley, a key member of the local Business Improvement District (BID). The BID is the focal point for business interests in the area. Brenda challenged the group to see if payphones could create greater foot traffic to local businesses. One group investigated, taking their design to art galleries and calling themselves the "Art Buzz".

The "Art Buzz" group tapped the BID network, focusing on the owner of one local art gallery in particular. The gallery became the grounding focus for their design scenario video (see Figure 8). The video was shot on location in the gallery and helped to further concretize the direct effects of the phone on the local community and its economy.

At the end of the initial design period, the networks were joined in person at one site for a community "pitch-fest." Each team took to the stage of KAOS Networks, with a prominently displayed phonebooth - including a number of newly embedded technologies. Yet the emphasis was on their design videos as a kind of community plan for the technology, seeking further input. Veteran judges were recruited, but less on traditional academic expertise than on their role in relation to stakeholder groups: one was a leader in the nonprofit sector, another a local business person, and a third was a USC professor. Naturally they had other personal identities as well, often intersecting with the neighborhood itself. Yet their public statements felt curiously like testimony at a public hearing, demanding quality for the future of Leimert.

The recommendations of the judges ultimately returned to the neighborhood story, serving as a kind of validation for the design approach. Two of the three emphasized in their remarks that the neighborhood especially needed a narrative to capture its evolving identity - a way to connect its famous past to a sustainable future. Certainly they liked the municipal wifi, but they also wanted to know how the payphone could deliver a story tied to economic returns - an equivalent to the story of "Silicon Valley" and its tech clusters, or the "Napa wine region" with its bottled brand.

IMPLICATIONS AND REFLECTIONS

Modern neighborhoods are hybrids, emerging from the planning of physical space and increasingly digital layers of mediated communication (Gordon & de Souza e Silva, 2011). Yet prior research on participatory planning has been relatively isolated from work on participatory design (e.g., in e-planning per Saad-Sulonen, 2013). Current social models, including civic hackathons and community planning meetings, tend to privilege one kind of expertise at a time, at best designing a technology to address a community issue. The process rarely combines the user-centered methods of designing technology with planning's explicit processes of community-centered negotiation.

This study proposes a novel approach to combining planning with participatory technology design. We argue that not all technologies are suitable, nor all kinds of planning. In particular, we bring specificity to the call of Gurstein (2007) for community informatics to appropriate existing technology, as well as the 'infrastructuring' of Björgvinsson et al. (2012). In particular, this study contributes to the literature on participatory planning by defining a legitimate area of overlap: designs that seek to be "socially embedded" in physical space, building community coherence (Kim & Ball-Rokeach, 2006a) through a process of "deep engagement" in both planning and design. The central challenge is not technical but how to sustain the social scaffolding, especially for underserved neighborhoods with low levels of technology literacy.

Process and Outcome Summary

The process in Leimert was galvanized by making something - half prototype, half community plan. At first glance, traditional technologists might be disappointed that there was no immediate software launch (although a very real product is under construction). Likewise, planners might miss a written plan with established indicators. But for our framework, neither is the immediate goal.

Instead, our framework reveals the importance of a process that builds the neighborhood capacity to plan for local technology, and to foster the social capital, sense of belonging and efficacy that lead to civic engagement for the long term (Kim & Ball-Rokeach, 2006b). Several indicators stood out. For example, participants had a greatly increased capacity around what we have come to call 'payphone politics' - like identifying the hidden power relations and functions of payphones, and involving diverse constituents in reflecting on the feasibility of change.

Our methodology brings technology design more deeply into the established phases of participatory planning. Traditionally, information and communication technologies are invoked in the "expressive" phase of participatory planning (Horelli, 2002; Saad-Sulonen & Horelli, 2010). (The full process outlined by Horelli begins with a diagnostic phase, then expressive, conceptual, organizational and finally political phases.) Certainly much of the payphone work was solidly in the expressive phase. Yet the Leimert case is also profoundly diagnostic, helping to identify community priorities and planning opportunities. Just as importantly, the Leimert case also extends to the political, since the process was carefully structured to build community support and raise funds for investment in one or more of the prototypes.

In brief, the phases for the proposed model can be summarized as: (1) diagnosing a public technology, especially one that is broken or not focused on the local community; (2) expressing possible solutions as plans and technologies by embodying them; (3) politically articulating the socio-technical designs to local stakeholders and organizations; (4) if political will and funding can be secured, then implementing the plan/technology through further participatory design.

We should not of course underplay the importance of delivering something in the early phases - it is indeed important for both community and academic participants to have something to show for their efforts (if only for the efficacy measures tied to community empowerment). What that product is, however, should not be overly constrained since the goal is to build a responsive capacity through a portfolio of products, not a consensus design. The importance of agonistic design (Björgvinsson et al., 2012) becomes increasingly important as design shifts toward planning, since technologies in public space structure participation, and diverse communities have varied modes of participation.

Methodologically, the "social scaffolding" provides a deliberate recipe to sustain deep engagement. Each of the four steps is a useful constraint, narrowing the kind of technology design to be compatible with bottom-up planning, and vice-versa. The first step is to invite participation in a participatory culture, including low barriers to entry and recognition for meaningful contributions - whether as code or a video. More radical for technologists is the call to deepen a neighborhood story, using local culture to tell the story of "who we are," and to build the collective brand. Thus one theoretical contribution of this paper is to introduce and demonstrate neighborhood storytelling (Kim & Ball-Rokeach, 2006a) as a framework to bridge participatory planning with informatics and technology design.

In terms of mixing technologies of old and new, this study finds that it is productive to focus on re-inventing existing urban objects. They are public, familiar, yet obsolete and neglected. Bringing them back to a second life creates surprise and wonder, inviting people more broadly to re-examine other features of their neighborhood which they were taking for granted. In particular, we do not claim that the object itself is a profound innovation. But rather the process of its archeology and rebuilding, its placement in public space, and the conversation across generations all bring new and more honest eyes to recent technologies. Thus the shift toward planning benefits from modes of participatory design that emphasize appropriation (e.g., Bar et al., 2007).

By rotating institutions, we shift the focus slightly away from the hot contentious issues, and offer a less confrontational, more whimsical opening for community conversation. Through alternating between physical sites, each place can bring its own authentic networks. Inviting stakeholders into physical space, and paying attention to their ideas, can build trust. This takes time, and in the case of university-community relations the horizon is often long indeed. But eventually the process should allow people to build common ground that will in turn prove useful when confronting the really contentious issues; this would be useful grounds for future research. Theoretically, this finding contributes to the literature on community informatics by showing how the turn toward planning necessitates going beyond user-centered design to additionally adopt the organization-centered approaches used in planning.

Our process served as a platform for planning, with social scaffolding to sustain interest in a public technology and articulate the community stakes. Prior to the process, there was little understanding of payphone politics. Rather than deliver a design "solution," the process sustained a provocation that invited residents and passers-by to re-examine neighborhood characteristics and priorities. The design process was thus a new way to reflect on public space in terms of technology, sustaining planning conversations among people who would otherwise not engage with technology design.

Perhaps the best indicator for deep engagement across fields is shared language. Building common language is an important component of participatory development and systems design (Dearden & Rizvi, 2008). Media outlets like the LA Times also played a role in sustaining the conversation, internally and with stakeholders. Specifically, media attention helped legitimize this community project in the eyes of neighborhood organizations, even as it provided respectability within the University for our unconventional work with unusual technologies. While the kick-off project was completed after just a few months, culminating in a public unveiling of three prototypes in late spring, a core subset of the group remains involved. Six members of the group traveled to Detroit several months after the pitch-fest to share the approach, and urge other cities to consider payphone localization. We have since completed a physical design, dubbed "Sankofa RED", launched in December 2013 (see Figure 9).

Broader Implications

The future of local communities may depend on their ability to plan their own technology, including payphones. Deep engagement may be necessary to sustain a conversation across the disciplines of participatory planning and technology design. Our framework provides a methodology to help situate engagement in physical streets, living communities and local networks. For planning, the approach helps tackle a specific set of local planning issues, especially around localizing technology and understanding the planning of complex socio-technical systems.

Rather than simply consulting residents (i.e., those who live in Leimert), the proposed process provides an entry point for a diaspora of stakeholders who are investing in the community. Legitimizing the peripheral participation of 'friends of Leimert' as loose ties and through sporadic participation was an important bridge from traditional technology design toward participatory planning. In a small way, the project helps to shift the basis for civic engagement around technology toward modes of community planning, adding the voices of stakeholders to those of explicit users, toward planning communities in story and code.

ENDNOTES

1A decline over the decade leading to 2009

showed payphones dropping from 2.1 to 0.5 million,

including independent operators (Trends in Telephone

Service, 2010); this is the last year the report was

issued by the US Federal Communications Commission.

2 See LA Times neighborhood profile at

http://maps.latimes.com/neighborhoods/neighborhood/leimert-park/

3In fact, as part of the White House national

day of "civic hacking," community partner KAOS Network

hosted a discussion of hacking tactics for the project.

See

http://leimertphonecompany.net/day-of-civic-hacking/

4Scaffolding is a term borrowed from the

learning sciences, including an explanation for how

technology can "scaffold" tasks to empower learners

beyond their independent ability. For an overview of the

rich debates that give substance to scaffolding as a

metaphor for collective work and informal learning, see

Pea (2004).

5Neighborhood stories are essential to the

collective identity. Strong neighborhoods go beyond their

geography; they are place-based communities - products of

human history and the cultural imagination, "imagined

into being" much like nation states (Anderson, 1983).

6For example, New York City held a payphone

redesign competition in 2013, with a decidedly high-tech

winner that included a 10-foot-tall double-sided

touchscreen.

7Team members Andrew Schrock and Sabelo

Mhlambi led much of the development of the circuit board

and Piphone Kit. For details, see

http://leimertphonecompany.net/PiPhone/

8Infrastructuring contrasts with the more

fixed nature of 'infrastructure' as a mechanical

substrate for building upon; The process of

'infrastructuring' emphasizes the ongoing aligning of

networks - not of things, but working relations - across

stakeholder groups and across socio-technical contexts.